|

Artículos Framing of Electoral Processes:

|

Carlos Muñiz1

Alma Rosa Saldierna2

Felipe de Jesús Marañón3

1 orcid.org/0000-0002-9021-8198. Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, México. carlos.munizm@uanl.mx

2 orcid.org/0000-0003-1805-9740. Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, México. alma.saldiernas@uanl.mx

3 orcid.org/0000-0002-0705-6336. Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, México. felipe.maranonl@uanl.mx

Recibido: 2017-06-07

Enviado a pares: 2017-06-12

Aprobado por pares: 2017-07-18

Aceptado: 2017-10-24

Para citar este artículo / to reference this article / para citar este artigo: Muñiz, C., Saldierna, A. R. y Marañón, F. J. (2018). Framing of electoral processes: The stages of the campaign as a moderator of the presence of political frames in the news. Palabra Clave, 21(3), 740-771. DOI: 10.5294/pacla.2018.21.3.5

Abstract

Mass media plays a crucial role during the election campaigns, because, by promoting a particular framing to present issues and candidates involved in the campaigns citizens are granted access to the political debate. To analyze the political framing carried out by the media during the 2015 gubernatorial election campaign of Nuevo León, Mexico, a content analysis of the news stories published by television and the press was developed. Findings made it possible to detect a different use of news frames by both media. While the frame of strategic game dominated in television, the press emphasized a treatment of conflict. In addition, a moderation effect of the campaign stages was observed in the use of different news frames, increasing the use of strategic game and debate and political agreement frames by television, while the press maintained a constant presence of news frames.

Keywords: Framing; news frames; elections campaign; press; television (Source: Unesco Thesaurus).

Resumen

Los medios de comunicación juegan un papel crucial durante las campañas electorales, pues, a través de la promoción de un tratamiento informativo particular para presentar los temas y candidatos que participan en las mismas, permiten a la ciudadanía tener acceso al debate político. Para analizar el framing político realizado por los medios durante la campaña electoral, se realizó un análisis de contenido de las noticias publicadas por la televisión y la prensa durante las elecciones a la gubernatura de Nuevo León, México, de 2015. Los hallazgos permitieron detectar un uso diferente de los encuadres noticiosos por ambos medios, pues mientras que en la televisión dominaba el enfoque de juego estratégico, la prensa enfatizó más un tratamiento de conflicto. Además, se observa un efecto moderador de las etapas de campaña en el uso de los diferentes encuadres, lo que hizo que se incrementara el juego estratégico y debate y acuerdo político en la televisión, mientras que la prensa mantenía una presencia constante de los encuadres.

Palabras clave: Framing; encuadres noticiosos; campaña; elecciones; prensa; televisión (Fuente: Tesauro de la Unesco).

Resumo

Os meios de comunicação de massa têm um papel crucial durante as campanhas eleitorais porque, ao promoverem um enquadramento particular para apresentar questões e candidatos envolvidos nas campanhas, garantem aos cidadãos o acesso ao debate político. Para analisar o enquadramento político realizado pela mídia durante a campanha eleitoral ao governo do estado de Nuevo León, no México, em 2015, foi feita uma análise de conteúdo das notícias publicadas pela televisão e pela imprensa. As descobertas permitiram detectar um uso diferente do enquadramento noticioso em ambas as mídias: enquanto o cenário do jogo estratégico dominava na televisão, a imprensa enfatizava um tratamento de conflito. Além disso, observou-se um efeito moderador das etapas da campanha no uso de diferentes enquadramentos: na televisão houve um aumento do uso do jogo e do debate estratégico e também do acordo político, enquanto a imprensa manteve a presença constante dos enquadramentos noticiosos.

Palavras-chave: Campanha eleitoral; enquadramento; enquadramento noticioso; imprensa; televisão (Fonte: Tesauro da Unesco).

Introduction

The media plays a crucial role in election campaigns, by creating a necessary link between political parties, candidates, and citizens, thanks to their coverage, so much that it has been suggested that this coverage is a currency or a tool with which democracies operate to consolidate (Gerth & Siegert, 2012). Through the coverage provided in their news stories, the media transmits the programmatic proposals, as well as the different positions of the contenders on important issues—crucial information for citizens who will eventually make their decisions based on that coverage (Matthes, 2012). Thus, the informative treatment or framing that media will confer to the issues of the campaign will be decisive (Schuck, Vliegenthart, Boomgaarden, Elenbaas, Azrout, van Spanje, & de Vreese, 2013). In other words, framing refers to the way in which the proposals, discussions, and strategies of the campaign are presented in the news, emphasizing or excluding possible approaches about the existing reality (Muñiz, 2015).

Studies on election campaign coverage have found that the media tends to emphasize the use of two news frames traditionally linked to politics (Aalberg, Strömbäck, & de Vreese, 2012; Muñiz, 2015). Usually, the campaign focuses on a strategic game frame, which tends to present politics and the electoral process itself as a strategy game and different political tactics developed by candidates, political parties or rulers to improve their chances of triumph (Dimitrova & Kostadinova, 2013). However, in the face of this coverage, news stories can also present a thematic or issue-centered approach with the use of issue frame, which tends to emphasize the debate about problems and information proposals related to the actors that make them (Rhee, 1997).

While many of the studies on framing election campaigns have focused on these two generic news frames, it is common for media to use other frames in their election coverage, such as the conflict frame approach, which has been seen by some authors as consubstantial to politics (de Vreese, 2014; Schuck, Vliegenthart, & de Vreese, 2016). Conflict framework is a generalist news frame; in other words, it can be used in any news story to emphasize the disagreement between the different actors involved in politics (Neuman, Just, & Crigler, 1992; Semetko & Valkenburg, 2000; Strömbäck & Luengo 2008). Keeping this in mind, it leads us to linking conflict with negativity, while other authors have postulated that the conflict frame should be conceived more as an option for political debate, a place where opinions are confronted by fighting for consensus, commitment, or cooperation (Lengauer, Esser, & Berganza, 2012; Sevenans & Vliegenthart, 2016).

According to this reality, which is present in the existing literature, this study aims to analyze the framing carried out by the media during the election campaign, using as reference the four abovementioned frames—that is, if the campaign is framed in terms of: 1) strategic game; 2) issue; 3) conflict; or 4) debate or political agreement. The paper also aims to determine whether the main traditional media intervening in the agenda setting during the campaign, such as television and the press, have similar or different patterns of news frame use throughout the stages of the electoral process. For this purpose, the study worked with data gathered from the gubernatorial election campaign in Nuevo León, Mexico, which took place between March and June of 2015.

