10.5294/pacla.2016.19.4.6

Article

The Contextualization of the Watchdog and Civic Journalistic Roles:

Reevaluating Journalistic Role Performance in U.S. Newspapers

Contextualización de los roles periodísticos cívicos y del perro guardián:

reevaluación del desempeño del rol periodístico en los periódicos estadounidenses

Contextualização dos papéis jornalísticos cívicos e do cão guardião:

reavaliação do desempenho do papel jornalístico nos jornais estadunidenses

Lea Hellmueller1

Claudia Mellado2

Lindsey Blumell3

Jennifer Huemmer4

1 Texas Tech University. Estados Unidos. lea.hellmueller@ttu.edu

2 Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaiso. Chile. claudia.mellado@pucv.cl

3 Texas Tech University. Estados Unidos. lindsey.blumell@ttu.edu

4 Texas Tech University. Estados Unidos. jennifer.huemmer@ttu.edu

Recibido: 2016-08-26 / Enviado a pares: 2016-09-01 / Aprobado por pares: 2016-09-22 / Aceptado: 2016-10-03

Para citar este artículo / to reference this article / para citar este artigo

Hellmueller, L., Mellado, C., Blumell, L. & Huemmer, J. (2016). The contextualization of the watchdog and civic journalistic roles: Reevaluating journalistic role performance in U.S. newspapers. Palabra Clave, 19(4), 1072-1100. DOI: 10.5294/pacla.2016.19.4.6

|

Abstract This study examines the two dominant U.S. journalism models —the watchdog and civic-oriented professional performance— in the aftermath of the economic crises. The study, based on a content analysis of 1,421 news stories published by five national U.S. dailies, measures journalists' role conception through a content analysis of newspaper articles, examining the concept of journalistic role performance. The findings indicate different contextualizations of the two roles: The civic journalism performance was mostly found in stories dealing with issues such as human rights, demonstrations, and religion. The watchdog model was found in stories dealing with religion as well, but was found more frequently than the civic model in stories covering the government, police and crime. While the overall results indicate shifting roles of journalists toward a more civic approach, the traditional watchdog role remains important in covering politics. The roles journalists perform and their implications for U.S. news coverage are discussed. Keywords : Professional roles; role performance; gatekeeping theory; watchdog; civicoriented journalism; content analysis (Source: Unesco Thesaurus). |

Resumen Este estudio examina los dos modelos periodísticos dominantes en Estados Unidos, el perro guardián y el desempeño profesional orientado a la ciudadana, después de las crisis económicas. El estudio, basado en un análisis de contenido de 1,421 noticias publicadas por cinco diarios nacionales de Estados Unidos, mide la concepción del papel de los periodistas a través de un análisis de contenido de artículos periodísticos, examinando el concepto de desempeño de rol periodístico. Los resultados indican una contextualización diferente para cada uno de los dos roles: el desempeño del periodismo cívico se encontró principalmente en historias que trataban temas como derechos humanos, demostraciones y religión. El modelo del perro guardián también se encontró en historias que trataban la religión, pero era más frecuente que el modelo cívico en historias que cubrían el Gobierno, la Policía y el crimen. Si bien los resultados generales indican el cambio de roles de los periodistas hacia un enfoque más cívico, el rol tradicional del perro guardián sigue siendo importante en la cobertura política. Se analizan las funciones que desempeñan los periodistas y sus implicaciones para la cobertura de noticias en Estados Unidos. Palabras clave : Roles profesionales; desempeño de roles; teoría del guardabarreras; perro guardián; periodismo cívico; análisis de contenidos (Fuente: Tesauro de la Unesco). |

Resumo Este estudo examina os dois modelos jornalísticos dominantes nos Estados Unidos, o cão guardião e o desempenho profissional orientado à cidadania, depois das crises econômicas. O estudo, baseado em uma análise de conteúdo de 1,421 notícias publicadas por cinco diários nacionais dos Estados Unidos, avalia a concepção do papel dos jornalistas através de uma análise de conteúdo de artigos jornalísticos, examinando o conceito de desempenho do papel jornalístico. Os resultados indicam uma contextua-lização diferente para cada um dos dois papeis: o desempenho do jornalismo cívico foi encontrado principalmente em histórias que tratavam temas como direitos humanos, demonstrações e religião. O modelo do cão guardião também foi encontrado em histórias que tratavam a religião, mas era mais frequente do que o modelo cívico em histórias que cobriam o governo, a polícia e o crime. Embora os resultados gerais indiquem a mudança de papeis dos jornalistas rumo a um enfoque mais cívico, o papel tradicional do cão guardião continua sendo importante na cobertura de política. Analisam-se as funções desempenhadas pelos jornalistas e suas implicações para a cobertura de notícias nos Estados Unidos. Palavras-chave : Papeis profissionais; desempenho de papeis; teoria do gatekeeper; cão guardião; jornalismo cívico; análise de conteúdos (Fonte: Tesauro da Unesco). |

The landscape of American journalism is in a potential state of flux, no longer only dominated by the unilateral presence of the watchdog model, but expanding to include an interventionist approach (Hanitzsch, 2007). One of the most recent impetuses to restructure the field of journalism occurred after the watchdog model was deemed antiquated and flawed in the aftermath of 9/11 (Bennett, Lawrence, & Livingston, 2008). As the fog of tragedy cleared, journalists began questioning their roles and responsibilities to the public. Many American journalists reinterpreted their role conceptions to reflect the burgeoning desire to guide, help, and intercede for the American public (Bennett et al., 2008) and within the last fifteen years, journalists started re-conceptualizing their roles to adhere to a more civic-oriented form of journalism (Voakes, 1999). Conversely, other studies have found that journalists' role conceptions maintain a strong adversarial bent and are consistent with the watchdog model of journalism (Willnat & Weaver, 2014; Plaisance & Skewes, 2003), a situation that not only exists in the U.S. but also in regions such as Latin America (Mellado, 2012; Hanitzsch et al., 2011).

