|

Artículos Work Key:

|

Silvia Pellegrini1

Daniela Grassau2

1 orcid.org/0000-0002-9892-2614. Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Chile. spellegrini@uc.cl

2 orcid.org/0000-0001-7846-8322. Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Chile. dgrassau@uc.cl

Recibido: 2017-08-28

Enviado a pares: 2017-10-09

Aprobado por pares: 2017-10-30

Aceptado: 2017-12-13

Para citar este artículo / to reference this article / para citar este artigo: Pellegrini, S., & Grassau, D. (2018). Work key: A theoretical-technological path to organize the hidden components of communication. Palabra Clave, 21(4), 1050-1074. doi: 10.5294/pacla.2018.21.4.5

Abstract

This article presents the theoretical bases and the research process that supported the creation of a technological tool to manage daily work in the world of communications and to increase the quality of its products. A Chilean team investigated the role of communications in the strategic, journalistic and audiovisual areas. The goal was to identify its processes, actors, relationships, environment variables and relevant performance indicators and to develop a common theoretical-conceptual framework with relevant quality indicators for evaluation and improvement. The main result of the research is a platform, Work Key, with separate components for the three areas. It also considers that each professional can “take their office with them,” thanks to synergistic components designed for smartphones and tablets. Its conclusions tend to contribute and establish interesting nuances in a discussion regarding the impact of technological changes and to supply new tools to face current difficulties in the communicative process.

Keywords: Communications; platform; corporate communication; journalism and audiovisual production (Source: Unesco Thesaurus).

Resumen

Este artículo da a conocer las bases teóricas y el proceso de investigación que respaldó la creación de una herramienta tecnológica destinada a administrar el trabajo diario en el mundo de las comunicaciones y a aumentar la calidad de sus productos. Un equipo chileno investigó la función de las comunicaciones en las áreas estratégica, periodística y audiovisual. El objetivo fue identificar sus procesos, actores, relaciones, variables de entorno e indicadores de desempeño relevantes y desarrollar un marco teórico-conceptual común con indicadores de calidad relevantes para su evaluación y mejoramiento. El principal resultado de la investigación es una plataforma, Work Key, con componentes separados para las tres áreas. Considera también que cada profesional pueda “llevar consigo el escritorio” mediante componentes sinérgicos pensados para smartphones y tabletas. Sus conclusiones intentan contribuir al establecimiento de matices relevantes en la discusión actual sobre los cambios tecnológicos, y entregar nuevas herramientas para enfrentar las actuales dificultades del proceso comunicativo.

Palabras clave: Comunicaciones, plataforma, comunicación corporativa, periodismo y producción audiovisual (Fuente: Tesauro de la Unesco).

Resumo

Este artigo torna públicos as bases teóricas e o processo de pesquisa que apoiaram a criação de uma ferramenta tecnológica destinada a administrar o trabalho diário no mundo das comunicações e a aumentar a qualidade de seus produtos. Uma equipe chilena pesquisou a função das comunicações nas áreas estratégica, jornalística e audiovisual. O objetivo foi identificar seus processos, atores, relações, variáveis de contexto e indicadores de desempenho relevantes, e desenvolver um referencial teórico-conceitual comum com indicadores de qualidade relevantes para sua avaliação e aperfeiçoamento. O principal resultado da pesquisa é uma plataforma, a Work Key, com componentes separados para as três áreas. Considera-se também que cada profissional pode “levar consigo seu ambiente de trabalho” mediante componentes sinergéticos pensados para smartphones e tablets. Suas conclusões pretendem contribuir para estabelecer matizes relevantes na discussão atual sobre as mudanças tecnológicas e oferecer novas ferramentas para enfrentar as atuais dificuldades do processo comunicativo.

Palavras-chave: Comunicações; plataforma de comunicação corporativa; jornalismo e produção audiovisual (Fonte: Tesauro da Unesco).

Introduction

The significant changes that are experienced in today’s culture, such as the expansion of personal and social freedoms, increased nuances in judgments and understanding of the reality that surrounds us, as well as the ever closer ties of belonging and construction of the community, derive significant challenges for communication, with which society has an active synergy: It not only modifies it culturally, but also influences it directly. The awareness of this reality has generated a higher demand for specialized knowledge, strategic diagnosis skills, and the design of professional solutions.

However, certain communication processes continue to be carried out in a practically artisanal way, something that many communicators—even in highly industrialized contexts, and knowing that the quality of products can strongly vary due to this way of conducting them—consider inherent to these processes.

In addition, certain communication processes would highly benefit from using technological skills that are currently in disuse; this would allow the members of a team to work independently but also coordinately, to generate more contacts with different stakeholders, as well as to improve the general quality of its products.