This election was highlighted by two main factors: the important role played by the media, particularly by social networks, for the candidates (Berumen & Medellín, 2016); and, for the first time in a Mexican election, real options of success for independent candidacies (Nuncio, 2015). In both cases, Jaime Rodríguez Calderón "El Bronco", who was the eventual winner of the election, played a crucial role. In addition to being the first independent candidate to be elected Governor, he marked the process's future by establishing a campaign strategy focused mainly on the use of social media and social networks (Nuncio, 2015), through the use of an "emotion marketing" and very high interaction levels across social networks (Berumen & Medellín, 2016). On the other hand, traditional media played an important role, although a greater coverage was focused on strengthening the image of traditional party candidates.

The Informative Framing of Politics

The journalistic work involves the elaboration of information, starting from the selection of subjects that are given greater importance than others (Sevenans & Vliegenthart, 2016). However, this professional exercise does not end there; aside from pointing out important aspects, the media also develops a process of translation of information, using certain frames or approaches and offering a particular informational treatment of reality (D'Angelo, 2002; de Vreese, 2003; Entman, 1993; Matthes, 2012). Framing theory analyzes precisely these news frames employed by journalists to produce information. Although the starting points of view for their study are different, for the purposes of this paper, it will be interesting to define them by focusing on the way they are presented in the news—that is, analyzing the role of the issues in the construction of news through the use of certain news frames, by selecting and highlighting certain key aspects within the information content (Matthes, 2009; Valkengburg, Semetko, & de Vreese, 1999).

This process entails, in Entman's (1993) words, the selection of "some aspects of a perceived reality and make them more salient in a communicating text, in such a way as to promote a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and/or treatment recommendation for the item described" (p. 52). It is observed that framing involves selecting certain frames within the news texts, which help to structure the information and give it meaning, highlighting the positions maintained in relation to a subject (de Vreese, 2012; Matthes, 2012). In the journalistic field, they have been defined as "a particular way in which journalists compose a news story" (Valkengburg et al., 1999, p. 550). For its part, Muñiz (2015) points out that the news frame is a "structure present in the information content," used "to elaborate its information and to provide a certain angle, focus, perspective or treatment to the subject, in order to make it more compressible for the public" (p. 74).

The framing theory has been positioned as one of the predominant theoretical approaches in the literature in communication (Rinke, Wessler, Löb, & Weinmann, 2013), something that has also been observed in studies in the area of political communication (Boomgaarden, 2017; Matthes, 2009; Schuck, 2017). Consequently, several studies have been carried out with the aim of detecting the news frames employed in the media when they exhibit political information, both in public policy debate and electoral processes (Schmuck, Heiss, Matthes, Engesser, & Esser, 2017; Schuck et al., 2013; Schuck, Boomgaarden, & de Vreese, 2013). At that moment the work of politicians, candidates, and parties to establish their points of view on reality is intensified, setting a relationship between media and politicians where the news frames of both actors compete to position themselves inside the informational text (Gerth & Siegert, 2012; Hänggli & Kriesi, 2012).

As noted above, framing refers to the process of creating, selecting, and establishing news frames by journalists (Matthes, 2012), through which political issues are interpreted (Gerth & Siegert, 2012). Consequently, the elements that make up the news frames about politics reside in the rhetoric of the political class, and they must be understood as "bundles of consistent issue-arguments, originally proposed by opponents or proponents" in a campaign or political debate (Matthes, 2012, p. 254). Media and journalists, on the other hand, will select and use a specific journalistic frame or frames to present that political event to society (Strömbäck & Dimitrova, 2011). Among the studies that have sought to determine the political frames is the one carried out by Cappella and Jamieson (1997), who, following previous proposals, suggest the existence of two generic news frames in the political coverage: the issue frame and the strategic frame.

The strategic frame is used to emphasize strategies and tactics followed by candidates and/or parties positioning themselves in a situation of advantage or achieving certain goal like, for example, getting leadership, winning the elections or presenting reasons why they develop certain political actions (Aalberg, Strömbäck, & de Vreese, 2012; Cappella & Jamieson, 1997; Schmuck, Heiss, Matthes, Engesser, & Esser, 2017). Very close to this conceptualization is the game frame, usually used in the literature to explain the media coverage of the election campaign. The game frame tends to present politics as a competition or a game between parties and/or candidates aiming to impact public opinion and to gain advantage in the electoral race, which results in the exhibition of politics as a battle of winners and losers (Boomgaarden, 2017; Cappella & Jamieson, 1997; Schmuck et al., 2017).

Both frames have been seen as two very close manifestations in the treatment of politics, so that many authors consider them similar and interchangeable (Berganza, 2008; Rinke, Wessler, Löb, & Weinmann, 2013). On the other hand, other authors argue its unification, understanding that, at a meta-conceptual level, it is logical to combine it into a single large strategic game frame (including the two dimensions of the original frames) (Aalberg et al., 2012; de Vreese, 2005; de Vreese & Semetko, 2002). Beyond the conceptual debate on its recommended or non-recommended combination, in this paper we will consider it as a single frame, following the definition provided by Dimitrova and Kostadinova (2013). For these authors, the frame of strategic game presents policy "coverage focusing on political strategy and tactics, current standing in the polls, who is winning and who is falling behind, and other horse-race aspects of the campaign" (p. 81).

In addition to the informative treatment of politics from the strategic game, the existence of a coverage tending to focus more on the political issue and its edges has also been considered (Muñiz, 2015; Shehata, 2014). Thus, the issue frame tends to be used when coverage is sought to emphasize "proposals for the problems, information about who is advocating which policy alternative, and consequences of the problems and proposals" (Rhee, 1997, p. 30). As a result, it is seen as an approach that prioritizes the coverage of substantive policy issues, such as programmatic proposals made by the candidates (Aalberg et al., 2012), as well as the debate about them and their implications for the citizenship, beyond the impact on the positioning of the politician himself (Dimitrova & Kostadinova, 2013; Muñiz, 2015; Pedersen, 2012).

Regardless of the countries and whether or not the information was an election campaign, numerous investigations that have studied the presence of both news frames have detected the prevalence of the strategic game frame versus the issue frame in media coverage (Aalberg et al., 2012; Dimitrova & Kostadinova, 2013). For example, Rinke et al. (2013) detected a greater strategic game coverage than issue one in television during the 2009 German elections. Berganza (2008) detected this same predominant presence in the coverage made by the Spanish press during the elections to the European Parliament of 1999 and 2004 and the referendum on the Constitutional Treaty of 2005. Moreover, Schuck et al. (2013) detected the prevalence of the strategic frame in the coverage of 27 countries of the 2009 European parliamentary elections. In the Mexican case, Muñiz (2015) has detected how the use of the strategic game frame in the digital press dominated during the 2012 presidential elections. Finally, within the cross-cultural studies, Strömbäck and Dimitrova (2011) observed the preponderance of this frame in the media coverage of elections of the United States (2008) and Sweden (2006).