Such survey research tackles the question of professionalism on a rather normative level that examines how journalists understand their roles in society. In spite of this, there is no conclusive evidence to support the assumption that journalists' survey responses that eventually contribute to their reporting, and thus to the news in a particular society (Mellado & Van Dalen, 2014; Tandoc, Hellmueller, & Vos, 2013). By shifting the interest of investigation from the question of how journalists understand their role in society to the actual practices of journalists and its news content, the results presented in this article provide a reflection of journalistic practice as it intersects with the manifestation of the watchdog and civicoriented journalistic professionalism in news content and the use of sources. The theoretical focus of this study is journalistic role performance. Studies on Journalistic Role Performance are concerned with the collective outcome of concrete newsroom decisions and the style of news reporting, influenced by internal and external forces (Mellado, 2015). The examination of professionalism in practice provides a novel examination, shifting the focus of research from journalists' understanding of their role, to the news output of journalistic roles. The aim is to understand the state of U.S. journalism by examining the journalistic ideals as they occur in actual practice (e.g., as proposed by Blumler & Cushion, 2014). With a change in technology and with the turn of the 21st century, it is less natural for journalists to turn to elite sources only. Particular attention is paid, therefore, to the challenge of excluded voices and the presence of the civic-oriented role performance.

Based on that rationale, this study maps the shift from watchdog to civic-oriented U.S. journalism by conducting a content analysis of 1,421 articles published in the The Washington Post, The New York Times, USA Today, The Los Angeles Times, and the Wall Street Journal. The roles news organizations perform are not without consequences: whether news organizations or journalists perform a watchdog or a civic-oriented role in news stories relates to the sources that are chosen, the topics that are covered, and the media agenda that is built in the 21st century.

The Shift from Journalistic Role Conceptions to Role Performance

Journalistic role conception has been defined as journalists' perceptions of journalism's social functions in society (Donsbach, 2008; Weaver et al., 2007). An impressive body of literature is available to understand role conceptions or professional worldviews, mostly with an underlying normative assumption that those roles will eventually inform the news content produced (e.g., Graber & Smith, 2005; Hanitzsch, 2011; Shoemaker & Reese, 1996).

In other words, it is assumed that journalists will select, present, and inform the public in accordance to their role, their idea of what professional journalism entails. Ideologically, the individualistic conception of a journalist's basic role consists of their responsibility to gather and disseminate factual information (Weaver, 1998; Weaver and Willnat, 2014). However, this ideological responsibility is at times disconnected from the reality of journalism practice when journalists operate in a news structure that is greatly influenced by politics, culture, financial demands, and media corporations (de Burgh, 2012 p. 8). Therefore, due to these influences, journalists often perform journalistic roles that may differ from personal role ideals. For example, Hassid's (2011) observation of Chinese news culture identified a growing number of foreign or formally educated domestic journalists that are attempting to transform journalism from "propaganda to professionalism," (p. 819) but this is limited due to the country's long established and highly censored Maoist and/or communist capitalist model.

In this empirical study, we shift our focus from journalistic role conceptions to journalistic role performances. The most recent initiative to study professional roles in news is the 28-country project, Journalistic Role Performance around the Globe, that connects characteristics of journalistic roles with reporting styles as analyzed by content analysis (Mellado, 2015; Hellmueller & Mellado, 2015; Mellado & Lagos, 2014; Mellado & Van Dalen, 2013).

One of the most commonly known journalistic models grounded in both education and professional settings is the watchdog model (Strelitz & Steenveld, 1998). Watchdog journalism is of tentimes synonymous with Western media and, in particular, with the American press since it is most commonly practiced and taught there (Hanitzsch, 2011). While journalists rarely dispute the common presence of the watchdog model, to state that the watchdog model thrives continuously is an assumption. Many social and economic factors influence the effectiveness of the watchdog model, so much so that investigative reporting does not only unearth longstanding issues, but also the failings of daily journalism (Berry, 2009).

A second model that involves embracing a public service role is the civic or public journalism model. This model is, at times, challenged as a threat to professionalism and has failed to be adopted universally in the United States (Shafer & Aregood, 2012). Nevertheless, due to recent developments that threaten journalistic autonomy such as increased corporate ownership and competition from unofficial online sources (McDevitt, Gassaway, & Pérez, 2002), embracing civic journalism may increase professional credibility by positioning journalists closer to their audiences.

The purpose of highlighting these two models is that, despite the strong watchdog tradition in the United States, there is a continual waning trust of the American public in its news sources and an increased perception that the news is overtly biased (Gil de Zuniga & Hinsley, 2013). Therefore we were interested to see if the civic model is, despite criticisms, emerging as an alternative to the watchdog performance in U.S. journalism.

Watchdog Journalism

Literature dedicated to watchdog journalism does not always provide a definitive concept to what the watchdog model should entail (Pinto, 2009; Berry, 2009). In the 1960s with the advent of the Vietnam War, civil rights movement, and political corruption scandals, the concept of watchdog journalism evolved to include in-depth or investigative reporting (Feldstein, 2006, p. 234). It was at that time that newsrooms throughout the country began to set up investigative teams and in-depth news programs premiered on television (Glasser & Ettema, 1989). Woodward and Bernstein's unearthing of what is now known as the Watergate scandal was, perhaps, the most prominent example of in-depth investigative news reporting (Carlson, 2010). Although coverage of the Watergate scandal is considered one of the greatest examples of investigative journalism in American history (De Witt, 1992), it can be argued that this coverage was the exception rather than the norm. Public cynicism about watchdog journalism does not prevent journalists from aspiring to the watchdog model, or at least accepting that it is a highly emphasized performative model in the United States. In a recent study of journalists, results found that 78% of journalists still perceive their role as a government watchdog to be fundamental to their reporting (Willnat & Weaver, 2014). This is the highest agreement since Willnat and Weaver (2014) began surveying journalists in 1971.