The research team was aware that applying structuring methodologies to communication—a process full of nuances and subtleties—might be reductionist, so the solution proposed aims to organize the elements of decision and production without affecting the creativity underlying the process.1

Hypothesis and Objectives

In Chile there is a lack of systematization of communication-making processes and scarce methodical recording of its intermediate stages by the media, the audiovisual industry (particularly the independent) and by corporate communication agencies. This reality seems comparable to that of several countries, at least in Latin America, and even though they have strong similarities, journalism, the audiovisual industry, and strategic communication present different realities and challenges.

In journalism, for instance, there is little systematization and monitoring of the activities involved in the development of a news story. The generation of news story lists and reports depends solely on the skills of the people who execute them and who rarely have tools to support them to verify the completion of their stages or to measure the quality of the products.

Audiovisual production, on the other hand, requires systematizing an efficient management of available resources in order to comply with deadlines and budgets, among other things.

In strategic communication, the team detected no only a low degree of systematization but an almost exclusive dependency on the talents and procedures of those responsible, without any defined or recognizable process. This implies, in other words, inefficient lines of communication, unidentified processes, and excessive dependence on the organizational memory of those responsible. Thus, management of corporate communications continues to focus on operational aspects with little technological support, which weakens its strategic nature.

Considering the above, the research team decided to delve further into these processes, recognize them and describe them in order to find their common elements and their interrelationships, so as to develop an ad hoc working tool that supports the development of strategies and the management of information in all three fields. The resulting platform represents a technological solution that could be used independently in corporate communication, news story budget and the production of an audiovisual fictional or non-fictional creation, under a unique conceptual scheme and in a collaborative and expeditious way.

Background

Although the idea of establishing a common framework in the administration of certain aspects of communications is recent, there is literature that allows a glimpse into its main elements in corporate communication, audiovisual production, and journalism.

Corporate communications—or strategic communications or corporate affairs (Tironi & Cavallo, 2003; Argenti, 2009)—, are in charge of managing a harmonious relationship with stakeholders, that is, “those groups without whose support the organization would cease to exist” (Freeman & Reed, 1983, p. 89), a need that is increasingly recognized (Argenti, 2009; Calderón, 2011; Porter & Kramer, 2011; Tironi & Cavallo, 2003; Van Riel & Fombrun, 2007; Villafañe, 2013; Fleisher & Bensoussan, 2007). This exceeds the traditional concept of public relations, insofar as the challenge is not to send messages to a passive receiver, but a two-way exchange with a proactive partner (Argenti, 2009; Van Riel & Fombrun, 2007; Grunig & Hunt, 2000). This vision has enabled communications to reach the status of a strategic management tool, which includes monitoring the environment—that is, listening and analyzing possible partners and anticipating its consequences (Van Riel & Fombrun, 2007; Pellegrini, 2015).

Gaining the support of interest groups becomes an essential element of the corporate strategy, but it is not possible to do it mechanically; appreciation or reputation is built through what businesses say (the least credible source), what they do (which often contradicts the corporate speech, undermining its credibility), and what others say (the less controllable factor). Technological supports may contribute to the systematic management of the three aspects.

Audiovisual production can lead to products or commercial goods, public and private, tangible and intangible (Stanton, Etzel, & Walker, 2007; Soto, 2015). Each project establishes a production process with unique features. Audiovisual production involves the coordination of the financial, technical and human elements that will participate in the development of the project (Celery, 2001), but it has a central figure: the producer, who acts as the administrator, ensuring the correct management of time and financial resources (Soto, 2013; Worthington, 2009). Its work is usually divided in two roles: a) the executive producer, who is the head of production, with a greater decision-making power (Sainz, 2014) and who has the last word (Jacoste-Quesada, 2004) and is responsible for funding, hiring equipment, marketing and distributing the product (Celery, 2001); and b) the general producer, the right hand to the executive producer, who must comply with the filming plan, coordinate the human and technical team, and stick to the budget (Celery, 2001). The coordination of the communication work aims to keep constant track of three fundamental stages: pre-production (budget, equipment and services, locations, etc.); production (creative proposal and filming); and post-production (editing and sound) (Cabezón & Gómez-Urdá, 2003; Worthington, 2009).