Moreover, the comparative study regarding the use of frames in both press and television has also been approached. This is the case of the study by Elenbaas and Vreese (2008), who detected that the strategic game frame was more observed in television news than in press news, across the 2005 European Referendum coverage in the German media outlets. A similar result was found by de Vreese and Semetko (2002) concerning the coverage of the 2000 Danish Referendum related to the euro introduction. For his part, Shehata (2014) found that the strategic game frame dominated the television coverage of the 2010 election campaign in Sweden, while issue framing dominated in press coverage. Finally, Schmuck et al. (2017) have concluded that television exhibited a greater degree of strategic play frame in its coverage of politics than the one observed in the press. Considering all this evidence, this paper will work with the following hypotheses about the use of these two news frames:

H1: The strategic game frame has a greater presence in the television coverage of the election campaign than in the press coverage.

H2: The issue frame has a greater presence in the press coverage of the election campaign than in television coverage.

The Conflict Versus the Debate and Agreement within the Political Framing

It is common for information content to use the conflict frame to deal with public issues (de Vreese, 2012; Schuck et al., 2013), both in coverage of policy issues and, above all, of election campaigns (Dimitrova & Strömbäck, 2012; Schuck, 2017). Consequently, it has been argued that this approach or framing of conflict is consubstantial to politics and it became a prominent ingredient for the political news coverage (de Vreese, 2014; Schuck et al., 2013). Although the conflict frame is quite exposed by the media, especially in the information offered on politics and election campaigns, it is also adopted by other kind of news of events closer to the everyday life of people (de Vreese, Peter, & Semetko, 2001; Price & Tewksbury, 1997). In fact, Semetko and Valkenburg (2000) already pointed out in their study how conflict constitutes a generalist frame, so that it can be used in any news to emphasize "conflict between individuals, groups, or institutions as a means of capturing audience interest" (p. 95).

The explanation for this strong use of the conflict news frame in the media can be found for several reasons. There is no doubt that negativity, an aspect strongly linked to the conflict (Berganza, 2008; Lengauer et al., 2012), is one of the news values of informational messages, making them more relevant to the media (Sevenans & Vliegenthart, 2016). In addition, as the conflict is shaped in the news story by the opposition of positions on a subject, its use can contribute to obtain a more objective and balanced information (Bartholomé, Lecheler, & de Vreese, in press; de Vreese, 2004; Schuck, Vliegenthart, & Vreese, 2016). In addition, it can also be used by the media to capture the public's interest (Schuck et al., 2016), as well as to increase the exposure and reading time of the information (Zillmann, Chen, Knobloch, & Callison, 2004). Therefore, this confrontation between actors can increase the probability of information impact on the audience, resulting in a cognitive channeling that helps to shape their opinions and attitudes (de Vreese, 2014; Schuck et al., 2016).

The media use of conflict frame has been widely studied, both in content linked to politics and in general issues, such that this frame is one of the most used generic news frames (de Vreese, 2005; Lengauer et al. 2012). Many of these studies have been carried out in Europe, undoubtedly by the influence of the work of Semetko and Valkenburg (2000), who laid the theoretical and operational bases for the analysis of the conflict. The authors analyzed the presence of the conflict in the press and television news during a meeting of heads of state and government of the European Union in 1997, based on previous works such as that of Neuman, Just and Crigler (1992). Their data revealed that the conflict was the second most used frame, its presence dominating among newspapers. Subsequent studies have detected high levels of presence in the policy information (de Vreese et al., 2001), highlighting the negativity of the press in comparison to television (Berganza, Arcila, & de Miguel Pascual, 2016). Regarding electoral coverage, previous works have found similar patterns where the conflict treatment predominates (Strömbäck & Luengo, 2008), which is particularly noticeable in press reports (Schuck et al., 2013).

In the Latin American region, fewer studies have evaluated the news framing. Among these investigations, there is one from Aruguete (2010), who, when analyzing the press coverage of the last stage of the ENTEL privatization process, detected a strong presence of the conflict. There is also the work of Muñiz and Ramírez (2015), who analyzed the press coverage of drug trafficking in Mexico and detected a strong presence of the conflict frame. More recently, Gronemeyer and Porath (2017) have detected, in a longitudinal study for 3 years, that the conflict frame was the most used to provide coverage on politics in Chilean press. Regarding election campaigns in Mexico, Lozano, Cantú, Martínez, and Smith (2012) point out that, since the 1990s, the media devoted a good part "of their electoral coverage to attacks, disqualifications, personalities and the position of the two main contenders in opinion polls instead of focusing on the issues and proposals" (p. 177). For his part, Muñiz (2015) has detected, in his analysis of digital press during the 2012 Mexican presidential campaign, a coverage with the prevalence of a language of war and the idea of the existence of winners and losers.

However, it is assumed that conflict should not necessarily imply negative coverage, but it should be understood as the confrontation of different ideas and positions around a subject, which is beneficial for democracy (Berganza, 2008; Lengauer et al., 2012; Schuck et al., 2016). This is because it can provide citizens with elements to make decisions and even to encourage their participation in political processes (Boomgaarden, 2017; Sevenans & Vliegenthart, 2016). Therefore, some authors propose that conflict is, beyond negativity, a necessary and preceding step to decision making and consensus to solve political problems (Schuck, 2017; Schuck et al., 2016). Nevertheless, there is no doubt that the traditional way to measure the conflict frame in the news stories emphasizes more the disagreement between actors than the agreement they can or should achieve.

Previous studies traditionally have been operationalized the news frame understanding that it refers to the existence of different positions, disagreement between actors, reproaches or condemns made by some actors against others and even making an treatment about the existence of winners and losers or the conflicting nature of the relationship between those actors (Boomgaarden, 2017; Neuman et al., 1992; Semetko & Valkenburg, 2000). Faced with this reality in the framing literature, other authors such as Bartholomé et al. (in press) argue that conflict must overcome a vision that generally tied it to a negative tone in the news. Likewise, these authors differ about the fact that it must necessarily entail the guilt of an actor for an issue or that it should refer to a "horse race journalism". Along the same line, we have observed the proposal of Sevenans and Vliegenthart (2016), for whom this news frame should be seen as a political debate and a confrontation of opinions. On the other hand, Lengauer et al. (2012) propose to measure the frame as a bipolar scale, where conflict is opposed to consensus, commitment, and cooperation.

