|

Artículos Persuading with Narratives Against Gender Violence. Effect of Similarity with the Protagonist on Identification and Risk-PerceptionPersuasión con narrativas contra la violencia de género. Efectos de la similitud con el protagonista en la identificación y la percepción de riesgosPersuasão com narrativas contra a violência de gênero. Efeitos da semelhança com o protagonista na identificação e a percepção de riscos |

Juan José Igartua1

Daniela Fiuza2

1 orcid.org/0000-0002-9865-2714. Universidad de Salamanca, España. jigartua@usal.es

2 orcid.org/0000-0002-0379-5545. Universidad de Salamanca, España.

Recibido: 2017-04-03

Enviado a pares: 2017-06-07

Aprobado por pares: 2017-07-12

Aceptado: 2017-08-15

Para citar este artículo / to reference this article / para citar este artigo: Igartua, J. J. y Fiuza, D. (2018). Persuading with Narratives Against Gender Violence. Effect of Similarity with the Protagonist on Identification and Risk-Perception. Palabra Clave, 21(2), 499-523. DOI: 10.5294/pacla.2018.21.2.10

Abstract

This study focuses on analysis of the factors that can increase the persuasive effectiveness of information campaigns using narratives. An experiment was carried out in which similarity with the protagonist was manipulated in a video about a victim of gender violence. The protagonist was portrayed as living in Spain, and she was said to be Spanish (high similarity) or Argentinian (low similarity). The participants (75 Spanish women) then filled out a questionnaire with measures about emotional impact, identification with the protagonist, and risk perception about becoming a victim of abuse. Results showed that similarity with the protagonist has an indirect influence on risk perception through negative emotions and identification.

Keywords : Persuasion; communication psychology; domestic violence (Source: Unesco Thesaurus).

Resumen

Este estudio se enfoca en el análisis de los factores que pueden aumentar la efectividad persuasiva de las campañas de información por medio de narrativas. Se realizó un experimento en el que la similitud con el protagonista se manipuló en un video sobre una víctima de violencia de género. Se describió a la protagonista como si viviera en España y se dijo que era de nacionalidad española (gran similitud) o argentina (baja similitud). A continuación, las participantes (75 mujeres españolas) respondieron un cuestionario con medidas sobre el impacto emocional, la identificación con el protagonista y la percepción del riesgo de convertirse en víctima de abuso. Los resultados mostraron que la similitud con la protagonista tiene una influencia indirecta en la percepción del riesgo a través de las emociones negativas y la identificación.

Palabras clave: Persuasión; psicología de la comunicación; violencia doméstica (Fuente: Tesauro de la Unesco).

Resumo

Este estudo se enfoca na análise dos fatores que podem aumentar a eficácia persuasiva das campanhas de informação através de narrativas. Realizou-se um experimento em que a semelhança com o protagonista foi manipulada em um vídeo sobre uma vítima de violência de gênero. Descreveu-se a protagonista como se esta morasse na Espanha, e foi dito que era de nacionalidade espanhola (grande semelhança) ou argentina (baixo nível de semelhança). A seguir, as participantes (75 mulheres espanholas) responderam um questionário com medidas sobre o impacto emocional, a identificação com o protagonista e a percepção do risco de tornar-se vítima de abuso. Os resultados revelaram que a semelhança com a protagonista tem uma influência indireta na percepção do risco através das emoções negativas e da identificação.

Palavras-chave: Persuasão; psicologia da comunicação; violência doméstica (Fonte: Tesauro da Unesco).

Introduction

This study focuses on analyzing factors that can increase the persuasiveness of campaigns aimed at confronting social problems (in this case, gender violence), using as reference the ones constructed around a narrative. In this context, by narrative we mean a sequence of events that are causally connected (and are therefore not random), using a series of characters whose experience can serve to teach (Hoeken, Kolthoff, & Sanders, 2016). A narrative always provides information (and implicit or explicit arguments) based on which individuals can change or adapt their beliefs, attitudes and behaviors. Research into narrative persuasion studies the processes or mechanisms that explain how narratives can change attitudes, beliefs or behaviors (de Graaf, Hoeken, Sanders, & Beentjes, 2012; Green & Brock, 2000; Hoeken & Fikkers, 2014; Igartua & Barrios, 2012). A meta-analysis review has shown that narratives have significant effects on attitudes, beliefs, behavioral intention and behavior (Braddock & Dillard, 2016).

One of the main fields where this line of research is being applied is in health communication from the perspective of entertainment-education (de Graaf, Sanders, & Hoeken, 2016; Igartua & Vega, 2016; Moyer-Gusé, Chung, &Jain, 2011; Robinson & Knobloch-Westerwick, 2017). Many advertising campaigns (whether commercial or socially-oriented) are based on the construction of narrative messages, as in the use of publicity genres called "testimonials," "slice of life" and other story-based advertisements. Thus, it is important to learn which factors in the design of narratives for the prevention or awareness-raising of social problems (in this study, gender violence) increase their persuasive impact and, therefore, their effectiveness as tools of media intervention. In this study we address the variables related to the construction of characters (in particular, the similarity between character and audience), reception processes (identification with characters and emotions), and individual differences (modern racism).