Marder (1998) explains that the watchdog model cannot consist of occasional in-depth exposés, but that it requires journalists to ask elites/government leaders hard-hitting questions that the general public cannot. In a world where information management has become a sophisticated branch in which every notable business/organization invests large amounts of money, watchdog journalism is particularly important in scraping below this ever polished surface (Schultz, 1998). Yet, this principled model of journalists acting as watchdogs becomes complex when factors such as prestige and structural bias are taken into account. For example, journalists treat different politicians differently and different journalists are treated differently by politicians according to their reputation and status (Gnisci, Van Dalen, & Di Conza, 2014).

Much scholarship in recent years (Powell, 2011; Lewis & Reese, 2009; Kumar, 2010; Ho, Binder, Becker, Moy, Scheufele, Brossard, & Gunther, 2011; Bennett, 2009) has revolved around the sleeping watchdog that failed to be critical post September 11th resulting in the Iraq invasion in 2003. Evans (2010) explains that after the end of the Cold War, political analysts and perhaps journalists themselves were looking for a new scapegoat for the causes of international conflicts. It can be argued that the "axis of evil" and "war on terror" was an attempt to fill this void and therefore contributed to how post 9/11 events were covered. These catchphrases by the Bush administration were adopted with little resistance into news coverage across several media platforms around the U.S. (Harmon & Muenchen, 2009). Glazier and Boydstun (2012) conclude that the press failed in their post 9/11 and Iraq war coverage as watchdogs by refusing to question authority and fact check. Starkman (2011) points out that the watchdog was again bark-less during the 2008 financial crisis when journalists failed to investigate Wall Street Bankers and mortgage lenders.

Criticisms towards journalists' failing to bark are rooted in the cohesiveness rather than the skepticism between American journalists and the American presidential administration (Entman, 2004; Bennett, 2009). Furthermore, American journalists still perceive themselves to be watchdogs (Willnat & Weaver, 2014). Therefore, it is necessary to understand if the newspaper content matches this perception.

Civic Oriented Journalism

Civic journalism is a relatively novel model of journalism that, according to Voakes (1999), can be traced to experiments conducted in the 1980's and 1990's by the Wichita Eagle. Not only is civic oriented journalism a new and rather untraditional model, but the objectives of civic oriented journalism vary greatly from other popular journalism models. Massey and Haas (2002) explain the two goals of civic oriented journalism including: (1) mending the damage traditional journalism caused to community involvement and public interest and (2) making a positive impact among news audiences. Civic oriented journalism moves beyond the watchdog's goal of delivering truthful and objective content to news readers. It focuses instead on informing the public in order to activate public participation and community involvement. However, the civic oriented model of journalism is flawed in that it has no clear definition or standard. Kurpius (2002) labels civic oriented journalism as a "public discourse" and, as such, it cannot be universally defined. In other words, the conceptualization of civic journalism is dynamic; continuously evolving as the public dialogue changes and adjusts to social circumstances.

Role conception was a crucial factor in the development of the civic oriented model of journalism. According to Rosen (1999), journalists became dissatisfied with the limitations of their roles and desired a deeper sense of purpose in their work. The desire for meaningful, discursive journalism developed into what is now often referred to as civic (or public) journalism (Rosen, 1999). Shoemaker and Vos (2009) explain, "the emergence of public journalism reflects a shift of journalists' roles with more emphasis on community involvement and local news" (p.47). As journalists' role conceptions shift, gatekeeping practices may change to include stories, language, and other style choices that reflect the civic oriented model. As such, the tactics and strategies used to accomplish the aforementioned objectives of civic journalism are unique to the civic oriented model. For example, "Civic journalism has promoted additional styles of reporting that contribute to public deliberations on important issues and how we might address these issues" (Hodgetts Chamberlain, Scammell, Karapu, & Nikora, 2008, p. 46). To facilitate a public discourse on important issues, civic journalists often use reporting styles that combine both narrative storytelling with investigative reporting (Lambeth, Meyer, & Thorson 1998). This demonstrates the extent to which role conception becomes integrated into the very fabric of reporting styles and other gatekeeping decisions. Although civic oriented journalism developed popularity after 9/11 (Bennett et al., 2008), Ahva (2012) argues that American journalistic values are less conducive to the civic oriented model of journalism than journalistic values in other parts of the world. Thus this study aims to reexamine the level of importance attributed to individual journalistic role conception by focusing instead on how the civic oriented model manifests through the routine level of the gatekeeping process as demonstrated by the content produced rather than the ideological values of the journalists.

Source Selection and Journalistic Role Performance

News stories that emphasize citizen sources and community perspectives are often consistent with the civic oriented model of journalism (Kurpius, 2002). The objectives of civic journalism fundamentally influence the way civic journalists select sources (Lee, 2001). Journalists, adhering to the civic oriented model, utilize community leaders with the potential to influence change as key sources in an attempt to connect with the community (Kurpius, 2002). Providing citizen sources in news story coverage can often have significant effects on the public. Most notably, Kurpius' (2002) research claims that using citizen sources provides a platform for underrepresented populations to express beliefs and opinions.

Civic oriented journalism, in summary, aims to instill citizens with a sense of autonomy by providing the audience with information and the potential for public dialogue. Civic journalists use gatekeeping techniques to shape news stories with the ultimate goal of prompting the public to participate in both dialogue and community action (Hodgetts et al., 2008). Civic role performance has been defined with nine indicators to measure the level or presence of civic journalism in news content (Mellado, 2015). The first indicators are citizen perspective, citizen demand and citizen questions and have to do with listening to citizens' stories, basically giving a voice to ordinary people. Another indicator is paying systematic attention to the credibility of the public's messages and giving support to citizen movements when a news story explicitly supports an organization as a positive example to follow. Other indicators of civic journalism are stimulating citizen deliberation, and building an understanding of issues (Voakes, 2004). Meanwhile, highlighting the impact of political decisions on local communities is another important indicator of the civic-oriented journalism model.