Finally, journalists and newsrooms have followed well-known practices in news production (Becker & Vlad, 2009), with significant impact on their stories and editorial decisions. Editors select and prioritize, deciding the relevance of stories for their audiences. They coordinate journalists in their search, proposition and production of stories, establishing frames and focus. The stories and sources changes while journalists are working and the selection of stories to be published depend on personal experiences and insights, making this a complex task (Puente, Edwards & Delpiano, 2014). Technology can support continuous communications and work between editors and journalists with tools designed for these tasks (Boczkowski, 2004; Pavlik, 2000). First, journalist teams need to coordinate (Puente, Edwards & Delpiano, 2014; Lamelas-López, Pont-Sorribes, & Alsius, 2016) in areas such as which story to select, how to set the agenda, which suggestions to consider, and which sources to investigate (Pellegrini et al., 2009; Pellegrini et al., 2011; Bernal-Triviño, 2015). Since most of the interactions between editors and reporters are based on informal conversations, useful information is not always traceable to improve research and procedures. A tool that provides updated information and tracks could help them do so. Another issue is sharing work with remote colleagues, as in a newscast made by reporters in different cities. Due to the impossibility of a meeting, editors are generally responsible of coordinating reporters, concentrating all flow of information, and thus becoming the bottleneck of decisions and knowledge. Furthermore, relevance is a key factor in news production (Harcup & O’Neill, 2001; Rudat, Buder, & Hesse, 2014) that will determine the final publishing decisions. All of these are tools that help to recognize that relevant stories can improve quality and increase audiences, thus saving time and resources (Puente, Edwards, & Delpiano, 2014).

Even though industry and technology have provided multiple solutions to support communications performance, there are few tools specialized for the early stages of production, and many of them work without interoperability, like social media (Diakopoulos, De Choudhury, & Naaman, 2012; Poell & Borra, 2012; Westerman, Spence, & Van Der Heide, 2014), news media agencies, web-based search engines (Carlson, 2007), and networking (Harcup, 2015). However, technological tools are still not well articulated, as happens, for instance, with software, to produce stories in specific formats (Briggs, 2012; Gillmor, 2006; Bradshaw & Rohumaa, 2013), video and sound edition tools, paper layout, blogs platforms (Briggs, 2012; Chung et al., 2007), and content manager systems (like Wordpress or Joomla) (Thurman, 2008; Du & Thornburg, 2011).

Methodology

A series of in-depth interviews with news editors in press departments2, managers of strategic communications companies3, and executive producers of small audiovisual production companies4 allowed the team to select the crucial processes of each of the areas studied: news publishing, strategic communications management, and production—from script approval to broadcasting—of audiovisual products.

In all three of them, the research team focused on the decision-making process, which was modeled to enrich the information content they are made of and to introduce indicators and control mechanisms to manage them more effectively. In order to do so, the team used the engineering methodology of process modeling, which reveals the essential elements of a given activity, helping to recover the vision and control of the whole process. This was conceived to solve the deficiencies of disaggregation and the scarce systematization of the production of communications, reducing its human and material costs and imbricating them in the new social and technological context.

Thus, the Work Key platform has an interdisciplinary perspective, grouping engineering, design, and communication. This perspective crosses almost all the technological project. It combines software development, project management and design skills (including interfaces, user experience, and branding) with disciplinary knowledge about different communication activities.

For each of the processes, the team identified the following levels through the sequential application of SIPOC5: 1) Components, such as objects, personal relations or abstract entities such as orders or decisions (it was also determined if these activities can be split into independent activities or if they are sub activities, which may derive in different representations of a same process). 2) Actors and recipients, including the main internal and external participants and the reasons for differentiating their access; the outsider input provider—concepts or materials—that precedes the process. 3) The adequate evaluation and Key Performance Indicators (KPI), especially those that may eventually be deployed in a dashboard.

The platform also defines access privileges for each type of internal and external user and evaluate their consistency. RACI6 matrices with the identified elements were created, as well as flowcharts using BPMN7 notation (Ko, Lee, & Lee, 2009) to synthesize the modeled process. Results of the sequential implementation of the above methodologies were contrasted and validated through a new series of interviews with opinion leaders and outstanding professionals.

Following the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK®)8 methodology, work was split into five phases: beginning, planning, execution, control, and closing. The programming and design activities were based on the Scrum9 methodology, which allowed the iterative and incremental development of the Work Key platforms, establishing successive short-term goals.

The leading team interacted as a stable team in order to provide a central focus for the development of the project and boost its common elements. Its work was based on the association, confrontation and validation of ideas and methodologies in order to achieve an innovative solution that would share a common theoretical design.

Results

The first phase concluded with the elaboration of the theory that underpinned the operative decision. For this, quality criteria related to the communication processes of the three areas were defined and operationally incorporated in the models and platforms. In addition, relationship models that include essential components—a system for recording internal sources or stakeholders and their interrelations, as well as pending issues and anticipation of events—for each communication process were developed. These aspects were included in an integrated model of actors, interrelations and essential components of communication processes. Finally, the processes were reviewed, adapted, developed and scanned through quality definitions. They were also linked to the KPIs that would influence their higher quality and the evaluation of their decisions and participants.