Similarity, Identification with Characters, and Persuasive Impact

Characters are a basic ingredient in any narration, and therefore their design, characteristics, or attributes can condition reception processes and persuasive impact (Moyer-Gusé, 2008). In the field of narrative persuasion, it has been shown that identification with characters plays an important mediating role: For a narrative to cause a persuasive impact there must be a high identification with the characters involved (de Graaf et al., 2012; Hoeken & Fikkers, 2014; Igartua & Barrios, 2012; Igartua & Vega, 2016). In this context, identification with characters is a cognitive-affective process that takes place during reception (reading, viewing) of the narrative message, and that is linked to perspective-taking or cognitive empathy (putting oneself in the shoes of the character), emotional empathy (feeling the same emotions as the character), and the temporary loss of self-awareness (the receiver of the narrative imagines being the character, taking on his or her identity, and becoming merged with the character) (Cohen, 2001; Igartua & Barrios, 2012; Moyer-Gusé, 2008).

Previous research has shown that the characteristics of characters condition reception processes (such as appraisal of the character, emotions and identification) (Hoeken & Sinkeldam, 2014), that identification plays an important role in emotional activation (the greater the identification, the greater the emotional impact) (Hoeken, Kolthoff, & Sanders, 2016), and that, in addition, it is an important mechanism in explaining the impact of narratives on attitudes (together with emotions) (de Graaf et al., 2012; Igartua & Vega, 2016).

To date, there has been little research into the factors involved in the construction of characters that can increase identification and, indirectly, persuasive impact. One line of research in this field is related to the effect that similarity between the protagonist ofthe narrative and the audience has on identification, and on the persuasive effectiveness of the story (Chen, Bell, & Taylor, 2016; de Graaf, 2014; Hoeken, Kolthoff, & Sanders, 2016). Similarity describes a process through which a message receiver assesses the extent to which he or she shares certain traits with the message protagonist. Similarity can be based on objective traits (such as demographic aspects, gender, or nationality) but also on psychological or subjective characteristics (such as personality, beliefs, opinions, or values). It is assumed that both perceived similarity and similarity in objective attributes increase identification and, indirectly, affect attitudes. In fact, it has even been maintained that similarity is a prerequisite for identification with a character, since identification involves a merging ofidentities (Cohen, 2001). In other words, it is assumed that, the greater the similarity to a character, the greater the identification, leading to our first hypothesis:

H1: Similarity with the protagonist of an awareness-raising narrative on gender violence will cause greater identification with that character.

Previous research into the effect of similarity on persuasive impact has been carried out using written stories or short stories. Similarity has been manipulated experimentally by varying the characteristics of the main character in the story and at the same time taking into account the situation or characteristics of the study participants or receivers (Chen et al., 2016; de Graaf, 2014; Hoeken et al., 2016). For example, in the study carried out by de Graaf (2014), information about where the main character of the narrative lived was manipulated (with her parents or in a student dorm); at the same time, the participants were asked with whom they lived. High similarity was assumed if the place of residence of the character coincided with the place of the residence of the person reading the story. In this case, it can be said that similarity was manipulated in demographic terms (place of residence). The narrative was focused on health topics (the main character had cancer and the narrative described how she faced the disease), and the persuasive objective was to increase risk perception, since risk perception has been considered a determinant factor in preventive or health behavior and can also be considered an indicator ofawareness. In this context, an important effect of the narrative messages used in entertainment-education is that they reduce the perception of invulnerability and, as a result, increase risk perception ("this could happen to me"), which has an influence on intentions of preventive behavior or helps individuals to be alert to situations of risk in the future (Moyer-Gusé, 2008). The results showed that similarity with the character had an influence on perceived similarity and furthermore increased risk perception (de Graaf, 2014). Thus, similarity had an attitudinal effect consistent with the contents of the narrative. Taking these results into account, we postulated the second hypothesis of the study in relation to the effect of similarity on risk perception.

H2: Similarity with the protagonist of an awareness-raising narrative on gender violence will induce a greater perception of the risk of becoming a victim of abuse.

Social Perception of Gender Violence, Immigration, and Modern Racism

Taking research into narrative persuasion as a reference, it is worth positing that, when awareness-raising campaigns are carried out in relation to gender violence using narratives (based on testimonials or slice of life, for example), the messages should have protagonists who produce a high sense of identification among women. In this context, identification can be facilitated when the protagonist of the narrative is perceived as similar by the audience (women in particular, as the potential victims of abuse). In the research carried out for this study, we took into account a demographic aspect to manipulate the similarity experimentally: the nationality of the protagonist of the narrative. There are several lines of research that justify the choice of this characteristic.

The first thing to highlight is that content analysis studies about the reporting of gender violence have shown that this topic is usually associated with immigration. For example, the news may show that foreign women or immigrants are the ones most suffering from gender abuse, or when gender violence is reported, the victim's nationality is stated, indicating whether she is a foreigner or an immigrant (Román, García, & Alvarez, 2011). Thus, the stereotype of gender violence is shown to be something inherent to "other cultures" (Erez, Adelman, & Gregory, 2009; Wright & Benson, 2010). In relation to this, different surveys about the social perception of gender violence carried out in Spain have shown that respondents consider that there are more perpetrators among foreigners than among the Spanish, and they also perceive that foreign women are more vulnerable to gender violence (Meil, 2014). In fact, one of the myths of gender violence is to think that it only occurs in underdeveloped countries (Bosch-Fiol & Ferrer-Pérez, 2012). As a result, it is worth postulating that prejudice against immigrants could interfere in the effectiveness of campaigns against gender violence with immigrant women as protagonists, given that they may stimulate a lower risk perception and cause a lower identification with the victims, especially among individuals who reject immigration more strongly.