Gatekeeping Forces and Journalistic Role Performance

The individual and routine levels of gatekeeping contribute to the theoretical framework associated with the performance of journalistic roles. The level of individual communication, specifically, involves individual processes of analysis and interpretation (Shoemaker & Vos, 2009). While previous studies have examined the individual level of gatekeeping through the manifestations of journalistic role conceptions (Shoemaker & Reese, 1996), research regarding journalistic role conception has relied heavily on self-report resulting in an under-explored gap between what journalists say they do and what they actually produce in print. Individual role conceptions and ideologies may, for example, be mitigated by the governing control of the social institutional gatekeepers including markets, advertisers, governments, and sources (Shoemaker & Vos, 2009). Similarly, the routine level of the gatekeeping process may negate the influence of a journalist's personal role conception resulting in an overall performance that does not reflect the journalist's personal understanding of his or her role (Mellado & Lagos, 2014). Variables used in the routine gatekeeping level of structuring a newspaper must be examined to better understand the significance of a news story.

Routine Level: Structuring Newspapers

The U.S.' top circulated newspapers were selected for this study because national American newspapers do influence the quality of journalism in the country as a whole (Ferguson, 2000). Quality of journalism, and in this the case quality of elite newspapers, is also affected by how content is structured and emphasized or not emphasized. Elements of story structure can be related to the routine levels of gatekeeping in that they are a part of the procedures (Shoemaker, Eichholz, Kim, & Wrigley 2001) that journalists and editors make daily that affect which information passes through the gate and which does not. The longer the coverage, the more prominently a story is placed and which sources are used can add or subtract from the message of the news article. Also, it can assist researchers in understanding what emphasis certain models are given over others, ultimately determining the performance role of a journalist. For the purposes of this study, the story structure elements that will be examined are story type, prominence and sources as routine forces to predict role performance.

Story Type

The basic story types found in Western newspapers are article (basic news story) and feature. Articles are the most commonly used story type in newspapers, which are meant to be read quickly and therefore follow a specific "inverted pyramid" structure (Ogle, Klemp, & McBride, 2007). As the name implies, journalists use the "inverted pyramid" to place the most important information at the top of the article, such as the who, what, where, when and why of a story (Pottker, 2003). This style of writing is taught through aspiring journalists' formal training (usually in post-secondary education), a measure of the routine level (Cassidy, 2006) Features are not only longer in length than articles, yet they give the journalist more room to be creative, yet still logical (Stephenson, 1998). Due to the length of a feature, it does not have the same competition on the page from other articles, and therefore a more conversational, narrative approach is often used (Stephenson, 1998). Although features are longer in length and sometimes prominence, they are often located in the inside pages of a newspaper, whereas breaking news and hard news will often be featured as articles (Pottker, 2003). Deciding whether or not a story will be written as a feature or an article is usually the decision of the supervisor or editor and also a measurement of the routine level (Cassidy, 2006).

Story Placement

The placement of a story in the newspaper is another important variable in the routine level of the gatekeeping process. Editorial discretion is used daily to decide which story is the most important of the day and will therefore appear on the front page (Cotter, 2010). Beyond the front page, where a story is placed inside the newspaper along with the size of headline, story length, and whether or not a photo is included all play a factor in a story's prominence (Cotter, 2010). Bissell (2000) found that the routines of a newsroom govern how content is published and the emphasis of certain topics over others (the more the emphasis on a specific topic, the more likely it will appear prominently in a newspaper). While story placement cannot define journalistic role performance alone, it can help scholars better understand story topic prominence (Collins & Cooper, 2015) and, subsequently the value an organization places on specific journalistic models.

Source Type

Along with story type and placement, the sources featured in news stories fall under routine forces (Cassidy, 2006). Furthermore, evaluating the newsworthiness of sources is also decided at the routine level (Kim, 2012) and diversity of content is limited by routines (Shoemaker, 2012). Perhaps, the most prominent feature of distinguishing between the watchdog and civic-orientated model are the sources that are used. That is, the watchdog model, since its aims are to question the elites of society, will feature more government leaders, politicians, CEOs of large corporations, and other prominent members of society (Berkowitz, 2009). The civic oriented model, on the other hand, is meant to represent the people and will feature more activists, "regular" folks, and others seeking to be a voice for the people (Kurpius, 2002).

Hypotheses and Research Question

Since the majority of journalists still place a strong emphasis on the role of being a government watchdog (Willnat & Weaver, 2014), the first research question will seek to understand how much each model can be found in the news coverage:

RQ1: To what extent do the watchdog and civic oriented models manifest in news content?

Following gatekeeping theory (Shoemaker & Vos, 2009) assumptions, the roles journalists perform vary based on routine and organizational factors. The following hypotheses were posed to incorporate the assumption that journalistic roles are embedded in media organizations' routines and manifest in the stories newspapers produce.

H1: Higher prominence of the news story in the newspaper will predict higher expression of either the watchdog or the civic oriented journalism model.

Based on the literature review, it was assumed that story types such as article, reportage, or a feature would lead to different journalistic models. Thus, an additional hypothesis was posed:

H2: Story types will produce significant differences between the two journalistic performances; watchdog and the civic model.