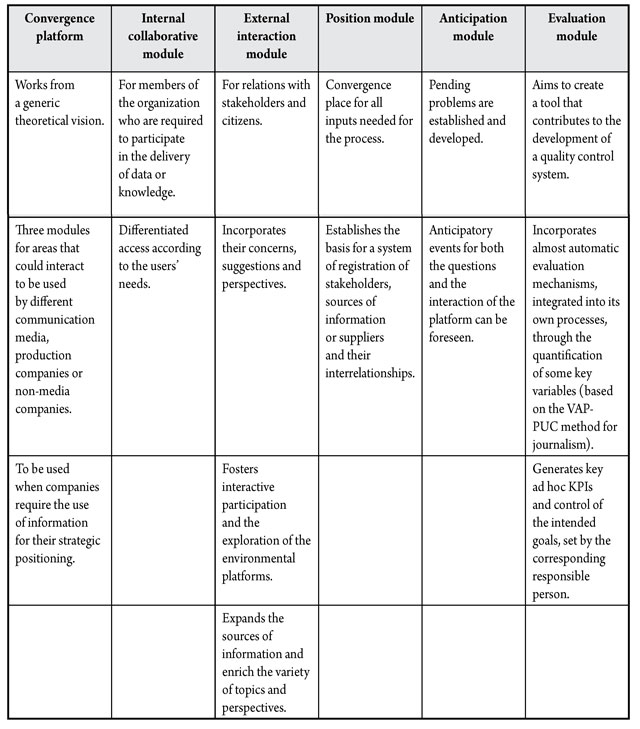

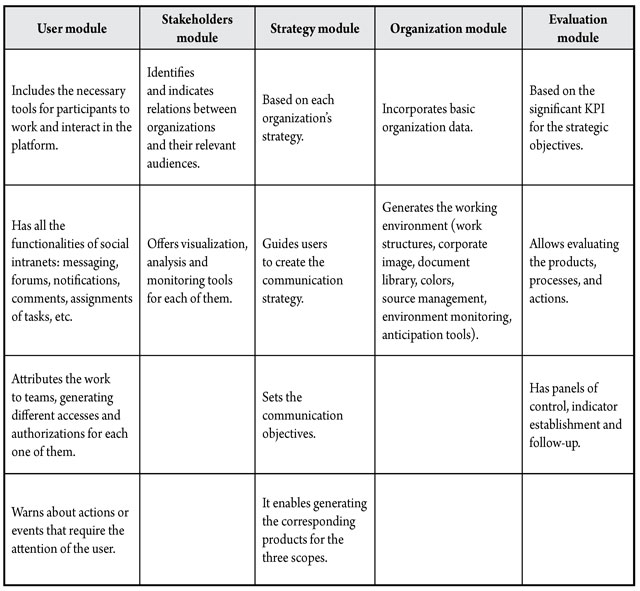

The first resulting scheme (Table 1) shows that the platform for the additional objectives proposed requires certain inputs.

Table 1. Inputs required to reach the objectives

Source: Own elaboration.

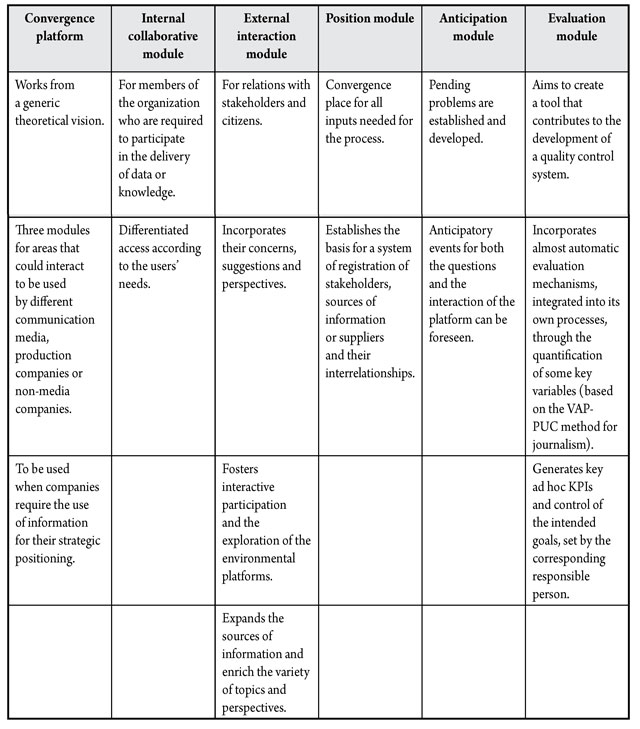

In addition, five different access levels were detected and established, as to flexibly adapt the platform to different operational situations (Table 2).

Table 2. Operational levels and their specification

Source: Own elaboration.

The general strategy sets the organization’s corporate goals. It answers the question “What is it looking for?,” while the communication strategy establishes its goals and seeks to support the fulfillment of the organization’s strategic objectives from a communications perspective. The product is defined as the element or outcome that the organization provides to different audiences, and the byproduct is defined as a unit that is part of the product developed by users. Finally, tasks are the operational and specific action within a byproduct.