In this context, it was found that prejudice against immigrants is associated with more negative attitudes and emotions towards immigrants in everyday situations. It is logical to think that this effect will also manifest in a situation of parasocial intergroup contact, such as when watching a narrative message about gender violence with an immigrant as the protagonist. In fact, it has been pointed out that individuals show ingroup favoritism when choosing the contents of media entertainment: They prefer to consume entertainment products that have characters from their same group (defined by criteria such as gender, age, ethnic origin, or nationality) (Park, 2012).

Prejudice towards immigrants can be conceptualized from several different theoretical perspectives, giving rise to different forms of measurement. In this study we based our research on the concept of modern racism (McConahay, Hardee, & Batts, 1981). Modern racism is a subtle form of prejudice and is linked to ambivalent reactions towards persons of a specific outgroup (in our case, immigrants). On one hand, a person who shows a high level of modern racism thinks that immigrants (or other ethnic minorities) break the rules and values of the host society; in addition, they believe that they "ask for too much"; they think that the government or institutions devote excessive social or economic resources to protect immigrants, that their own group is being ignored or harmed in some way, and therefore they feel a certain resentment towards these groups. For these reasons, modern racism is associated with reactions of mistrust and avoidance of contact with persons of the out-group and also with feeling uncomfortable, insecure, distrustful and less positive about them (Gaertner & Dovidio, 1986).

Research into modern racism and its links to processes of reception and narrative persuasion is scant (Eno & Ewoldsen, 2010; Igartua & Frutos, 2017). Eno and Ewoldsen (2010) observed that individuals' prior level of prejudice towards people of color (measured by the scale of modern racism) influenced how participants interpreted a film with an anti-racist message. Moreover, it has been observed that people with a high level of prejudice (high on the modern racism scale) experienced a lower empathic identification with the immigrant protagonists in films. However, it was also observed that watching a movie with a message of empathy towards immigrants caused greater identification with the immigrant characters, which in turn induced more positive attitudes towards immigration, but this process only took place among individuals with a low or moderate level of modern racism (Igartua & Frutos, 2017). This means that modern racism, as a measure of prejudice towards immigrants, can interfere in reception processes, conditioning narrative persuasion processes. Thus, in the research presented here, it is expected that prejudice towards immigrants (modern racism) will act as a moderating variable: Individuals with greater prejudice towards immigrants will experience greater identification when the protagonist of the message meant to raise awareness of gender violence is presented as Spanish than when she is presented as a foreigner.

H3: Among participants with a low level of modern racism, the similarity will not affect their identification. However, among the participants with a high level of modern racism, the similarity will induce a high identification.

Finally, we postulate a moderated mediation model (Hayes, 2013), which involves simultaneously analyzing the role of modern racism (as moderating variable) and identification with character (as mediating variable) to explain the indirect effect of similarity in the risk perception of becoming a victim of gender abuse.

H4: Similarity with the protagonist of the narrative will stimulate greater identification, which in turn will be associated with a greater risk perception of being a victim of gender abuse; this process, however, will take place only among individuals with a high level of modern racism.

Method

Participants

Seventy-five women participated in the research study. All of them were Spanish university students with a mean age of20.29 (SD = 1.81). Their participation was voluntary and they did not receive any compensation for taking part in the study. We used a convenience sample that is a nonprobability sampling method especially used in experimental research (Hayes, 2005).3

Design and procedure

A random two-group design was chosen, the independent variable being similarity in demographic terms (nationality) with the protagonist of a video narrative (a public service announcement constructed as a narrative that tells the story of Maria, a victim of gender violence) with two conditions: low similarity (the protagonist is presented as an Argentinian woman living in Madrid, and thus a foreign immigrant) or high similarity (the protagonist is presented as a Spanish woman living in Madrid). The manipulation was carried out by editing the video shown to the participants.

The participants were invited to join the study (individually), and once they had agreed, they were randomly assigned to one of the two experimental conditions. Before viewing the video, they had to answer a questionnaire intended to collect information about the following variables: prejudice towards immigrants (modern racism scale), age and nationality (to remove any women who were not Spanish from the study). They were then shown a video (on a laptop) and immediately afterward they were asked to complete a second questionnaire aimed at collecting information about the reception processes (the emotions felt, identification, enjoyment), about the risk perception of becoming a victim of gender violence, and, finally, they were asked if they recalled the nationality of the protagonist.

The video production used was based on an awareness-raising campaign against gender violence and abuse sponsored by the government of Argentina and it showed several explicit situations of gender abuse and violence in a family setting. The video was edited (some dialogues were taken out, some music and subtitles were added) to create versions of the same running time (2 minutes and 5 seconds) where the viewer could read the subtitled dialogue and therefore no Argentinian or Spanish accent would be heard that would condition the reception process. The experimental manipulation involved presenting the following information in text on the screen to introduce the protagonist (duration: 8 seconds): "Maria, Spanish [Argentinian], 43 years old. She has been living in Madrid for 6 years. She is the mother of 3 children and has been married to Juan, her abuser, for 15 years. This is her story..." After introducing the protagonist, the images move ahead with scenes of violence perpetrated by Maria's husband, Juan. The video images are accompanied by music with a sad tone and a series of subtitles with expressions by Juan and by Maria. The texts were the same in the two experimental conditions. The public service announcement ends with an image in which the protagonist is seen unfolding a piece of paper with a helpline telephone number on it and the following written message: "Another kind of life is possible; we all have the right to live without violence; report him!"

