|

Articles

Shinta Prastyanti 1

Retno Wulandari 2

Adhi Iman Sulaiman 3

1 ![]() 0000-0002-4998-7403. Universitas Jenderal Soedirman, Indonesia.

0000-0002-4998-7403. Universitas Jenderal Soedirman, Indonesia.

![]() shinta.prastyanti@unsoed.ac.id

shinta.prastyanti@unsoed.ac.id

2 ![]() 0000-0003-4341-4126. Universitas Muhammadiyah Yogyakarta, Indonesia.

0000-0003-4341-4126. Universitas Muhammadiyah Yogyakarta, Indonesia.

![]() retno.wulandari@umy.ac.id

retno.wulandari@umy.ac.id

3 ![]() 0000-0002-7439-9961. Universitas Jenderal Soedirman, Indonesia.

0000-0002-7439-9961. Universitas Jenderal Soedirman, Indonesia.

![]() adhi.sulaiman@unsoed.ac.id

adhi.sulaiman@unsoed.ac.id

Received: 15/11/2023

Submitted to peers: 06/12/2023

Accepted by peers: 16/07/2024

Approved: 06/08/2024

Para citar este artículo / to reference this article / para citar este artigo: Prastyanti, S., Wulandari, R., & Sulaiman, A. I. (2024). Participatory Development Communication Strategy of an Urban Farming Program in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Palabra Clave, 27(4), e27411. https://doi.org/10.5294/pacla.2024.27A11

Abstract

Participatory development communication strategies to enhance local food security in Yogyakarta, Indonesia, have made substantial progress through urban farming initiatives. This study examines how these strategies contribute to improving local food security by analyzing urban farming programs initiated by the city government. Urban farming, as a key innovation, has become increasingly important due to diminishing arable land and the need for sufficient nutritional intake in both quantity and quality, necessitating active community involvement. The research employs observations and in-depth interviews with leaders and members of farmers' groups, agricultural extensions, and the local Department of Agriculture and Food staff, reinforced by focus group discussions. Findings indicate that the communication strategy, rooted in a bottom-up participatory development communication approach from planning through evaluation, embodies community empowerment, making the success and sustainability of the program a shared responsibility. Despite some accomplishments, the initiative has not yet been adopted by all community members. The harvest is also limited to daily needs and has not greatly improved group members' income. The key to participatory development communication in the urban farming program is regularly scheduled meetings held by farmer groups as a participatory medium to manage activities.

Keywords: Community empowerment; farmers' groups; local food; participatory development communication; urban farming.

Resumen

Las estrategias de comunicación participativa para el desarrollo que tiene por objeto mejorar la seguridad alimentaria local en Yogyakarta, Indonesia, han logrado avances notables a través de las iniciativas de agricultura urbana. En este estudio se examina la forma en que estas estrategias contribuyen a mejorar la seguridad alimentaria local mediante el análisis de los programas de agricultura urbana llevados a cabo por el gobierno de la ciudad. La agricultura urbana, como innovación fundamental, ha adquirido cada vez mayor importancia debido a la disminución de las tierras cultivables y a la necesidad de una ingesta nutricional suficiente tanto en cantidad como en calidad, lo que requiere la participación de la comunidad. La investigación hace uso de observaciones y entrevistas en profundidad con líderes y miembros de grupos de agricultores, personal y extensiones agrícolas y con el personal del Departamento de Agricultura y Alimentación local y se complementa con debates de grupos focales. Los hallazgos indican que la estrategia de comunicación, arraigada en un enfoque ascendente de comunicación participativa para el desarrollo desde la planeación hasta la evaluación, encarna el empoderamiento de la comunidad, lo que hace del éxito y la sostenibilidad del programa una responsabilidad compartida. A pesar de algunos logros, la iniciativa aún no ha sido adoptada por todos los miembros de la comunidad. Por otra parte, la cosecha también se limita a las necesidades diarias y no ha mejorado de forma significativa los ingresos de los miembros del grupo. En conclusión, la clave para la comunicación participativa para el desarrollo dentro del programa de agricultura urbana son las reuniones periódicas que sostienen los grupos de agricultores como medio participativo para gestionar las actividades.

Palabras clave: Comunicación participativa para el desarrollo; grupos de agricultores; agricultura urbana.