In addition, the definition of different levels of interaction established as the strategic, tactical and operational domains was another underlying aspect in the development of platforms considered crucial for their usability and to achieve the goals set for the project. The first belongs to the scope of management decisions and includes planning and setting objectives for the organization with horizons of several years. Its actions—although not limited to it—are mostly strategic decision making and obtaining information from the platform, and its main contribution are strategic indicators. The tactical scope involves planning in terms of time and resources for the organization, making decisions about the processes to be executed in the medium and short terms. Its main actions are deciding to execute the processes, communicating with the team, and assigning and coordinating work , as well as obtaining and generating information. Its main contributions are tactical and strategic indicators, as well as task and team monitoring tools. As for the operational level, it mainly deals with short-term decisions and actions. The platform constitutes its workplace, executes the work/process and submits reports and results, and its main tasks are establishing a network with the boss and/or colleagues. Its main contributions are operational indicators, storage of related material, and the reflection of the conducted work.

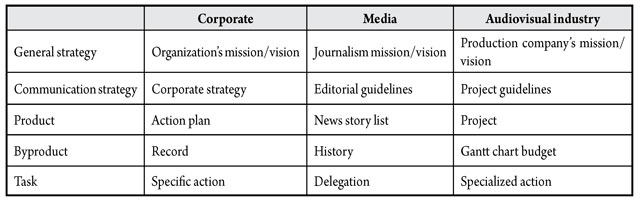

Finally, a profile of recipients was defined (Table 3).

Table 3. Profile of recipients

Source: Own elaboration.

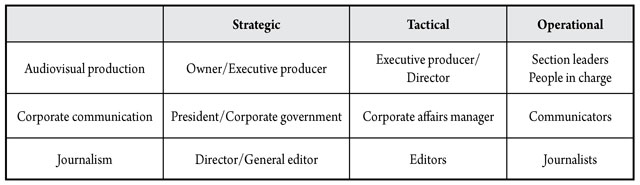

The definition prepared by Work Key established some common modules for all three platforms and some specific for each of their domains. The functionalities of the shared modules are shown in Table 4.

Table 4. Modules common to all platforms

Source: Own elaboration.

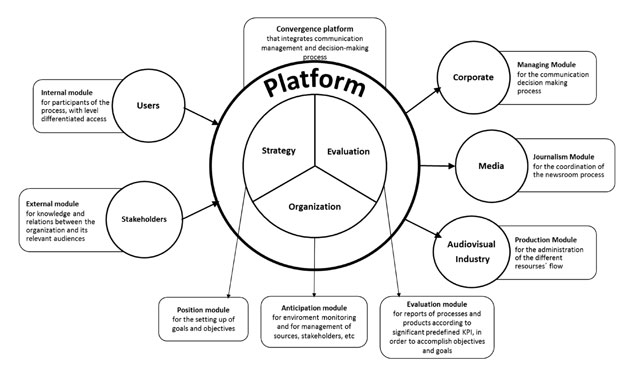

The matrices prepared for each of the platforms have common and differentiating elements, as shown in Figure 1.

Source: Own elaboration.

The specific functionalities are the ones that provide a differentiated profile from the common communication logic established in Figure 1, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Specific functionalities of Work Key

Source: Own elaboration.

Source: Own elaboration.

In addition, the objectives that optimize processes were defined and their potential impact on the areas of production, distribution and consumption were evaluated. Collaborative work through the web, quality-control mechanisms, enrichment of the elaboration process, and the introduction of other stakeholders in the productive process are the objectives that were considered as having an impact on production. On the other hand, changing consumption patterns and redistributing materials, orders and relationships by using mobile devices have an effect on production, distribution and consumption.

Finally, the Work Key platform was built through WK modules, containing the common elements (i.e., design, strategy, user, stakeholders, reports, services) and the modules specifically structured for the functionalities and features described above.

Conclusions

The Work Key platform was defined based on three types of communication processes: corporate communication (Work Key Corp), management of news story lists (Work Key News) and audiovisual production (Work Key Clap).

The most significant contributions were aimed at designing an organizational strategy that permeates all levels, knowledge and stakeholder management, and incident and crisis management. Its main objective was to improve the information and performance possibilities in terms of corporate governance. Its specific goal was to contribute to making and updating strategic decisions, anticipating crises and risks, and focusing the KPI through conceptual and practical leaps between the tactical/operational levels (KPI output and outcome) and the strategic levels of KPI.