From these ideas mentioned above, in this paper a new scale was worked out to measure the news frame that was denominated "debate and political agreement." The scale consists of four items that point out whether the news story emphasizes the debate between political actors about a specific subject or issue, if it emphasizes agreement reached by the actors after a negotiation related to an informed decision, if it presents the political decision making as an agreement between actors, or if it presents political decision-making as listening to each other, mutual understanding, etc. Taking all of this into account, the study aimed to contrast the following hypothesis and to answer the following research question about the use of these two news frames:

H3: The conflict frame has a greater presence in the press coverage of the election campaign than in the television coverage.

RQ1: Are there differences between television and press regarding the use of the debate and political agreement frame?

The Effect of the Stages or Phases of the Election Campaign on Framing

The study of the informative treatment of election campaigns has tended to be carried out from cross-sectional approaches, which entail the comparison of the framing done by different media, or from cross-cultural studies between different countries, as described in the previous sections. However, there is a clear lack of studies carried out to evaluate the trend in the use of news frames between different electoral processes from a longitudinal content analysis perspective (Dimitrova & Strömbäck, 2012). In this regard, we can mention examples such as the study carried out by Berganza (2008) in Spain or the study by Dimitrova and Kostadinova (2013) in the case of Bulgaria. Both studies converge on similar conclusions about the use of politics news frames: when the information on election campaigns is presented in these countries, we can see how the strategic game frame approach dominates versus the issue frame, a difference that also tended to increase from one election to next one. These studies show a promising and still incipient line of work, related to the development of longitudinal studies on political framing.

Furthermore, investigations that use different political news frames in the course of the electoral process are limited, especially because election campaigns are not static—they tend to vary in coverage and intensity of informational treatment offered to proposals, candidates, etc. Usually, the election has been divided into three stages or phases that define the course of the election campaign (Freidenberg & González Tule, 2009; Nohlen, 1998). Positive approaches usually dominate in the first stage or initial phase, where the presentation of the candidates dominates. The second or intermediate stage is usually dominated by strategies of programmatic presentation and government proposals presented by the candidates. But, as Freidenberg and González Tule (2009) point out regarding the 2012 Mexican election campaign, a negative campaign with attacks between candidates is also present at this stage. Finally, the third stage or final phase is the most crucial for candidates; in this phase, horse race presentation and strategic game frame tend to be emphasized through polarization between candidates and their strategies to obtain the victory and win the election.

Among the studies related to framing, few of them exhibit longitudinal comparisons in the campaign. In their work, Schuck et al. (2013) found that, as the election campaign for the 2009 European Parliament progressed, the use of horse race frame by media tended to increase in the 27 countries analyzed. However, the other news frames examined did not exhibit the same behavior. For his part, Muñiz (2015) analyzed the Mexican presidential campaign of2012 from the generation of three phases, dividing the variable related to the moment of publication of the news, taking as reference the two electoral debates that took place in the aforementioned election. The author detects that, while issue frame tended to decrease, the strategic game frame tended to increase, so that in the first stage of the election campaign the differences were smaller, while in the final stretch of the campaign the differences became greater with respect to the use of both news frames. Considering the antecedents presented, this research aimed to answer the following research question regarding the use of the policy news frames:

RQ2: Does the election campaign through its stages have a moderation effect on the use of the different news frames by the press and television?

Method

Sample and unit of analysis

In response to the research questions and hypotheses raised, a content analysis of the news stories published in press and broadcasted in television during the election campaign for the governor of Nuevo León, Mexico, in 2015, was conducted. In the case of the press, the news stories published by regional newspapers ABC (3.8% of the total), El Porvenir (5.3%), El Horizonte (15.0%) and El Norte (9.9%) and the regional versions of Reporte Indigo (5.3%) and Publimetro (7%) were analyzed. As for television, the news broadcasted on the nightly news programs of Televisa (7.5%), TVAzteca (18.3%) and Multimedios (27.8%) were analyzed. Both media were chosen because, while television is the prominent media used in Mexico to follow the development of election campaigns (Montaño, 2009), the press continues to be the media with exceptional ability to establish thematic agenda, playing a leading role in the democratic development of the country (Muñiz, 2015).

The news stories corpus was established from a random sampling of the election campaign over the course of three months, selecting the news stories published every 4 days of the campaign. These ranged from March 6, the start of the campaign, to June 7, which is the day the elections were held. On the selected dates, all the published news stories related to the election campaign analyzed were collected. The search process resulted in the detection of 655 informative notes or units of analysis, 351 corresponded to television and 304 belonged to the press.

Code book

The codebook developed for the content analysis included the following study variables grouped in different sections:

Strategic game frame. Considering previous studies (Aalberg et al., 2012; Cappella & Jamieson, 1997; Dimitrova & Strömbäck, 2012; Elenbaas & de Vreese, 2008; Muñiz, 2015), a scale of five items was used to measure the presence of strategic game frame within the news stories. It was assessed whether the note indicated, mentioned or did (1) or did not include (0) aspects such as "metaphors associated with sports, competition or war" or whether it "provide[d] opinions, surveys and/or public and citizenship opinion states towards politicians, parties, election campaign, affairs, etc." The internal consistency of the scale was low for television (a = .52) and press (a = .53), but in line with previous studies (e.g., Muñiz, 2015).

Issue frame. From the previous studies (Aalberg et al., 2012; Cappella & Jamieson, 1997; Dimitrova & Strömbäck, 2012; Elenbaas & de Vreese, 2008; Muñiz, 2015), a scale of five items was used to measure the presence of issue frame within the news. It was assessed whether the note indicated, mentioned or addressed (1) or not (0) aspects such as "problems and/or solutions on certain political proposals, public policies, legislation, legislative proposals, etc." or the "politicians' stance or statements about substantive policy issues". The internal consistency of the scale was acceptable for television (a = .64), but low for the press (a = .43), although it was a value in line with previous studies (e.g., Muñiz, 2015).

Conflict frame. We also evaluated the presence of the conflict frame, based on the original proposal by Semetko and Valkenburg (2000) and in the Spanish version used, among others, by Muñiz (2011). In particular, the news frame was coded by a scale of three items about whether the story was (1) or was not (1) alluded or referred to: "certain disagreement between political parties, individuals, groups, institutions or countries," "two or more different postures around the issue or problem addressed" or to "a political party, individual, group, institution or country making any kind of objection to another political party, individual, group, institution or country" The internal consistency of the scale was high for both television (a = .74) and press (a = .75), with values similar to those obtained in previous studies (Dimitrova & Strömbäck, 2012; Semetko & Valkenburg 2000).