Sourcing is one major aspect of the routine level (Shoemaker & Vos, 2009), and journalists are daily confronted with the choice of sources. Journalists are more likely to use ordinary people as sources when operating under the civic oriented model. On the other hand, sources in powerful positions such as politicians and business elites will significantly produce higher expressions of the performance of the watchdog model. Thus, a final hypothesis is posed:

H3: Source use will determine the expression of the journalistic performance, whether journalists cite expert source, ordinary people, politicians or document sources

Method

Content Analysis. This study tested the posited hypotheses by measuring role performance using content analysis data and analyzed role performance models as well as sources included in the articles. In total, the codebook consists of over 40 variables. Five printed media outlets with national circulation were content analyzed between 2012 and 2013: The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Los Angeles Times, the USA Today, and the Wall Street Journal were chosen based on ownership and geographical diversity. Newspapers were sampled that differ on those categories to get an overall idea of journalistic role performance in U.S. newspapers.

Sampling Plan. The constructed week method was applied and a stratified sample was selected for each of the newspapers (Riffe, Lacy, & Fico, 2005). For each newspaper, a Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, Saturday, and Sunday edition were selected for each half of the year, making sure that every month of the year is represented by at least one day. If we were not able to find a Sunday edition of one particular newspaper, we sampled the following day. In total, two constructed news weeks were sampled per newspaper per year. This sampling strategy is considered statistically sufficient to allow for "reliable estimates" (Riffe, Aust, & Lacy, 1993, p. 139).

The unit of analysis for this study was the news item. All news stories published in the national desk (politics, economy and so on) were sampled. Five coders were trained, but the first coding yielded insufficient reliability. The second round of coding and another on-the-spot training for discussing yielded an agreement on all the categories, analyzing step-by-step some specific newspapers together and revealing similarities and differences among the five coders. To test for intercoder-reliability three different tests were run: Cohen's Kappa, average pairwise percent agreement and Krippendorff's alpha. Agreements were reached for the source categories, Krippendorff's alpha ranged from .67 (for civic society sources) to .87 for ordinary people as sources. An agreement was reached for balance as reporting method with Krippendorff's alpha of .79. For the civic model, average pairwise percent agreement ranged from 72% (i.e., citizen perspective) to 96% (support of citizen movements). Finally, the watchdog model showed acceptable average pairwise percent agreement, ranging from investigative reporting with an agreement of 76% to 98% for defense, support policies and activities.

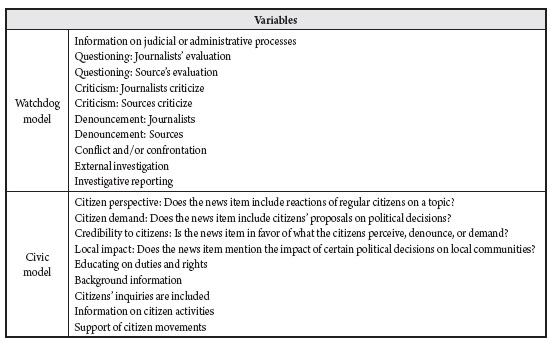

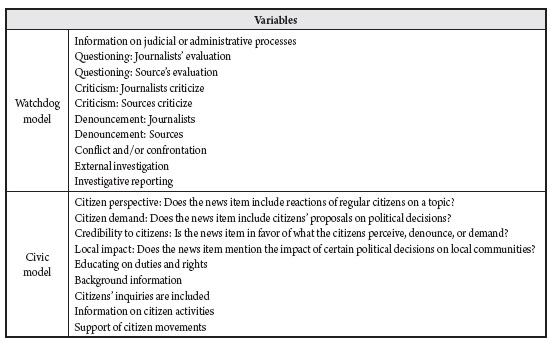

Content Categories. The coding manual included categories to measure each of the role performances as well as source use and reporting methods (see table 1). For the role performance items, Mellado (2015) was followed by coding on a presence (1) or absence (0) basis. Ten items were used to measure the watchdog model and nine items for the civic oriented model based on a previous developed codebook (Mellado, 2015; Hellmueller & Mellado, 2016) (see table 1). Since the analytical framework, on which this paper is based, provided a strong conceptual basis for predicting the two analyzed models of role performance but there was no previous empirical study on role performance in the US national press, we tested our hypothesized models using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). CFA was performed using Mplus 7.0. The model fit was assessed using the following criteria: chi-square value (χ2), the root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA) (smaller than .05), the comparative fit index (CFI) value (greater than .90), the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) value (greater than .90), and the weighted root mean squared residual (WRMR) (less than 1.0) (Schreiber, Nora, Stage, Barlow, & King, 2006). The indices calculated for the watchdog model provided an overall good fit to the data: (χ2) (21) = 150,2, p < .001, RMSEA = .040 [90% CI = .030: .049], CFI = .992, TLI = .989, WRMR = 1.202. In the case of the civic model, the indices calculated provided an overall good fit to the data: (χ2) (18) = 86,7, p < .001, RMSEA = .050 [90% CI = .042: .06], CFI = .884, TLI = .812, WRMR = 1.112.

Since the analyses showed satisfactory fit with our data, the items included in each model were recoded, so that higher compulsive scores of all items combined divided by the total amount of items (range: 0-1) would result in a final score for either the watchdog or the civic oriented model for each article. A higher score expressed higher presence of those journalistic role performance models. With this analyses strategy, assumptions were followed from journalistic role research that multiple roles can co-exists (e.g., Weaver et al., 2007; Mellado and Lagos, 2014).

Results

A total of 1,421 news stories were analyzed that were published on the national pages of The New York Times (N=373) The Los Angeles Times (N=227) Washington Post (N=364), USA Today (N=193), and Wall Street Journal (N=264).

The first research question asked how much the watchdog and civic oriented model manifested in the newspapers' coverage. According to the measured scores of 0 (null presence) to 1 (complete presence), the newspapers showed varied degrees of both the watchdog and civic oriented model (see table 2). Taken together, newspapers have a higher tendency to perform the civic-oriented model (M = .12) than the watchdog model (M= .09). Specifically, the civic-oriented model was found significantly more in The Los Angeles Times than the other newspapers (M=.23), with The New York Times and Washington Post following next (M=.13). Although at a lower rate, The Los Angeles Times and Washington Post showed the highest tendency for the watchdog model (M=.13) with The New York Times close behind (M=.11). USA Today and Wall Street Journal showed low levels of both models.