The dramatic element (increased by the soundtrack) was meant to cause an emotional impact, to have the participants put themselves in the victim's shoes (Maria), and to induce them to think that Maria's situation could happen to anyone (that is, to activate risk perception) and that, therefore, they should be prepared and know how to act. Indeed, the end of the short film contains a message of hope and proposes a clear idea with respect to gender violence, encouraging women to report it and change their lives.

Measures

Prejudice towards immigrants. This variable was measured using the Modern Racism Scale by McConahay et al. (1981). The scale consists of 10 items (e.g., "in recent years, immigrants have done better economically than they deserve"; ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree). A modern racism index was created by adding up all the items after recoding two reverse item, and a Cronbach's alpha of .84 was obtained (M = 2.32, SD = 0.86).

Negative emotions. Participants were asked: "How did you feel while watching the video? Think of the different things that happened in the video you have just watched and indicate, on a scale of 0 (nothing) to 4 (very much), how much you experienced the following feelings." The scale was comprised of 10 items referring to negative emotions (e.g., anger, disgust, sadness; fear; a = .78; M = 1.86, SD = 0.69).

Enjoyment. The participants were asked the following: "How would you assess, overall, the video you've just watched? (ranging from 1 = I didn't like it at all, to 10 = I liked it a lot; M = 6.10, SD = 2.11)."

Identification with the protagonist. This was evaluated with a scale consisting of 11 items (Igartua & Barrios, 2012), designed to measure retrospectively the participant's identification with the protagonist of the public service announcement, Maria (e.g., "I experienced Maria's emotional reactions in myself"; ranging from 1 = not at all, to 5 = a lot). An index of identification with Maria was created based on calculating the average of the scores in the 11 items (a = .87; M = 3.17, SD = 0.72).

Risk perception with respect to gender violence. A three-item scale was used to assess this factor: "How likely do you think it is that you could personally find yourselfinvolved in a situation of gender violence?" "How likely do you think it is that a person similar to you (in age, educational level, social class) could find herself involved in a situation of gender violence?" And, "How likely do you think it is that a person from your surroundings could find herself involved in a situation of gender violence? (ranging from 1 = not at all, to 10 = very)." Principal components factor analysis showed that the three variables considered measured a single latent factor that explained 70.40 % of the variance. We therefore created a risk perception index of falling victim to abuse based on calculating the average of the scores in the three items (a = .78; M = 4.75, SD = 1.96).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

First, we checked whether significant differences existed between the participants in the two experimental conditions in the age, enjoyment and negative emotions. No statistically significant differences were observed in age (t(73) = -0.72, p = .468) and on enjoyment (t(71) = 1.49, p = .140). However, similarity with the protagonist had a statistically significant effect on the negative emotions (t(70) = 2.24, p < .028). The participants who viewed the public service announcement to raise awareness of gender violence in which the protagonist was said to be Spanish experienced more intense negative emotions (M = 2.02, SD = 0.62) compared to the participants who watched the video in which the victim of gender abuse was presented as an immigrant (M = 1.67, SD = 0.72).

Finally, we tested whether the experimental manipulation had been successful, that is, whether the participants' recall ofMaria's nationality was consistent with the version of the video they were shown. Statistically significant differences were found in their recall of the protagonist's nationality (x2 (2, N = 75) = 48.36,p < .001). Among the participants who viewed the video in which the woman was presented as Spanish, 60 % correctly identified her nationality. In the case of the participants who were told that the woman was Argentinian, 77.1 % correctly recalled this fact. Overall, it can be said that the experimental manipulation worked, given that the information on the woman's nationality (only presented at the beginning of the video for 8 seconds) was recalled by most of the participants and in a way consistent with the version they had been randomly assigned.

Hypothesis 1: Effect of similarity on identification with the protagonist

The effect of similarity on identification with the protagonist was not statistically significant (t(69) = 0.09, p = .926). Identification with the protagonist was similar both when she was presented as being Spanish (M = 3.17, SD = 0.69) and when presented as Argentinian (M = 3.16, SD = 0.77). Further, we performed a mediation analysis (with PROCESS macro, model 4; Hayes, 2013), and it was found that similarity exerts an indirect effect on identification by means of negative emotions (B indirect effect = . 16, SE = .09, 95 % CI [.01, .41]). That is, similarity induced a deeper experience of negative emotions (B = .35, SE = .17, p < .041) and these, in turn, were associated with a greater identification with the protagonist of the public service announcement regarding gender violence (B = .46, SE = .11, p < .001). Therefore, H1 was partially supported empirically.

Hypothesis 2: Effect of similarity on the risk perception of becoming a victim of abuse

H2 was tested through multiple linear regression analysis in which the independent variable was the experimental condition (0 = low similarity, 1 = high similarity to the protagonist), the negative emotions index was introduced in the analysis as a covariate, and the risk perception index for gender violence was the dependent variable. It was observed that similarity had no statistically significant effect on risk perception (β = -.18, p = .129). Moreover, negative emotions did not affect the dependent variable (β = .02, p = .816). Thus, H2 was not confirmed by the data.