Work Key News aimed at organizing news processes through story tracking that allowed collaborative participation and efficient modifications throughout its development. Its main focus was on the decision-making process in the media, particularly with regard to supporting the role of director/editor manager and the mobility of his/her relationship with the journalists working in each story. The team is convinced that the figure of the editor is nowadays more important than ever, since he or she is responsible for selecting and prioritizing news within the framework of unique, recognizable and valuable editorial guidelines in an environment where social sources without criteria of order are abundant.

In the case of Work Key Clap, it was discovered that, due to the mobility of its work teams, the greatest need to optimize the coordination, planning and execution of audiovisual production was in independent audiovisual production companies. The proposed platform allows better management of time and resources and aims to develop an efficient organization of people working at each stage of the projects. Its fundamental concept focused essentially on the executive producer, considered as the origin and the end of each production, in a structure of circular layers that characterizes this activity. The research team decided not to include the stages of authorship (mainly those related to the development of the idea and the script) to respect the creativity and uniqueness of that part of the project.

Work Key Corp must continue to advance in the development of universally recognized performance indicators for corporate communication, allowing better management of its role and legitimacy within organizations, as well as its relations and consideration of stakeholders.

Work Key News faces the challenge of constant change in the news activity. The platform seems to have significantly improved the work relation between geographically distant participants and the internal relationships within the news generation process, as well as source management and the rapid incorporation of key performance indicators based on the Journalistic Added Value method (Pellegrini et al., 2011) (tested in several countries over two decades) in an original and collaborative way.

Work Key Clap creatively incorporated a new perspective for the productive process in the audiovisual field, but there could be a barrier to adapt to such an innovative change in a professional environment used to work with computers but not with specific tools.

In general terms, it is worth noting the potential impact of modeling all communication processes involved with a common perspective and a theoretical framework. This is a theoretical support that did not previously exist and that generates a flow of new knowledge to support future projects, as well as the definition of transversal skills to prepare professionals for multitask work.

The main challenges of intangible management covered by this project are processes affected by soft variables and by uncertainty about the environment that continuously affects the management of communication. Therefore, it is very important to avoid reductions in such complex processes that are full of nuances and subtleties. This platform represents a helpful solution that handles the mechanical and routine aspects of the three industries, but in no way seeking to replace aspects of authorship or creativity. The team also sought to support those processes that involve a large number of actors that need to be coordinated, whereas it can only serve marginally to support actions where a single actor is involved, since in that case the margin of creativity is greater.

The existence of new technologies allows and requires great changes in the different aspects of the generation and diffusion of the contents of communication and information and in the management of its intangible byproducts. It allows the construction of networks and virtual environments that emulate the processes of information collection and dissemination, hitherto conducted through various personal methods. It is also possible to add elements of interactivity, incorporate new stakeholders, and real-time exchange of background and perspectives.

Real-time collaborative work in a network is not a common initiative in the field of communications, much less attempting to have a common structure of interrelations for various types of products. Although the strategic objectives of each of the Work Key products are the same, the context of use and the ways in which users are faced with an online web-based technological tool, their cognitive approach to the platform and their objectives are different. Therefore, it is important to point out that the solution is based on constantly tested hypotheses reformulated by communicators, designers and engineers and that their variations were iteratively validated, by real users, throughout all their development phases.

The interdisciplinary work was a constant challenge that required a correct interaction between the disciplines to generate an internal information flow as to achieve the project objectives and produce results. The platform and equipment structure of each phase had to be adapted to meet the needs derived from a greater understanding of the processes and greater precision of the end user.

A future and no less important general challenge is to integrate these kinds of systems into normal work routines. The starting point to achieve that goal is to recognize the need to systematize the communication professional processes, but it is also necessary that the tool is considered friendly, useful and daily applicable by people working in the covered fields.

From the very beginning, the design of the graphical interface of this platform considered the incorporation, in a friendly way, of not only one particular user, but of multiple users working simultaneously, interacting, accessing contents and diverse sources of information, and generating new products that have an impact on other decision-making processes.

It is important to note that Work Key has proved to be a valuable learning tool. The underlying methodology allows professionals and university students to perform tasks under certain systematizations that facilitate and incorporate certain work habits that undoubtedly contribute to the quality of the resulting product.

Notas

1 This innovation was developed during Project CONICYT- FONDEF # D08i1082 “Information integration system: derived products,” carried out in close collaboration with VTR, Codelco, Enersis, Endesa, Chilectra, and the Inter-American Development Bank.

2 Specifically, for the journalism aspect of the project, fourteen in-depth interviews were done to press directors, radio, TV and website editors. As a first validation process, we made twenty individual presentations to two media directors, ten editors, two press room-producers and six journalists, all of them followed by critical discussions. As a final step of validation, we applied several usability tests with undergraduate and graduate students from the School of Journalism of Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile (UC) during a whole year.