Table 1. Journalistic Role Performance Items

Table 2. Presence of Models

The first hypothesis dealt with the prominence of the watchdog and the civic oriented journalism models. It was assumed that stories employing watchdog or civic oriented journalism are given more prominence. To address this hypothesis, an independent-samples T Test was conducted to calculate the differences in how the placement of the news stories predicted the journalism model applied. Results illustrate that there is a significant difference in whether the civic oriented model was used on the front page or the inside pages (t = 7.01, df = 337, p < .001) as well as a significant difference in whether the watchdog model occurred on the front page or inside pages (t = 5.51, df = 355, p < .001). Descriptive results reveal higher expression of the civic model performance on the front page (M = .18, SD = .17) than on inside pages (M = .10, SD = .13). The same is true for the watchdog model. The prominence of the watchdog model is more visible and stronger expressed on the front pages (M = .12, SD = .12) than on the inside pages (M = .08, SD = 0.1).

The second hypothesis wanted to determine if there is a significant difference in story type and the expression of the journalism models in news content. To address this hypothesis, a one-way ANOVA was conducted to calculate the differences between story types such as articles, features, reportage, and brief and the expression of watchdog or the civic oriented journalism models. The results reveal that there are significant differences for the civic oriented journalism model (F(3, 1412) = 44.39, p < .001) as well as for the watchdog journalism model (F(3, 1414) = 28.00,p < .001). Bonferroni post hoc tests illustrate that features / chronicles are more likely to reflect the expression of civic oriented journalism (M = .20, SD = .18), than the story type of articles (M = .04, SD = .09), (p < .001). The same dynamic was found for the watchdog model. The expression of the watchdog model is higher in features/chronicles (M = .12, SD = .15) than in articles (M = .09, SD = .10), (p < .001).

The civic oriented journalism performance was mostly found in stories dealing with topics such as human rights (M = .35, SD = .15), demonstrations (M = .24 SD = .23), and religion (M = .22, SD = .18), whereas the highest visibility of the watchdog model was found in topics dealing with religion and churches (M = .17, SD = .19), government (M = .13, SD = .12) as well as police and crime (M = .14, SD = .11).

The third hypothesis dealt with sourcing as a contextualizing element of the civic oriented and the watchdog journalism models. It was assumed that source use would predict a particular journalistic role performance. To analyze this question, a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was calculated using civil sources, political sources, ordinary people sources, media sources, business sources, anonymous sources, and document sources as independent variables, and news articles' scores for civic oriented or watchdog model performance as dependent variables. Significant differences for the two models were found for the following source use: The use of expert sources (F= 9.11, p < .001,), as well as the use of political sources (F= 12.57, p < .001,), and the use of document sources (F= 14.30, p < .001,) significantly predicts the watchdog model.

Furthermore, articles including document sources were significantly more likely to predict the manifestation of the watchdog model (M=.12, SD=.12) than articles without document sources (M=.07, SD=.09). In addition, journalists quoting political party sources (M = .10, SD = .11) are significantly more likely to express the watchdog model in their reporting than journalists who are not quoting political sources (M = .04, SD = .09). On the other hand, journalists quoting ordinary people (M = .27, SD = .15) are significantly more likely to express the civic model in their reporting than journalists who are not quoting ordinary people (M = .04, SD = .07).

Discussion

This study tested the expression of journalists' use of the watchdog and civic oriented journalistic model in news stories in five major U.S. newspapers. This study is novel as it is one of the first to examine journalistic role conception from its practical perspective, from its manifestation in news (i.e., journalistic role performance). By examining role conception from its practical perspective, the study connects the inner workings of journalists—their normative stances as an expression of the individual level of analysis, i.e., gatekeeping theory (i.e., Shoemaker & Vos, 2009) with their external ties, the organizational output and routine practices of news organizations (i.e., with higher levels of gatekeeping procedures).

This study also provides understanding of how story elements, routine levels of newsroom influence, correlate to the civic or watchdog models, in that these models are found more prevalently on front pages versus inside pages of newspapers (Kim, 2012; Cassidy, 2006; Carpenter, 2008). This study therefore counters the argument that the civic oriented model is less suited to American journalism than it is to journalism in other parts of the world (Ahva, 2012) arguing instead that the routine levels of the gatekeeping process may in fact override American journalists' individual watchdog role conceptions resulting in civic oriented content. Given that the findings demonstrate that both models were found more often on the front page rather than the inside page, this study illustrates that indeed routine forces in journalism such as supervisors, sources, training, and peers on staff (Cassidy, 2006) are the routine forces that can predict role performance rather than individual level forces alone.

The topics covered and the sources used by the civic model are related to story type and, therefore it stands to reason that features and chronicles are commonly utilized over articles or briefs. Issues such as housing/infrastructure, social problems, demonstrations, and human rights necessitate the use of human sources and, as such, are more likely to be told from a human interest or soft news perspective rather than headline news that government official general warrant. Further research is needed to incorporate reporters' perceptions of the civic model and whether or not its conceived capacity can cover hard news issues.

Conversely, understanding whether or not mass audiences can fully accept the civic model used more prominently is important. While recent Pew research reveals that 70% of Americans feel the news is often influenced by organizations or powerful people (Pew Research Center, 2013), the same Pew poll reveals that one of the few commendations of journalists is their watchdog role when 68% of respondents agreed that the press stops authorities from doing things they should not be doing (Pew Research Center, 2013). Under this audience expectation, it is then fitting that topics covered by the watchdog model are frequently business and economy related and the sources used are predominantly government or state sources. However, what may seem surprising is that, despite the prevalence of political sources, religion was also heavily covered in the watchdog model.