Hypothesis 3: Effect of modern racism as a moderator variable of the relation between similarity and identification

To test H3, we used the PROCESS macro (model 1), which allowed us to analyze whether there was an interaction effect between similarity and modern racism on the identification with the protagonist. It was observed that the interaction effect was not statistically significant (B = .25, SE = .22, p = .259), that is, that the impact of similarity on identification was not moderated by modern racism. Therefore, H3 is not supported empirically. Modern racism did affect identification (B = -.33, SE = .15, p < .039), that is, the higher the level of modern racism, the less the identification, regardless of the version viewed by the participants.

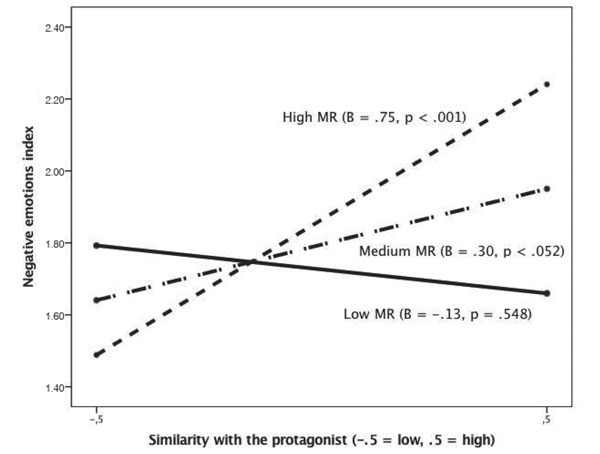

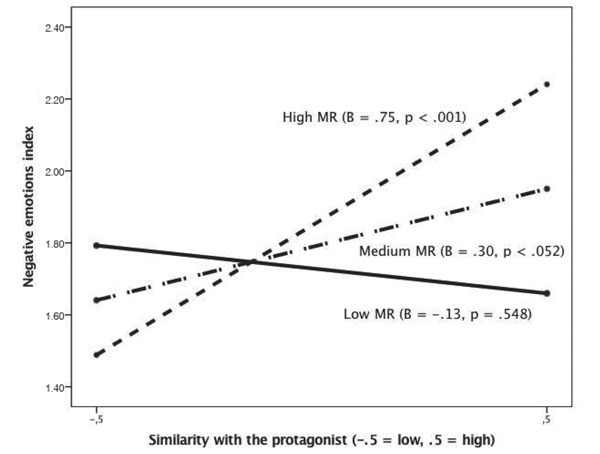

Since differences in the negative emotions were observed, we tested whether that effect could be moderated by modern racism. To do so, we again employed the PROCESS macro (model 1), observing that the interaction effect was statistically significant (B = .52, SE = .18, p < .006), that is, the impact of similarity on negative emotions was moderated by modern racism. Analysis ofthe conditional effect of similarity on negative emotions showed that that effect was not statistically significant among the participants with a low score in modern racism (B = -.13, SE = .22, p = .548), was marginally significant when the participants showed a moderate level of modern racism (B = .30, SE = .15, p = .052), and it was statistically significant in cases where modern racism was high (B = .75, SE = .22, p < .001). These results show that similarity induced more negative emotions, but only when the modern racism levels were moderate to high (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Moderating effect of modern racism (MR) on the relation between similarity with the protagonist and experiencing negative emotions

Source: Own elaboration.

Hypothesis 4: Indirect effect of similarity on risk perception

Hypothesis 4 postulated a moderated mediation model in an attempt to understand the roles played by identification with the protagonist in the public service announcement as a mediating variable of the effect of similarity on risk perception, but also taking into account the role of modern racism as a moderating variable. To test this hypothesis, we used the PROCESS macro (model 7) for SPSS developed by Hayes (2013). This macro makes it possible to test different mediational models based on the bootstrapping technique. Model 7 of this procedure allowed us to calculate the conditional indirect effects, that is, to analyze the effect of an independent variable (similarity to the protagonist of the video) on a dependent variable (risk perception), through a mediating variable (identification with the protagonist) and for different levels of a moderating variable (modern racism). In our study, the conditional indirect effects were calculated using 10,000 bootstrapping samples, generating confidence intervals of the bias-corrected bootstrap type.

The results showed that, as had been previously observed, similarity did not significantly affect identification (B = -.46, SE = .54, p = .388). The moderating effect of modern racism on the relation between similarity and identification was not statistically significant either (B = .25, SE = .22, p = .259), although modern racism did affect identification (B = -.33, SE = .15, p < .039). Identification with the protagonist was associated with higher risk perception (B = .83, SE = .29, p < .006), but no conditional indirect effect turned out to be statistically significant, and therefore the moderated mediation index was not statistically significant either (IMM = .21, SE = .22, 95 % CI [-.14, .76]). From these results, it can be deduced that identification with the protagonist does play a relevant role in the activation of risk perception. In any case, since similarity did not affect identification and modern racism did not exert a moderating effect, H4 was not confirmed by the data.