3 For the corporate communication aspect of the project, ten in-depth interviews were done to Vice Presidents of Communications. As a first validation process, we made a survey send to fifty large companies (public, private, national, and transnational), and institutions (public, trade associations, and NGOs.), that were leaders in their respective sectors and had a formal Communications Department with a Vice President in charge. Thirty-three valid answers were received. As a final step of validation, we applied several usability tests with the companies associated to the project: Codelco, Endesa, Chilectra, and Enersis.

4 For the audiovisual production aspect of the project, 11 in-depth interviews were done to independent producers and film directors in the Chilean audiovisual industry. As a first validation process, we made a survey of ninety-nine other independent producers and film directors. As a final step of validation, we applied several usability tests to two audiovisual projects during four months of execution (pre-production, production, and filming).

5 SIPOC analysis is a tool used to define all the elements

relevant to a processes improvement project before it starts. It helps to

differentiate a complex process and is typically used during the measurement of

Six Sigma’s DMAIC methodology (Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, Control), a

set of techniques and tools for process improvement developed by Motorola and

in use since the late 1980s. To summarize, this method looks to explain five

basic aspects:

- What does

the process do? (P: process)

- What

inputs does the process need to be carried out? (I: input)

- Who

provides these inputs? (S: supplier)

- What is

the result of the process? (O: output)

- Who is

the recipient of these results? (C: customer)

6 The Responsible, Accountable, Consulted, Informed (RACI)

matrix assumes that any activity has one and only one person responsible for

it, and that it must be executed by one or several people, or by some system.

It is also possible that it will be necessary to consult or inform other

people, different from the person responsible and the ones executing it. For

each activity, the members of the organization are explicitly identified

according to their positions with their corresponding role:

- The

person in charge of overseeing the correct completion of the activity (R:

responsible)

- One of

several people who participate in executing the activity (A: accountable)

- One of

several people who are consulted as part of the execution of the activity (C:

consulted)

- One of

several people who are informed on the result of the activity (I: informed)

7 Business Process Modeling Notation (BPMN): Initially developed by the Business Process Management Initiative as a standard for representing processes, it is specifically designed for representing the sequence of activities and messages that flows between different participants.

8 See the Project Management Institute (PMI), an organization founded in 1969 to achieve significant improvements in project management. One of its most visible products is the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK), an internationally recognized standard for managing projects (IEEE, ANSI). Its first edition was published in 1987.

9 Scrum is a work model that defines a set of practices and roles for the development of technological applications. The development is split into work cycles with periods no greater than seven days, where programming efforts are focused on limited objectives, under permanent evaluation, until a functional version of the platforms is achieved.

References

Argenti, P. A. (2009). Corporate communication (5th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw Hill.

Becker, L. B., & Tudor, V. (2009). News organizations and routines. In K. Wahl-Jorgensen & T. Hanitzsch (Eds.), The handbook of journalism studies (pp. 59–72). New York, NY: Routledge.

Bernal-Triviño, A. I. (2015). Tecnología, redes sociales, política y periodismo. ¿Pluralidad informativa o efecto bumerán? Cuadernos.info, 36, 191–205. doi: 10.7764/cdi.36.647

Boczkowski, P. J. (2004). The processes of adopting multimedia and interactivity in three online newsrooms. Journal of Communication, 54(2), 197–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2004.tb02624.x

Bradshaw, P., & Rohumaa, L. (2013). The online journalism handbook: Skills to survive and thrive in the digital age. New York, NY: Routledge.

Briggs, M. (2012). Journalism next: A practical guide to digital reporting and publishing (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Sage.

Cabezón, L. A., & Gómez-Urdá, F. (2003). La producción cinematográfica. Madrid, Spain: Cátedra.

Calderón, C. (2011). La imagen es la identidad. Santiago, Chile: eBooks Patagonia.

Carlson, M. (2007). Order versus access: News search engines and the challenge to traditional journalistic roles. Media, Culture & Society, 29(6), 1014–1030. doi: 10.1177/0163443707084346

Celery, A. (2001). Manual de producción: cine, televisión, publicidad. Santiago, Chile: LOM.

Chung, D. S., Eunseong, K., Trammell, K. D., & Porter, L. V. (2007). Uses and perceptions of blogs: A report on professional journalists and journalism educators. Journalism & Mass Communication Educator, 62(3), 305–322. doi: 10.1177/107769580706200306

Diakopoulos, N., De Choudhury, M., & Naaman, M. (2012). Finding and assessing social media information sources in the context of journalism. Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems, 2451–2460. Retrieved from http://www.nickdiakopoulos.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/07/SRSR-diakopoulos.pdf

Du, Y., & Thornburg, R. (2011). The gap between online journalism education and practice: The twin surveys. Journalism & Mass Communication Educator, 66(3), 217-230. doi: 10.1177/107769581106600303

Fleisher, C., & Bensoussan, B. (2007). Business and competitive analysis. Effective application of new and classical methods. Upper Saddle River, NJ: FT Press.