Resumo

As estratégias de comunicação participativa para o desenvolvimento com o objetivo de melhorar a seguridade alimentar local em Yogyakarta, na Indonésia, tiveram um progresso notável por meio de iniciativas de agricultura urbana. Neste estudo, examina-se como essas estratégias contribuem para melhorar a seguridade alimentar local por meio da análise dos programas de agricultura urbana implementados pelo governo da cidade. A agricultura urbana, como uma inovação fundamental, tornou-se cada vez mais importante devido à redução das terras aráveis e à necessidade de uma ingestão nutricional suficiente, tanto em quantidade quanto em qualidade, o que exige a participação da comunidade. A pesquisa faz uso de observações e entrevistas aprofundadas com líderes e membros de grupos de agricultores, funcionários e extensões agrícolas, bem como funcionários do Departamento de Agricultura e Alimentação local, e é complementada por discussões em grupos focais. As descobertas indicam que a estratégia de comunicação, baseada em uma abordagem de comunicação participativa de baixo para cima para o desenvolvimento, do planejamento à avaliação, incorpora o empoderamento da comunidade, tornando o sucesso e a sustentabilidade do programa uma responsabilidade compartilhada. Apesar de algumas conquistas, a iniciativa ainda não foi adotada por todos os membros da comunidade. Além disso, a colheita também se limita às necessidades diárias e não melhorou significativamente a renda dos membros do grupo. Em conclusão, a chave para a comunicação participativa para o desenvolvimento dentro do programa de agricultura urbana são as reuniões regulares realizadas pelos grupos de agricultores como um meio participativo de gerenciar as atividades.

Palavras-chave: Comunicação participativa para o desenvolvimento; grupos de agricultores; agricultura urbana.

Introduction

Development communication is fundamentally based on the principle that developmental media and participatory communication focus on transforming community awareness and enhancing the effectiveness of institutions involved in the development process. Consequently, in conjunction with other academic disciplines, participatory development communication has contributed to sustainable development by involving communities in decision-making processes aimed at improving their living standards, particularly in the area of food security (Lennie & Tacchi, 2022; Manyozo, 2017; Samad & Padhy, 2018; Servaes, 2022; Yusoff et al., 2017).

Yogyakarta, Indonesia, is recognized as a significant national and international tourism destination with unique and appealing agricultural potential. Despite rapid developments in facilities, infrastructure, tourism destinations, and population growth, Yogyakarta has managed to maintain its agricultural activities. According to the Central Bureau of Statistics of Yogyakarta (2023), the available agricultural land spans 3,250 hectares, which includes 54 hectares of rice fields in 2020. This area decreased to 53 hectares in 2021 but increased by 1 hectare the following year. Agricultural land represents only 3 % of the total area of Yogyakarta. Conversely, the population growth rate has been increasing over this period, with the population rising from 373,589 in 2020 to 376,324 in the following year and further to 378,913 in 2022. This population growth impacts the increased demand for food. Additionally, Yogyakarta's numerous alleys, corridors, and walls may serve as alternative solutions to the limited agricultural land. These issues and potentials have prompted the Mayor of Yogyakarta to implement an urban farming program based on Yogyakarta Mayor Regulation No. 128 of 2021 concerning Farmer Institutions and Main Actors in Fisheries (The Office of Agricultural Extension of Yogyakarta City, 2022).

Urban farming is typically small-scale due to limited land availability. It aims to enhance food stock in terms of both quality and quantity while addressing the reduction of Green Open Spaces in the city, serving as a recreational outlet, improving air quality, and providing economic empowerment to enhance community well-being (Andiani et al., 2021; Huang, 2021; Poulsen et al., 2017; Sardiana, 2018; Sarwadi & Irwan, 2018).

In Yogyakarta, there are 276 farmer groups distributed across 14 sub-districts. However, not all these groups participate in the urban farming program, as some manage rice fields. The urban farming program aims to enhance food security by increasing the consumption of nutritious and safe food through alleys and vacant spaces for growing agricultural commodities. This program empowers community-established farmers' groups, the majority of which comprise women. The issue of women's empowerment is increasingly important across various sectors and affects awareness of gender inequality, fostering collective identity among women (de Carvalho & Bogus, 2020; Mandal, 2013).