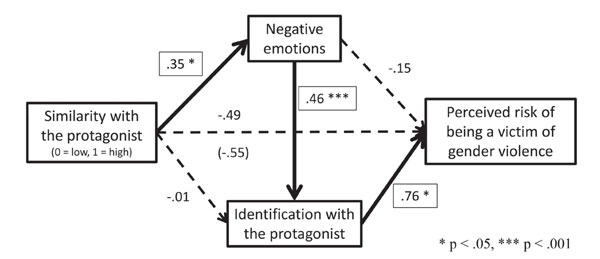

Taking into account that modern racism moderated the effect of similarity on the negative emotions experienced, affected identification, and that identification significantly influenced risk perception, we tested a new mediational model. A mediation model with two mediators was postulated (negative emotions and identification) that operate in sequence to determine the indirect effect of similarity on risk perception, and modern racism was included as a covariable. The PROCESS macro was again used to test this model, but, on this occasion, model 6 (Hayes, 2013) was used. The analysis performed (see Figure 2) revealed that similarity was positively associated in a statistically significant way with experiencing negative emotions (B = .35, SE = .17, p < .041). In turn, the negative emotions were statistically associated with identification with the protagonist (B = .46, SE = .11, p < .001). Finally, identification significantly influenced risk perception (B = .76, SE = .36, p < .039). In addition, the indirect effect of similarity on risk perception after including the two mediating variables considered to operate in sequence (negative emotions -> identification) turned out to be statistically significant (B indirect effect = . 12, SE = .10, 95 % CI [.001, .45]).

Figure 2. Results of the mediation model: The indirect effect of similarity on risk perception through negative emotions and identification with the protagonist (showing the unstandardized regression coefficients, B)

Source: Own elaboration.

Conclusions and Discussion

The results of our experimental study shed light on the importance of similarity with the protagonist of entertainment-education narratives applied, in this case, to campaigns aimed at raising awareness of gender violence. This study also makes a significant contribution to research into narrative persuasion and the role of emotions and identification with characters as explanatory mechanisms (de Graaf, 2014; de Graaf et al., 2012; Hoeken & Fikkers, 2014; Hoeken et al., 2016; Hoeken & Sinkeldam, 2014; Igartua & Barrios, 2012; Igartua & Vega, 2016).

Although the hypotheses formulated were not completely corroborated by the analysis, important results were obtained towards progress in this research field. The first hypothesis posited a direct effect of similarity on identification; however, what we found was that similarity exerts an indirect effect on identification by means of negative emotions. This result is important because it indicates that only narratives that have characters similar to the audience to which they are addressed will have the potential to provoke identification with the protagonist, through an emotional route.

The third hypothesis posited that the effect of similarity on identification would be conditioned by the previous level of prejudice the participants felt towards immigrants. In this context, modern racism has been pointed out in previous studies as a relevant variable for understanding intergroup relations (McConahay et al., 1981) and the process of reception and impact of fictional feature-length movies in which significant examples of relations between characters pertaining to ethnic or cultural minorities and characters of the ingroup are shown (Eno & Ewoldsen, 2010; Igartua & Frutos, 2017). The results show that modern racism (taken as a measure of prejudice towards immigrants) did not condition identification. However, two significant results were indeed obtained in this context: first, that the individuals with a higher level of modern racism identified less with the protagonist of the narrative (regardless of her nationality); and second, that modern racism moderated the relation between similarity and negative emotions.

The results allow us to confirm that similarity exerts a differential effect on experiencing negative emotions when watching a dramatic narrative about a woman who is a victim of gender violence, as a function of modern racism. The participants with a low level of modern racism reacted in a similar way as far as negative emotions were concerned when faced with a story whose protagonist was either an immigrant woman or a Spanish native. However, the participants who showed a high level of prejudice towards immigrants experienced more intense negative emotions when they were told that the protagonist victim of gender violence was Spanish than when she was said to be a foreign immigrant to Spain. In other words, for individuals with a high level of prejudice towards immigrants, the "drama" of the Spanish Maria caused more unease than the same drama experienced by the immigrant Maria.

Thus, it has been possible to confirm that individuals' previous level of prejudice towards immigrants conditions their reception processes (experiencing negative emotions and identification). Although modern racism did not moderate the relation between similarity and identification, it did reduce the level of identification regardless of the demographic characteristics of the protagonist of the narrative. Moreover, modern racism moderated the relation between similarity and negative emotions. These results can be interpreted by taking the following elements into account: a) gender violence is presented in the news as a problem affecting mostly immigrants, b) gender violence is perceived as affecting underdeveloped countries to a greater extent, and, c) immigrant women are thought to be more vulnerable to gender abuse (Bosch-Fiol & Ferrer-Pérez, 2012; Meil, 2014; Román et al., 2011).

The second hypothesis postulated an effect of similarity on the risk perception of becoming a victim of gender violence. In turn, the fourth hypothesis posited an explanation of that relation taking into account the role of identification (as a mediating variable) and modern racism (as a moderating variable). Although the moderated mediation model postulated did not turn out to be significant, it was observed that similarity did exert an indirect effect on risk perception through negative emotions and identification. Regardless of the participants' level of modern racism, a narrative with a main character similar in demographic terms caused more negative emotions to be felt, which led to greater identification with the character and, in turn, was associated with a greater risk perception of becoming a victim of abuse. It can thus be affirmed that similarity in demographic terms (nationality, in this case) is a relevant process in increasing identification with the protagonist of the story through inducing emotions, and that this conditions the persuasive impact. On a theoretical level, these results endorse the centrality of similarity, (negative) emotions and identification in explaining narrative persuasion processes and converge with the results of previous studies (de Graaf, 2014; Hoeken et al., 2016). The present study provides evidence on the relationship between similarity with the character and identification, a subject of open debate in current research on narrative persuasion, since previous research has yielded contradictory results (see, de Graaf et al., 2016; Tukachinsky, 2014).