Freeman, R. E., & Reed, D. L. (1983). Stock holders and stakeholders: A new perspective on corporate governance. California Management Review, 25(3), 88–106. doi: 10.2307/41165018

Gillmor, D. (2006). We the media: Grassroots journalism by the people, for the people. Sebastopol, CA: O’Reilly Media, Inc.

Grunig, J., & Hunt, T. (2000). Dirección de relaciones públicas. Barcelona, Spain: Gestión.

Harcup, T. (2015). Journalism: Principles and practice. New York, NY: Sage.

Harcup, T., & O’Neill, D. (2001). What is news? Galtung and Ruge revisited. Journalism Studies, 2(2), 261–280. doi: 10.1080/14616700118449

Jacoste-Quesada, J. G. (2004). El productor cinematográfico. Madrid , Spain: Síntesis.

Ko, R. K. L., Lee, S. S. G., & Wah Lee, E. (2009). Business process management (BPM) standards: A survey. Business Process Management journal, 15(5), 744–791. doi: 10.1108/14637150910987937

Lamelas-López, M., Pont-Sorribes, C., & Alsius, S. (2016). Radiografía de las exclusivas en el periodismo político español: seguimiento y factores de competencia. Cuadernos.info, (38), 121–136. doi: 10.7764/cdi.38.673

Pavlik, J. (2000). The impact of technology on journalism. Journalism Studies, 1(2), 229–237. doi: 10.1080/14616700050028226

Pellegrini, S. (2015). Ordenando el caos. Gestión y modelamiento de procesos en la industria de la comunicación. Santiago, Chile: Ediciones Universidad Católica de Chile.

Pellegrini, S., Puente, S., Godoy, S., Fernández, F., Julio, P., Martínez, J. E., Soto, J. A., & Grassau, D. (2009). Ventanas y espejos: televisión local en red. Santiago, Chile: El Mercurio Aguilar.

Pellegrini, S., Puente, S., Porath, W., Mujica, C., & Grassau, D. (2011). Valor agregado periodístico: la apuesta por la calidad de las noticias. Santiago, Chile: Ediciones Universidad Católica de Chile.

Poell, T., & Borra, E. (2012). Twitter, YouTube, and Flickr as platforms of alternative journalism: The social media account of the 2010 Toronto G20 protests. Journalism, 13(6), 695–713. doi: 10.1177/1464884911431533

Porter, M. E., & Kramer, M. R. (2011). Creating shared value. How to reinvent capitalism and unleash a wave of innovation and growth. Harvard Business Review, 89(1), 2–17. Retrieved from http://www.philosophie-management.com/docs/2013_2014_Valeur_actionnariale_a_partagee/Porter__Kramer_-_The_Big_Idea_Creating_Shared_Value_HBR.pdf

Puente, S., Edwards, C., & Delpiano, M. O. (2014). Modelamiento de los aspectos intervinientes en el proceso de pauta periodística. Palabra Clave, 17(1), 186–208. Retrieved from http://www.scielo.org.co/pdf/pacla/v17n1/v17n1a08.pdf

Rudat, A., Buder, J., & Hesse, F. W. (2014). Audience design in Twitter: Retweeting behavior between informational value and followers’ interests. Computers in Human Behavior, 35, 132–139. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2014.03.006

Sainz, M. (2014). El productor audiovisual. Madrid, Spain: Síntesis.

Soto, J. A. (2013). Estandarización de organigramas y modelamiento del proceso de producción audiovisual: una propuesta basada en la toma de decisiones. Cuadernos.info, 33, 121–131. doi: 10.7764/cdi.33.525

Soto, J. A. (2015). Manual de producción audiovisual. Santiago, Chile: Ediciones UC.

Stanton, W. J., Etzel, M., & Walker, B. (2007). Fundamentos de marketing. New York, NY: Mc Graw-Hill.

Thurman, N. (2008). Forums for citizen journalists? Adoption of user generated content initiatives by online news media. New Media & Society, 10(1), 139–157. doi: 10.1177/1461444807085325

Tironi, E., & Cavallo, A. (2003). Comunicación estratégica. Vivir en un mundo de señales. Santiago, Chile: Taurus.

Van Riel, C., & Fombrun, C. J. (2007). Essentials of corporate communication. New York, NY: Routledge.

Villafañe, J. (2013). La buena empresa. Propuesta para una teoría de la reputación corporativa. Madrid, Spain: Pearson.

Westerman, D., Spence, P. R., & Van Der Heide, B. (2014). Social media as information source: Recency of updates and credibility of information. Journal of Computer‐Mediated Communication, 19(2), 171–183. doi: 10.1111/jcc4.12041

Worthington, C. (2009). Producción. Barcelona, Spain: Parramón.