Debate and political agreement frame. In contrast to the existence of conflict, which indicates the presence of confronted positions and even dispute between actors, the possible existence of a news frame that make known the existence of debates on proposals that resulted in political agreements was considered. In this sense, for the present study a four-item scale was elaborated to evaluate whether the narrative does (1) or does not (0) mention or refers to the following aspects: "the text emphases the debate between political actors on a specific subject or issue"; "the text presents political decision-making as an agreement between actors"; "the text emphases the agreement reached by actors after a negotiation around a narrated decision"; and "the text presents the political decisions making such as listening to each other, mutual understanding, etc." The factor analysis carried out with the four items converged on one component, in both television, KMO = .756, x2 (6, N = 351) = 567,140, p < .001, and press, KMO = .647, X2 (6, N = 304) = 383,784, p < .001. The scale also presented good internal consistency in television (a = .79) and acceptable in press (a = .67).

Coding and Reliability of the Study

Ten undergraduate and graduate students, collaborators of the Political Communication Laboratory (LACOP) of Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, participated in the codification and recording of the units of analysis. In total, two groups of five people were integrated to analyze press and TV news stories separately. As a preliminary step, all of them were trained in the use of developed codebook and had several training tests and a pilot test with 27 randomly collected campaign news stories. Once the full coding was completed, a new analysis was carried out on 93 notes, representing 14.20% of the sample (35 television and 58 press), randomly selected from those composing the initial total sample in order to calculate the reliability or intercoder reliability of the process. The mean agreement value calculated with the Krippendorff alpha formula was .85, resulting in an alpha value of .94 on television and .75 in the press, which implied a high level of agreement between the coders (Neuendorf, 2012).

Results

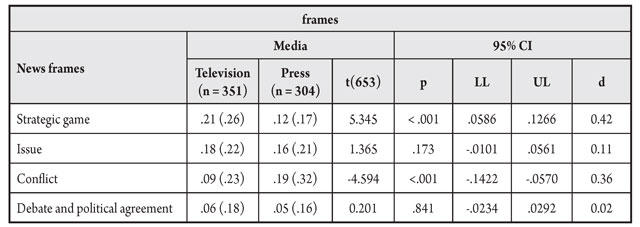

In a first phase of analysis of the results, the use of the different news frames during the election campaign between both media studied, television and the press, was compared (see Table 1). The findings showed a statistically significant difference for the use of strategic game frame, t(653) = 5,345, p <.001, d = 0.42, 95% CI [.0586, .1266]. In this respect, it was observed that television was the media that sensibly made greater use of this frame to make the informative treatment of the election campaign (M = .21, DE = .26), compared to the press (M = .12, DE = .17). Meanwhile, a statistically significant difference among the use of the conflict frame, t (653) = -4.594, p < .001, d = 0.36, 95% IC [-.1422, -.0570] was also observed. In this sense, it was detected that the presence of the conflict treatment in the coverage of the election campaign by the press (M = .19, DE = .32) was clearly greater than that of television (M = .09, DE = .23). Regarding the remaining news frames, no statistical differences were observed between the two media in terms of their use, either for the issue frame, t (653) = 1.365, p = .173, d = 0.11, 95% CI [.0101, .0561], or for debate and political agreement news frame, t (653) = 0.201, p = .841, d = 0.02,, 95% CI [-.0234, .0292].

Table 1. Mean differences between media regarding the use of different news frames

Note: N = 655. All news frames

had a theoretical range of variation between 0 (no presence) and 1 (high

presence). Standard deviations are expressed in brackets. CI = Confidence

Interval; LL = Lower Limit; UL = Upper Limit.

Source: Own elaboration.

For its part, the second research question addressed the moderating effect of time, in this case represented by the date of publication, regarding the use of each news frame by both type of media analyzed in their news stories. In order to carry out this analysis, the publication date variable was converted into an ordinal variable where each date was converted into an integer value between 1 and 24, so that could be observed the moderation effect of the variable over time. To achieve this analysis, the macro PROCESS for SPSS created by Hayes (2013) was used, which allows calculating the main effect of the independent or predictor variable on the dependent or criterion variable (effect b1), the main effect of the moderator variable on the dependent variable (effect b2), and the interaction effect of the independent and moderating variables on the dependent variable (effects b3). Specifically, model 1 was used with a bootstrapping of 10,000 samples to determine the three effects described above. In addition, the date of the news item publication was divided into three stages, following the pick-a-point approach, which establishes three cut-off points from the mean and +/- 1 standard deviation. In this way, the result is a variable with three groups, corresponding to the initial, intermediate and final stages of the election campaign.

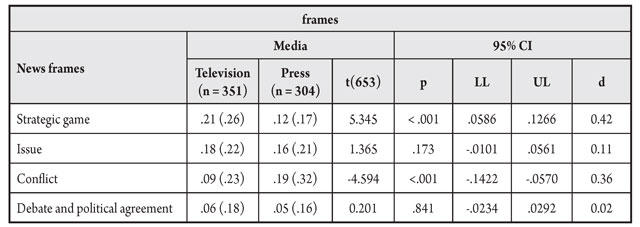

First of all, the effect of time moderation on the strategic game frame use by both media was calculated. The results showed that the model was statistically significant, F(3, 651) = 37.232, p < .001, and, together, they accounted for 14.64% of the variance—i.e., the use of the news frame. A main effect of the media was observed on the use of the news frame, Bmedia = .09, SE = .03, p = .010, 95% CI [.0203, .1522], in line with what was found in the comparison of means previously made at the beginning of the study. A main effect in publication time on the use of the frame was also detected, Bstage = .01, SE = .001, p < .001, 95% CI [.0040, .0083], which shows how, while campaign was advancing, the use of the strategic game frame was increasing. Finally, we also detected an interaction effect between both variables, where BmediaXstage = -.01, SE = .002, p < .001, 95% CI [-0173, -.0087]. Specifically, during the first stage of the election campaign, there were no differences between the media: B = .01, p = .680. However, throughout the rest of campaign, television tended to use to a greater extent the strategic game frame, both at the middle (B = -0.9, p < .001), and the end of the campaign (B = -19, p < .001), as seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Moderation effect of campaign stage on the use of strategic game frame by the media

Source: Own elaboration.