The result of the mediational analysis is consistent with those obtained in the study by Hoeken and Sinkeldam (2014), even though these authors postulated an inverse sequence (and in their study, they did not manipulate similarity but rather the attractiveness of the character). In the present study, it is evident that a highly intense dramatic narrative (showing examples of incidents of physical abuse) immediately provokes negative emotions, which can lead spectators to identify with and put themselves in the place of the victim. Given the dramatic nature of the scenes shown in the video, it is logical that identification is not a requirement for producing emotional impact; rather, the latter takes place as an automatic process. Once the spectators have put themselves in the protagonist's shoes, it is logical to expect their risk or vulnerability perception to increase. In this regard, a previous study showed that identification with the main characters of a TV series that broached the consequences of an undesired teenage pregnancy increased the audience's risk perception and this in turn stimulated a higher behavioral intention to prevent pregnancy (Moyer-Gusé & Nabi, 2010). Thus, the findings of our study are consistent with the idea that people are susceptible to attitudes shown by characters in narratives (de Graaf et al., 2012). It can be confirmed that the process is posited as follows: If the protagonist of a narrative is perceived as similar, a cognitive-emotional connection with that character takes place more easily; this will cause the opinions, beliefs and attitudes of the character to have a greater impact on the audience, because when people identify with a character, they are more likely to take on the character's point ofview than when that connection does not exist.

One limitation of this study has to do with the manipulation of the nationality of the protagonist. It was observed that recall of the nationality was not the same in the two conditions, such that a significant percentage of the individuals who saw the video in which the protagonist was said to be Argentinian either thought she was Spanish (11.4 %) or could not recall the information (11.4 %). Despite the fact that the large majority of participants correctly identified the nationality of the protagonist in both experimental conditions (more than 60 %, when the information was only presented at the beginning of the video and only lasted 8 seconds), it is very likely that the manipulation of the similarity would have yielded stronger effects in regard to identification if the protagonist had been described as Moroccan, given that, as of today, Moroccan immigrants are the immigrant group that arouses most dislike in Spanish public opinion (Cea DAncona & Valles Martínez, 2014). In future studies, narratives with protagonists who are immigrants pertaining to stigmatized groups should be used (Chung & Slater, 2013). Other factors involved in the construction of characters that could increase their similarity should also be looked into.

With respect to the practical implications of the results of our study, and in relation to the development of campaigns for raising awareness of gender violence, it would be advisable to work with narratives in which the nationality of the protagonist is not indicated (or shown indirectly), as this can condition the effectiveness of the message (see, Igartua, 2013, where experimental evidence is provided on the attitudinal impact of crime news that alludes to the nationality of offenders). Campaigns designed to raise awareness of gender violence that feature protagonists who are immigrants (as a stigmatized out-group) could reinforce stereotypes about the link between immigration and gender violence, and thus have a pernicious effect, instead of contributing to the eradication of gender violence. Recall that the positive indirect effect of similarity on risk perception means that, when similarity is low, a lower risk perception is stimulated.

Notes

3 "In convenience sampling, the sample consists of people most readily accessible or willing to be part in the study (...). Convenience samples using undergraduate students are especially common in the social sciences" (Crano, Brewer, & Lac, 2015, p. 234). In fact, Hayes (2005) has pointed out that "true probability sampling is rarely ever done in communication research" (p. 41). While the probability sampling methods are the best approach to make population inferences, nonprobability sampling (like using convenience samples) is a valid approach to make process inferences (see, Hayes, 2005, pp. 41-44, for a definition of the concept of process inference).

References

Bosch-Fiol, E., & Ferrer-Pérez, V. A. (2012). Nuevo mapa de los mitos sobre la violencia de género en el siglo XXI [New map ofthe myths about gender violence in XXI century]. Psicothema, 24(4), 548-554.

Braddock, K., & Dillard, J. P. (2016). Meta-analytic evidence for the persuasive effect of narratives on beliefs, attitudes, intentions, and behaviors. Communication Monographs, 83(4), 446-467. doi: 10.1080/03637751.2015.1128555

Cea D'Ancona, M. A., & Valles Martínez, M. (2014). Evolución del racismo, la xenofobia y otras formas conexas de intolerancia en España [Evolution of racism, xenophobia and related intolerance in Spain]. Madrid: OBERAXE, Ministerio de Empleo y Seguridad Social.