While this study produced significant results relating to the watchdog and civic models, it is not without limitations. Even though newspapers are considered opinion leaders in journalism, it is also important to branch out to other media channels since publics seek out news from more than newspapers exclusively (Pew Research Center, 2013). While we have explained the expression of either the watchdog or the civic oriented model by story type, an interesting undertaking would be to extend this analysis to online news to investigate how much professionalism and public service expression can be found in stories published online by those same newspapers. This study, no doubt, opens the door for initiating a dialogue between the practice of journalism and its normative stance—by taking into account the context of gatekeeping procedures and their influence over the manifestation of the expression of journalistic roles in content.

References

Ahva, L. (2012). Public journalism and professional reflexivity. Journalism,14(6), 790-806.

Bennett, W.L. (2009). News. The politics of illusion. New York, NY: Pearson Education, Inc.

Bennett, W.L.; Lawrence, R.G. & Livingston, S. (2008). When the press fails: Political power and the news media from Iraq to Katrina. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Berkowitz, D.A. (2009). Reporters and their sources. In K. Wahl-Jorgensen & T. Hanitzsch (Eds.), The handbook of journalism Studies, 102-115.New York, NY:Routledge.

Berry, S.J. (2009). Watchdog journalism: The art of investigative reporting. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Bissell, K.L. (2000). A return to 'Mr. Gates': Photography and objectivity. Newspaper Research Journal, 21(3), 81.

Blumler, J. & Cushion, S. (2014). Normative perspectives on journalism studies: Stock-taking and future directions. Journalism: Theory Practice and Criticism, 15(3), 259-272.

Carlson, M. (2010). Embodying deep throat: Mark felt and the collective memory of Watergate.

Carpenter, S. (2008). How online citizen journalism publications and online newspapers utilize the objectivity and rely on external sources. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 85(3), 531-548.

Cassidy, W.P. (2006). Gatekeeping similar for online, print journalists. Newspaper Research Journal, 27(2), 6-23.

Collins, T.A. & Cooper, C.A. (2015). Making the cases "real": Newspaper coverage of U.S. Supreme Court cases 1953-2004. Political Communication, 32(1), 23-42. doi:10.1080/10584609.2013.879363

Cotter, C. (2010). News talk: Investigating the language of journalism. New York: NY, Cambridge University Press. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 27(3), 235-250.

De Burgh, H. (Ed.). (2006). Making journalists: Diverse models,global issues. New York, NY: Routledge.

Deuze, M. (2005). What is journalism? Professional identity and ideology of journalists reconsidered. Journalism, 6(4), 442-464.

De Witt, K. (1992, June 15). Watergate, then and now; Who was who in the cover-up and uncovering of Watergate. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/1992/06/15/us/watergate-then-and-now-who-was-who-in-the-cover-up-and-uncovering-of-watergate.html?action=click&module=Search®ion=searchResults%230&version=&url=http%3A%2F%2Fq [Date accessed: July 3, 2016]

Donsbach, W. (2008). Journalists' role perceptions. In W. Donsbach (ed.), The International Encyclopedia of Communication, 2605-10. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Entman, R.M. (2004). Projections of power: Framing news, public opinion, and U.S. foreign policy. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Evans, M. (2010). Framing international conflicts: Media coverage of fighting in the Middle East. International Journal of Media & Cultural Politics, 6(2), 209-233. doi:10.1386/mcp.6.2.209_1

Feldstein, M. (2006). A muckraking model investigative reporting cycles in American history. The Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics, 11(2), 105-120.

Ferguson, S. D. (2000). Researching the public opinion environment: Theories and methods (p. 56). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Inc.

Gil de Zúñiga, H. & Hinsley, A. (2013). The Press versus the public. Journalism Studies, 14(6), 926-942. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2012.744551

Glasser, T.L. & Ettema, J.S. (1989). Investigative journalism and the moral order. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 6(1), 1-20.

Glazier, R. A. & Boydstun, A.E. (2012). The president, the press, and the war: A tale of two framing agendas. Political Communication, 29, 428-446.

Gnisci, A.; Van Dalen, A. & Di Conza, A. (2014). Interviews in a polarized television market: The Anglo-American watchdog model put to the test. Political Communication, 31(1), 112-130. doi:10.1080/10584609.2012.747190

Graber, D. A., & Smith, J. M. (2005). Political communication faces the 21st century. Journal of Communication, 55(3), 479-507.

Hanitzsch, T. (2007). Deconstructing journalism culture: Toward a universal theory. Communication Theory, 17(4), 367-385.

Hanitzsch, T. (2011). Populist disseminators, detached watchdogs, critical change agents and opportunist facilitators. International Communication Gazette, 73(6), 477-494.

Harmon, M. & Muenchen, R. (2009). Semantic framing in the build-up to the Iraq war: Fox v. CNN and other U.S. broadcast news programs. ETC: A Review of General Semantics, 66(1), 12-26.

Hassid, J. (2011). Four models of the fourth estate: A typology of contemporary Chinese journalists. The China Quarterly, 208, 813-832.

Hellmueller, L., & Mellado, C. (2016). Journalistic Role Performance and the Networked Media Agenda: A Comparison between the United States and Chile (pp. 119-132). In L. Guo, & M. McCombs (Eds.), The Power of Information Networks: New Directions for Agenda Setting. New York: Routledge.

Ho, S.S.; Binder, A.R.; Becker, A.B.; Moy, P.; Scheufele, D.A.; Brossard, D. & Gunther, A.C. (2011). The role of perceptions of media bias in general and issue-specific political participation. Mass Communication & Society, 14(3), 343-374.