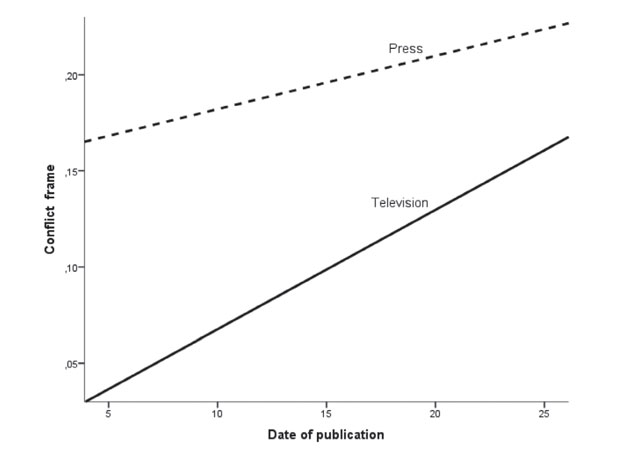

Moreover, no significant effects were found for the use of the issue frame, which was F(3, 651) = 1.095, p = .351. Therefore, it could be concluded that the presence of this treatment was analogous in both media throughout the course of the campaign. However, it was observed that the model for the explanation of the conflict frame was statistically significant, being F(3, 651) = 11.396, p < .001, and that it explained 4.99% of the variance. In this sense, the use of the news frame varied according to the analyzed media outlet (i.e., Bmedia = .15, SE = .04, p < .001, 95% CI [.0622, .2354]), and date of publication (i.e., Bstage =. 01, SE = .001, p = .002, 95% CI [.0017, .0073]), increasing its presence in media throughout the election campaign. However, time did not show a moderation effect across the use of the frames in both media outlets, being BmediaXstage = 01, SE = .003, p = .232, 95% CI [-0091, .0022]. It was observed, therefore, that both in the first stage of the campaign (B = .13, p < .001), as in the intermediate (B = .10, p < .001) and the final stages (B = .08, p = .013), there was a prevalence of conflict frame in the press versus television (See Figure 2).

Figure 2. Moderation effect of campaign stage in the use of conflict frame by the media

Source: Own elaboration.

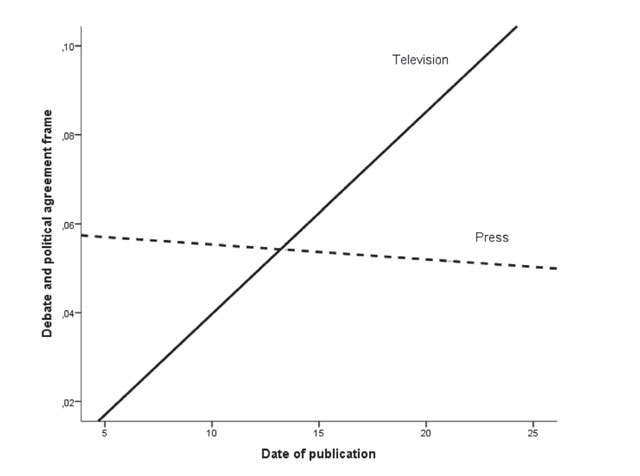

Finally, and regarding the explanatory model proposed for the use of the debate and political agreement news frame, the results were statistically significant: F(3, 651) = 5.205, p = .002, R2 = .0234. Although the analysis showed that the use of the frame does not present any variation in function of the analyzed media, being Bmedia = .001, p = .914, as was detected in the first test. However, it was possible to observe statistically significant differences according to the time of publication of the news: Bstage = .002, SE = .001, p = .010, 95% CI [.0098, .0006]. In this sense, the presence of debate and political agreement frame in the news increased as the election campaign progressed. In addition, the time factor moderated the use of the frame by the media, being BmediaXstage = -.005, SE = .002, p = .006, 95% CI [-.0084, -.0014]. Thus, we observed a trend difference in the first stage between media regarding the use of the frame, slightly headed by the press, with B = .04, p = .060. In the intermediate stage of campaign, no differences were observed in the use of the news frame, with B = -.001, p = .914, while at the end of the campaign there were statistically significant differences between the media outlets at B = -0.4, p = .044. At this moment, television outpaced the press focusing on debate and political agreement (See Figure 3).

Figure 3. Moderation effect of campaign stage in the use of debate and political agreement frame by the media

Source: Own elaboration.

Discussion and Conclusions

This paper aims to analyze the strategies of framing followed by the media— in this case, television and press—during the election campaigns. For that purpose, the study worked with the news frames traditionally used in the literature that analyzed the electoral coverage made by the news stories, such as the strategic game frame (e.g., Aalberg et al., 2012; de Vreese, 2005; Dimitrova & Kostadinova, 2013, Schmuck et al., 2017), the issue frame (e.g., Muñiz, 2015; Pedersen, 2012; Rhee, 1997), and the conflict frame (e.g., de Vreese, 2005; Lengauer et al., 2012; Strömbäck & Luengo, 2008). As a theoretical contribution of this article, we proposed the creation of a new news frame that reflects the debate or political agreement, the use of which was also compared in both media. For this end, this news frame was operationalized from the theoretical proposals previously made by authors such as Lengauer et al. (2012) or Sevenans and Vliegenthart (2016).

The results allowed us to verify the first hypothesis, reaching the conclusion that strategic game frame has a greater presence in the coverage of the election campaign carried out by television than the press. This result is similar to previous studies in different national contexts (de Vreese & Semetko, 2002; Elenbaas & de Vreese, 2008; Schmuck et al., 2017; Shehata, 2014). Nevertheless, it is an important contribution since, as was observed in the literature review, few compared studies between media during the same election have been done. Also, it is well known that television plays a particularly important role in electoral coverage, as it is one of the most adopted mass media selected by broader audiences to get informed about elections (Lozano et al., 2012; Montaño, 2009). Therefore, this finding reveals possible implications that this treatment can have for those who follow the campaign in this media outlet, which is usually linked to the development of negative attitudes (de Vreese & Semetko, 2002; Elenbaas & de Vreese, 2008).

The second hypothesis stated that the issue frame would have a greater presence in the election campaign coverage on the press versus television, in line with the results detected by Shehata (2014). The results of the study, however, did not allow us to verify the hypothesis, while no statistical differences between the two media outlets were detected. While it is true that the descriptive data show a greater level of use of this frame within the news stories of the press than the others contemplated in the work, in the comparison between media outlets the press made a similar use of this approach. This implies that it cannot be assumed that different audiences, consumers of different media such as television and press, have had access to an information more or less oriented to the debate on the political issue and its edges, regardless of the media outlet consumed (Aalberg et al., 2012; Dimitrova & Kostadinova, 2013; Muñiz, 2015; Pedersen, 2012; Rhee, 1997). Therefore, it is concluded that there is a more strategic coverage on television, but with similar levels of presentation of programmatic proposals in both media outlets, which in general terms was a less adopted approach in the coverage of the election campaign.