Chen, M., Bell, R. A., & Taylor, L. D. (2016). Narrator point of view and persuasion in health narratives: The role ofprotagonist-reader similarity, identification, and self-Referencing. Journal of Health Communication, 21(8), 908-918. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2016.1177147

Chung, A. H., & Slater, M. D. (2013). Reducing stigma and out-group distinctions through perspective-taking in narratives. Journal of Communication, 35(3), 442-463. doi: 10.1111/jcom.12050

Cohen, J. (2001). Defining identification: A theoretical look at the identification of audiences with media characters. Mass Communication & Society, 4(3), 245-264. doi: 10.1207/S15327825MCS0403_01

Crano, W. D., Brewer, M. B., & Lac, A. (2015). Principles and methods of social research. New York, NY: Routledge (3er edition).

de Graaf, A. (2014). The effectiveness of adaptation of the protagonist in narrative impact: Similarity influences health beliefs through self-referencing. Human Communication Research, 40(1), 73-90. doi: 10.1111/hcre.12015

de Graaf, A., Hoeken, H., Sanders, J., & Beentjes, J. W. J. (2012). Identification as a mechanism of narrative persuasion. Communication Research, 39(6), 802-823. doi: 10.1177/0093650211408594

de Graaf, A., Sanders, J., & Hoeken, H. (2016). Characteristics of narrative interventions and health effects: A review of the content, form, and context of narratives in health-related narrative persuasion research. Review of Communication Research, 4, 88-131. doi: 10.12840

Eno, C. A., & Ewoldsen, D. R. (2010). The influence of explicitly and implicitly measured prejudice on interpretations of and reactions to black film. Media Psychology, 13(1), 1-30. doi:10.1080/15213260903562909

Erez, E., Adelman, M., & Gregory, C. (2009). Intersections of immigration and domestic violence: Voices ofbattered immigrant women. Feminist Criminology, 4(1), 32-56. doi: 10.1177/1557085108325413

Gaertner, S. L., & Dovidio, J. F. (1986). The aversive form of racism. In J. F. Dovidio & S. L. Gaertner (Eds.), Prejudice, discrimination, and racism (pp. 61-89). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Green, M. C., & Brock, T. C. (2000). The role of transportation in the persuasiveness of public narratives. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(5), 701-721. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.5.701

Hayes, A. F. (2005). Statistical methods for communication science. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrecne Erlbaum Associates.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. A regression-based approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Hoeken, H., & Fikkers, K. M. (2014). Issue-relevant thinking and identification as mechanisms of narrative persuasion. Poetics, 44, 84-99. doi: 10.1016/j.poetic.2014.05.001

Hoeken, H., Kolthoff, M., & Sanders, J. (2016). Story perspective and character similarity as drivers of identification and narrative persuasion. Human Communication Research, 42(2), 292-311. doi: 10.1111/hcre.12076

Hoeken, H., & Sinkeldam, J. (2014). The role of identification and perception of just outcome in evoking emotions in narrative persuasion. Journal of Communication, 64(5), 935-955. doi: 10.1111/jcom.12114

Igartua, J. J. (2013). Attitudinal impact and cognitive channelling of immigration stereotypes through the news. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 68, 599-621.

Igartua, J. J., & Barrios, I. (2012). Changing real-world beliefs with controversial movies: Processes and mechanisms of narrative persuasion. Journal of Communication, 62(3), 514-531. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2012.01640.x

Igartua, J. J., & Frutos, F. J. (2017). Enhancing attitudes toward stigmatized groups with movies: Mediating and moderating processes of narrative persuasion. International Journal of Communication, 11, 158-177.

Igartua, J. J., & Vega, J. (2016). Identification with characters, elaboration, and counterarguing in entertainment-education interventions through audiovisual fiction. Journal of Health Communication, 21(3), 293-300. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2015.1064494

McConahay, J. B., Hardee, B. B., & Batts, V. (1981). Has racism declined in America? It depends on who is asking and what is asked. The Journal of Conflict Resolution, 25(4), 563-579.

Meil, G. (2014). Percep ción social de la violencia de género [Social perception of gender violence]. Madrid: Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad.

Moyer-Gusé, E. (2008). Toward a theory of entertainment persuasion: Explaining the persuasive effects of entertainment-education messages. Communication Theory, 18(3), 407-425. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2885.2008.00328.x

Moyer-Gusé, E., Chung, A. H., & Jain, P. (2011). Identification with characters and discussion of taboo topics after exposure to an entertainment narrative about sexual health. Journal of Communication, 61 (3), 387-406. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2011.01551.x

Moyer-Gusé, E., & Nabi, R. L. (2010). Explaining the effects of narrative in an entertainment television program: Overcoming resistance to persuasion. Human Communication Research, 36(1), 26-52. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2958.2009.01367.x

Park, S.-Y. (2012). Mediated intergroup contact: Concept explication, synthesis, and application. Mass Communication and Society, 15(1), 136-159. doi: 10.1080/15205436.2011.558804

Robinson, M. J., & Knobloch-Westerwick, S. (2017). Bedtime stories that work: The effect of protagonist liking on narrative persuasion. Health Communication, 32(3), 339-346. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2016.1138381

Román, M., García, A., & Álvarez, S. (2011). Tratamiento informativo de la mujer inmigrante en la prensa española [Information processing of immigrant women in Spanish newspapers]. Cuadernos de Información, 29, 173-186.

Tukachinsky, R. (2014). Experimental manipulation of psychological involvement with media. Communication Methods and Measures, 8(1), 1-33. doi: 10.1080/19312458.2013.873777

Wright, E. M., & Benson, M. L. (2010). Immigration and intimate partner violence: Exploring the immigrant paradox. Social Problems, 57(3), 480-503. doi: 10.1525/sp.2010.57.3.480