Hodgetts, D.; Chamberlain, K.; Scammell, M.; Karapu, R. & Nikora, L.W. (2008). Constructing health news: possibilities for a civic-oriented journalism. Health, 12(1), 43-66.

Kim, H.S. (2012). War journalists and forces of gatekeeping during the escalation and the de-escalation periods of the Iraq War .International Communication Gazette, 74(4), 323- 341. doi:10.1177/1748048512439815

Kumar, D. (2010). Framing Islam: The resurgence of Orientalism during the Bush II era. Journal of Communication Inquiry, 34(3), 254-277.

Kurpius, D.D. (2002). Sources and civic journalism: Changing patterns of reporting? Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 79(4), 853-866.

Lambeth, E.B.; Meyer, P.E. & Thorson, E. (1998). Assessing public journalism. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri.

Lewis, S.C. & Reese, S.D. (2009). What is the war on terror? Framing through the eyes of journalists. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 86(1), 85-102.

Lee, S.T. (2001). Public journalism and non-elite actors and sources. Newspaper Research Journal, 22(3), 92.

Marder, M. (1998). This is watch dog journalism. Nieman Reports, 52(2), 56.

Massey, B.L. & Haas, T. (2002). Does making journalism more public make a difference? A critical review of evaluative research on public journalism. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 79(3), 559-586.

McDevitt, M.; Gassaway, B.M. & Pérez, F.G. (2002). The making and unmaking of civic journalists: Influences of professional socialization. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 79(1), 87-100.

Mellado, C. (2015). Professional roles in news content: Six dimensions of journalistic role performance. Journalism Studies, 16, 596-614. doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2014.922276.

Mellado, C. & Lagos, C. (2014). Professional roles in news content: Analyzing journalistic performance in the Chilean national press. International Journal of Communication, 8, 23.

Mellado, C. & Van Dalen, A. (2014). Between rhetoric and practice: Explaining the gap between role conception and performance in journalism. Journalism Studies, 15(6), 859-878. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2013.838046

Mindich, D. (1998). Just the facts: How "objectivity" came to define American journalism (p. 4). New York, NY: New York University Press.

Ogle, D., Klemp, R. M., & McBride, B. (2007). Building literacy in social studies: Strategies for improving comprehension and critical thinking. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Pew Research Center. (2013, August 8). Amid criticism, support for media's 'watchdog' role stands out. Retrieved from http://www.peoplepress.org/2013/08/08/amid-criticism-support-for-medias-watchdog-role-stands-out/ [Date accessed: July 3, 2016]

Pinto, J. G. (2009). Diffusing and translating watchdog journalism. Media History, 15(1), 1-16.

Plaisance, P., & Skewes, E. A. (2003). Personal and professional dimensions of news work: Exploring the link between journalists' values and roles. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 80(4), 833-848.

Pottker, H. (2003). News and its communicative quality: the inverted pyramid-when and why did it appear? Journalism Studies, 4(4), 501.

Powell, K.A. (2011). Framing Islam: An analysis of U.S. media coverage of terrorism since 9/11. Communication Studies, 62(1), 90-112.

Riffe, D.; Aust, C. F. & Lacy, S. R. (1993). The effectiveness of random, consecutive day and constructed week sampling in newspaper content analysis. Journalism Quarterly, 70, 133-139.

Riffe, D.; Lacy, S. & Fico, F. (2005). Analyzing media messages: Using quantitative content analysis in research (2nd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Rosen, J. (1999). What are journalists for? New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Schreiber, J. B.; Nora, A.; Stage, F. K.; Barlow, E. A. & King, J. (2006). Reporting Structural Equation Modeling and Confirmatory Factor Analysis Results: A Review. The Journal of Educational Research, 99(6), 323-338.

Schultz, J. (1998). Reviving the fourth estate: Democracy, accountability and the media. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Shafer, R. & Aregood, R. (2012). Protecting journalists by applying the civic journalism model in developing countries. A case study of the Philippines. Media Asia, 39(2).

Shoemaker, P.J. & Reese, S.D. (1996). Mediating the message: Theories of influences on mass media content. 2nd ed. White Plains, NY: Longman.

Shoemaker, P.J. & Vos, T. (2009). Gatekeeping theory. Routledge.

Shoemaker, P.J.; Eichholz, M.; Kim, E. & Wrigley, B. (2001). Individual and routine forces in gatekeeping. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 78(2), 233-246.

Starkman, D. (2011). The watchdog that didn't bark: The financial crisis and the disappearance of investigative journalism. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Stephenson, D. (1998). How to succeed in Newspaper Journalism. London, UK: Kogan Page Publishers.

Strelitz, L. & Steenveld, L. (1998). The fifth estate: Media theory, watchdog of journalism. Ecquid Novi, 19(1), 100-110.

Voakes, P.S. (1999). Civic duties: Newspaper journalists' view on public journalism. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 76(4), 756-774.

Waisbord, S. (2000). Watchdog Journalism in South America: News, Accountability, and Democracy. New York: Columbia University Press.

Weaver, D. H. (ed.). (1998). The Global Journalist: News People around the World. New York, NY: Hampton Press.

Weaver, D.; Beam, R.A.; Brownlee, B.J.; Voakes, P. S. & Wilhoit, G.C. (2007). The American journalist in the 21st century. U.S. news people at the dawn of a new millennium. Mahweh, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Weaver, D. & Willnat, L. (Eds.). (2012). The global journalist in the 21st century (pp. 343-347). New York, NY: Routledge.

Willnat, L. & Weaver, D.H. (2014). The American journalist in the digital age: How journalists and the public think about U.S. journalism. Paper presented at the annual conference of AEJ, AEJMC, Montreal, August 2014.

Willnat, L.; Weaver, D.H. & Choi, J. (2013). The global journalist in the twenty-first century. Journalism Practice, 7(2), 163-183. doi:10.1080/17512786.2012.753210