Furthermore, the use study of the conflict frame was raised from the hypothetical proposition that this approach would dominate in the coverage made by the press, compared to television. The findings allow us to verify this hypothesis, in line with findings presented in previous studies on the use of this news frame (Berganza, Arcila, & de Miguel Pascual, 2016; Schuck et al., 2013). It is therefore proved that the coverage of Mexican election campaigns, as well as those of other contexts previously reviewed, is also constructed from a strong emphasis on the conflict framing, that is, the confrontation and reproach among the different actors (de Vreese et al., 2001; Lengauer et al., 2012; Strömbäck & Luengo, 2008). The media seem to keep giving a greater presence to the negativity in the exhibition of the campaign events, as happened in previous Mexican national court elections (Freidenberg & González Tule, 2009; Lozano et al., 2012; Muñiz, 2015). However, and as has been suggested by previous political communication studies, when faced with this kind of coverage, which is negative to an extent, it is possible to propose a confrontation seeking an agreement instead.

This was the idea that led to the operationalization of a news frame that measured the degree in which media outlets emphasized debate and political agreement among the actors of an election campaign. Following previously proposals made by researchers (Lengauer et al., 2012; Sevenans & Vliegenthart, 2016; Schuck, 2017; Schuck et al., 2016), a scale was produced that showed good performance to measure the coverage of politics as a debate that seeks to solve problems through consensus and agreement between actors. In addition, and in response to the first question of investigation, no statistical differences were detected between the two media outlets regarding the use of this news frame. It also highlights the comparatively less used approach during the electoral process, which reflects how the campaign is still seen by the media in general as a battlefield and confrontation—where personal allegations and accusations, not the proposals, stand out—, rather than as a stage for dialogue and agreement, in a deliberative context.

Finally, the second research question about whether the election campaign throughout its different stages does or does not generated a moderation effect on the use of the different media outlets, television and press. Findings are interesting and open a promising line of research, as few investigations have so far studied the longitudinal effect generated by the campaign itself in framing strategies followed by the media outlets (Muñiz, 2015; Schuck et al., 2013). Overall, the calculated moderation tests produced results that demonstrate how the course of the campaign moderated the use of most part of the news frames contemplated in the study. In all cases, except for the issue frame, effects of the variables included in the studies were observed. This shows how the attention on candidates' programmatic proposals was less interesting for the media during all stages of the election campaign, and they however focused on campaign strategies, confrontation or conflict, and the game of winners and losers.

The results reveal that television was the media outlet with a greater extent of treatment differences observed across the election campaign based on how it happened during the different stages. In the case of the press, this media outlet was predominant in the use of the conflict frame, and it remained constant throughout the electoral process, tending to increase as time went by. However, television significantly increased the use of the remaining frames throughout the election campaign. Both strategic game and conflict frames such as debate and political agreement frame were approaches that tended to grow in television coverage as the campaign progressed and, above all, entered the final and decisive phase of the electoral process. Results show the potential that television, as a still massive media, can have in the configuration of the collective framing shared by much society and related to what happens during the campaigns. Moreover, and regarding the establishment of the approaches that help citizens to understand the election campaign, public opinion is shaped, and the subsequent decision-making and political behavior is developed.

References

Aalberg, T., Strömbäck, J. & de Vreese, C. H. (2012). The framing of politics as strategy and game: A review of concepts, operationalizations and key findings. Journalism, 13(2), 162-178. doi: 10.1177/1464884911427799

Aruguete, N. (2010). Los encuadres noticiosos en los medios argentinos. Un análisis de la privatización de ENTEL. América Latina Hoy, 54, 113-137.

Bartholomé, G., Lecheler, S. & de Vreese, C. H. (in press). Towards a typology of conflict frames. Substantiveness and interventionism in political conflict news. Journalism Studies. doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2017.1299033

Berganza, R. (2008). Medios de comunicación, espiral del cinismo y desconfianza política. Estudio de caso de la cobertura mediática de los comicios electorales europeos, ZER, 13(25), 121-139.

Berganza, R., Arcila, C. & de Miguel Pascual, R. (2016). La negatividad en las informaciones políticas de los medios españoles. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 71, 160-178. doi: 10.4185/RLCS-2016-1089

Berumen, G. Y. & Medellín, L. N. (2016). Marketing de los candidatos a la gubernatura de Nuevo León en las redes sociales durante el proceso electoral de 2015. Apuntes Electorales, (54), 57-90.

Boomgaarden, H. G. (2017). Media representation: Politics. In P. Rössler, C. A. Hoffner & L. van Zoonen (Eds.), The international encyclopedia of media effects (pp. 1-13). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. doi: 10.1002/9781118783764.wbieme0149

Cappella, J. N. & Jamieson, K. H. (1997). Spiral of cynicism: The press and the public good. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

D'Angelo, P. (2002). News framing as a multiparadigmatic research program: A response to Entman. Journal of Communication, 52(4), 870-888. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2002.tb02578.x

de Vreese, C. H. (2003). Framing Europe: Television news and European integration. Amsterdam: Aksant Academic Publishers.

de Vreese, C. H. (2004). The effects of frames in political television news on issue interpretation and frame salience. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 81(1), 36-52. doi: 10.1177/107769900408100104

de Vreese, C. H. (2005). The spiral of cynicism reconsidered. European Journal of Communication, 20(3), 283-301. doi: 10.1177/0267323105055259

de Vreese, C. H. (2012). New avenues for framing research. American Behavioral Scientist, 56(3), 365-375. doi: 10.1177/0002764211426331

de Vreese, C. H. (2014). Mediatization of news: The role of journalistic framing. In J. Strömbäck & F. Esser (Eds.), Mediatization of politics. Understanding the transformation of western democracies (pp. 137-155). London: Palgrave Macmillan. doi: 10.1057/9781137275844_8

de Vreese, C. H. & Semetko, H. A. (2002). Cynical and engaged: Strategic campaign coverage, public opinion, and mobilization in a referendum. Communication Research, 29(6), 615-641. doi:10.1177/009365002237829

de Vreese, C. H., Peter, J. & Semetko, H. A. (2001). Framing politics at the launch of the Euro: A cross-national comparative study of frames in the news. Political Communication, 18(2), 107-122. doi: 10.1080/105846001750322934

Dimitrova, D. V. & Kostadinova, P. (2013). Identifying antecedents of the strategic game frame. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 90(1), 75-88. doi: 10.1177/1077699012468739

Dimitrova, D. V. & Strömbäck, J. (2012). Election news in Sweden and the United States: A comparative study of sources and media frames. Journalism, 13(5), 604-619. doi: 10.1177/1464884911431546

Elenbaas, M., & de Vreese, C. H. (2008). The effects of strategic news on political cynicism and vote choice among young voters. Journal of Communication, 58(3), 550-567. doi: 10.1111/j.14602466.2008.00399.x

Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication, 43(4), 51-58. doi: 10.1111/ j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x

Freidenberg, F. & González Tule, L. (2009). Estrategias partidistas, preferencias ciudadanas y anuncios televisivos: un análisis de la campaña electoral mexicana de 2006. Política y Gobierno, 16(2), 269-320.