Research on urban farming has been conducted by various scholars across many countries (Beacham et al., 2019; Carolan, 2019; Grebitus et al., 2020; Lotfi et al., 2020; Orsini, 2020; Petrovics & Giezen, 2021; Waddu-wage, 2021). Previous research also indicates that urban farming programs have successfully implemented participatory approaches in other regional or international areas, such as in Bogor, Indonesia, France, Uganda, India, and Thailand (Clerino & Fargo-Lelievre, 2020; Odoi, 2017; Oktarina et al., 2022; Sereenonchai & Arunrat, 2023; Touri, 2016). However, research on participatory development communication strategies within urban farming programs holds significant academic and practical interest, as food security is not solely the government's responsibility but heavily relies on community involvement. An additional benefit is the potential to build unity, strengthen social capital, and enhance the capabilities of active community members, ultimately correlating with the program's success as an integral part of sustainable development efforts.

The process and involvement of stakeholders in the program and the challenges and difficulties encountered are critical questions in addressing the study objectives. This study aims to analyze how participatory development communication strategies in urban farming programs in Yogyakarta contribute to reducing local food insecurity. It is also possible that these strategies could be applied to other cities in Indonesia. This program is unique because it combines top-down and bottom-up approaches. On the other hand, participatory communication is viewed by Freire (1970) as a grassroots initiative that articulates, visualizes, and presents a community and does not separate it from traditional culture.

Literature Review

The evolution of development communication theory for social change cannot be isolated from the effect of Westernization and colonial viewpoints, which merged ideas from Europe, the United States, Latin America, and other regions while originally disregarding ideas from periphery nations. It must be acknowledged that participatory and democratic development communication is a significant contribution from the Latin American experience based on aspects such as structural settings, oral traditions, poverty, and disparities in various sectors (Aguirre Alvis, 2014; Barranquero, 2017; Dagron, 2010).

Critiques of the old development paradigm have led to the emergence of participatory development communication strategies, positioning them as central to the third development paradigm. This paradigm is characterized by stakeholder integration processes that can transform the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of communities, enabling voluntary engagement in development processes (Barranquero-Carretero & Sáez-Baeza, 2014; Bessette, 2020; Musakophas & Polnigongit, 2017). Participatory development communication is a valuable approach for enhancing community participation as it allows for a deeper understanding of community needs through knowledge sharing and empowerment, and it facilitates social cohesion and integration (Barranquero, 2017; Bassey & Etika, 2019; Incio et al., 2021; John & Etika, 2019).

The implementation of participatory development communication strategies is an intriguing subject for researchers due to its dialogic nature, which is accompanied by practices of freedom, placing humans as subjects, enabling social transformation, and promoting sustainability (Carrick et al., 2023; Suzina et al., 2020; Touri, 2016; Willy & Holm-Muller, 2013). Nevertheless, participation in participatory development communication strategies is not merely an end and a means to an end but also requires support from individuals, various institutions, and media (Ali & Sonderling, 2017;

Koutsou et al., 2014; Molale & Fourie, 2023). It is also marked by the emergence of various media forms, including new media, in line with the Information and Communications Technology (ICT) trend that has defined the shift in dominant paradigms. The advent of new media positions communities not merely as passive beneficiaries of development communication processes but also as active participants, including message producers (Breuer et al., 2018; Cogo et al., 2015; Patil, 2019; Plenkovic & Mustie, 2016).

Farmers' groups also play a role in utilizing the latest information and communication technology, although access to this technology is often more significant for entertainment and general information-seeking rather than for agriculture-related information (Mashi et al., 2022; Prastyanti et al., 2020; Rajabi et al., 2021; Rumata & Sakinah, 2020; Sekaranom et al., 2021; Zhu et al., 2022).

The development of agriculture in Yogyakarta occurs in buffer areas around the city center that border other regions such as Magelang, Kulon Progo, Klaten, and Surakarta, which still have extensive agricultural land and communities that rely on farming. However, the city center of Yogyakarta has transformed into a hub for tourism and culinary destinations, resulting in a significant reduction in agricultural land. The urban farming program strategy implemented by local and village governments aims to meet the daily needs of families and farmer or women's farmer groups.