Gerth, M. A. & Siegert, G. (2012). Patterns of consistence and constriction: How news media frame the coverage of direct democratic campaigns. American Behavioral Scientist, 56(3), 279-299. doi: 10.1177/0002764211426326

Gronemeyer, M. E. & Porath, W. (2017). Framing Political News in the Chilean Press: The Persistence of the Conflict Frame. International Journal of Communication, 11, 2940-2963.

Hänggli, R. & Kriesi, H. (2012). Frame construction and frame promotion (Strategic framing choices). American Behavioral Scientist, 56(3), 260-278. doi: 10.1177/0002764211426325

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Nueva York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Lengauer, G., Esser, F. & Berganza, R. (2012). Negativity in political news: A review of concepts, operationalizations and key findings. Journalism, 13(2), 179-202. doi: 10.1177/1464884911427800

Lozano, J. C., Cantú, J., Martínez, F. J. & Smith, C. (2012). Evaluación del desempeño de los medios informativos en las elecciones de 2009 en Monterrey. Comunicación y Sociedad, (18), 173-197.

Matthes,J. (2009). What's in a frame? A content analysis of media framing studies in the world's leading communication journals, 1990-2005. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 86(2), 349-367. doi: 10.1177/107769900908600206

Matthes, J. (2012). Framing politics: An integrative approach. American Behavioral Scientist, 56(3), 247-259. doi: 10.1177/0002764211426324

Montaño, M. (2009). La televisión y las campañas electorales en México. ¿Control estatal o control mediático? Acta Republicana. Política y Sociedad, 8(8), 63-74.

Muñiz, C. (2011). Encuadres noticiosos sobre migración en la prensa digital mexicana. Un análisis de contenido exploratorio desde la teoría del framing. Convergencia, 18(55), 213-239.

Muñiz, C. (2015). La política como debate temático o estratégico. Framing de la campaña electoral mexicana de 2012 en la prensa digital. Comunicación y Sociedad, (23), 67-95.

Muñiz, C. & Ramírez, J. (2015). Los empresarios frente al narcotráfico en México. Tratamiento informativo de las reacciones empresariales ante situaciones de violencia e inseguridad. Estudios sobre el mensaje periodístico, 21(1), 437-453. doi: 10.5209/rev-ESMP.2015. v21.n1.49104

Neuendorf, K. A. (2012). The content analysis guidebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Neuman, W. R., Just, M. R., & Crigler, A. N. (1992). Common knowledge. News and the construction of political meaning. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Nohlen, D. (1998). Sistemas electorales y partidos políticos (2nd ed.). Ciudad de México: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Nuncio, A. (2015). Nuevo León: entre la insularidad y el bipartidismo. El Cotidiano, (193), 23-36.

Pedersen, R. T. (2012). The game frame and political efficacy: Beyond the spiral of cynicism. European Journal of Communication, 27(3), 225-240. doi: 10.1177/0267323112454089

Price, V., & Tewksbury, D. (1997). News values and public opinion: A theoretical account of media priming and framing. In G. A. Barnett & F. J. Boster (Eds.), Progress in the communication sciences (pp. 173- 212). New York, NY: Ablex.

Rhee, J. (1997). Strategy and issue frames in election campaign coverage: a social cognitive account of framing effects. Journal of Communication, 47(3), 26-48. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1997.tb02715.x

Rinke, E. M., Wessler, H., Löb, C. & Weinmann, C. (2013). Deliberative qualities of generic news frames: Assessing the democratic value of Strategic Game and Contestation Framing in Election Campaign Coverage. Political Communication, 30(3), 474-494. doi: 10.1080/10584609.2012.737432

Schmuck, D., Heiss, R., Matthes, J., Engesser, S. & Esser, F. (2017). Antecedents of strategic game framing in political news coverage. Journalism, 18(8), 937-955. doi: 10.1177/1464884916648098

Schuck, A. R. T. (2017). Media malaise and political cynicism. In P. Rõssler, C. A. Hoffner, & L. van Zoonen (Eds.), The international encyclopedia of media effects (pp. 1-19). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, Inc. doi: 10.1002/9781118783764.wbieme0066

Schuck, A. R. T., Boomgaarden, H. G. & de Vreese, C. H. (2013). Cynics all around? The impact of election news on political cynicism in comparative perspective. Journal of Communication, 63(2), 287-311. doi: 10.1111/jcom.12023

Schuck, A. R. T., Vliegenthart, R., Boomgaarden, H. G., Elenbaas, M., Azrout, R., van Spanje, J. & de Vreese, C. H. (2013). Explaining campaign news coverage: How medium, time, and context explain variation in the media framing of the 2009 European parliamentary elections. Journal of Political Marketing, 12(1), 8-28. doi: 10.1080/15377857.2013.752192

Schuck, A. R. T., Vliegenthart, R. & de Vreese, C. H. (2016). Who's afraid of conflict? The mobilizing effect of conflict framing in campaign news. British Journal of Political Science, 46(1), 177-194. doi: 10.1017/S0007123413000525

Semetko, H. A. & Valkenburg, P. M. (2000). Framing European politics: A content analysis of press and television news. Journal of Communication, 50(2), 93-109. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2000.tb02843.x

Sevenans, J. & Vliegenthart, R. (2016). Political agenda-setting in Belgium and the Netherlands. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 93(1), 187-203. doi: 10.1177/1077699015607336

Shehata, A. (2014). Game frames, issue frames, and mobilization: Disentangling the effects of frame exposure and motivated news attention on political cynicism and engagement. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 26(2), 157-177. doi: 10.1093/ijpor/edt034

Strömbäck, J. & Dimitrova, D. V. (2011). Mediatization and media interventionism: A comparative analysis of Sweden and the United States. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 16(1), 30-49. doi: 10.1177/1940161210379504

Strömbäck, J. & Luengo, O. G. (2008). Polarized pluralist and democratic corporatist models: A comparison of election news coverage in Spain and Sweden. International Communication Gazette, 70(6), 547-562. doi: 10.1177/1748048508096398

Valkengburg, P. M., Semetko, H. A. & de Vreese, C. H. (1999). The effects of news frames on readers' thoughts and recall. Communication Research, 26(5), 550-569. doi: 10.1177/009365099026005002

Zillmann, D., Chen, L., Knobloch, S. & Callison, C. (2004). Effects of lead framing on selective exposure to internet news reports. Communication Research, 31(1), 58-81. doi: 10.1177/0093650203260201