Women's empowerment in Indonesia is unique in its own right. On the one hand, it provides opportunities for women to enhance their capacities and contributes to various aspects of life, with notable opportunities for female representation in legislative elections up to 30 % (Nadia, 2022; Stiyaningsih & Wicaksono, 2017; Widiyanti et al., 2018). On the other hand, the patriarchal system remains deeply entrenched in the majority of Indonesian society. Even the increase in education has not proven sufficient to empower women in Indonesia in household decision-making, community participation, or asset ownership (Samarakoon & Parinduri, 2015). In contrast, Akter et al. (2017) and Ang and Lai (2023) state that the agricultural sector in Indonesia remains predominantly male-dominated despite women's equal access to productive resources and decision-making autonomy.

Women farmers' groups in Indonesia generally emerge from the awareness and motivation developed by village governments or empowerment activists or from women actively participating in community social institutions such as Family Welfare Empowerment and Integrated Service Posts. These groups initially started as social activities to meet their own needs and those of their families or groups. Subsequently, these women farmers' groups have expanded their efforts to generate additional income for families as a side job and, in some cases, have become a primary occupation (Handoko et al., 2024; Utami et al., 2024; Windiasih et al., 2023). In addition to women's empowerment, the integrated development of urban farming systems is also a significant indicator of sustainable urban development (Andini et al., 2021; Degefa et al., 2021; Horst et al., 2017; Prasada & Masyhuri, 2020).

Research Methods

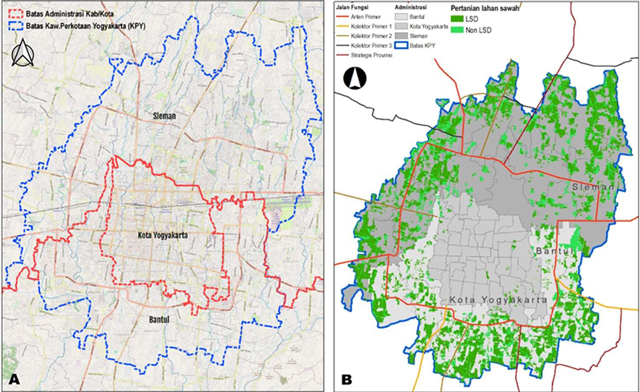

This research holds significant, unique, and important ethical implications when the urban farming program becomes part of the spirit of Yogyakarta's urban farming groups to meet the daily needs of families and farmer groups (Figure 1). Academically and practically, it can serve as a study for developing urban farming as edu-tourism.

Figure 1. A) Urban Area of Yogyakarta; B) Distribution of Rice Fields in Yogyakarta

Source: Firmansyah et al. (2024)

The 2022-2023 research employs a qualitative research method with a case study approach. This study was conducted in four sub-districts: Rejowinangun, Danurejan, Mantrijeron, and Wirobrajan. These sub-districts were chosen because each has unique characteristics compared to other sub-districts. The success of community participation in the urban farming program in Rejowinangun is seen from a quantitative aspect, namely the formation of many farmer groups that spread to the neighborhood level. From a qualitative aspect, Danurejan stands out for organizing various agricultural activities and actively utilizing social media to publicize them. In Mantrijeron, urban farming activities are organized with a sectoral division of responsibilities, where each farmer group is responsible for managing one vegetable/fruit alley. Unlike the other three sub-districts, the urban farming program in Wirobrajan aims not only to fulfill family nutritional intake but also to serve as edu-tourism.

Data were gathered through in-depth interviews and observations, reinforced by focus group discussions (FGDs), to explore data not expressed during individual interviews with farmer groups from these four sub-districts. The research informants were key actors active in the urban farming program since its inception and were selected through purposive sampling. Four focus group discussions were conducted and attended by twenty-four participants, including group leaders and members from the four subdistricts, for six per sub-district. In-depth interviews were conducted with thirty-eight informants, including four group leaders, twenty-four group members, four government agricultural extensions, four independent agricultural extensions, and two local Agriculture Office staff members. The matrix of informants, information obtained, and data collection techniques is shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Matrix of Research Informants, Types of Information, and Data Collection Techniques

Informant |

Data obtained |

Data collection techniques |

Yogyakarta Agriculture Office Staff |

Implementation of urban gardening activities Policies within the urban gardening program Collaborations undertaken |

Interviews |

Agricultural Extension |

Educational activities conducted Media used for educational purposes |

Interviews, Documentation, Observation |

Group Leader |

Activities of the farmers' group and participation of its members |

Interviews, Documentation |

Group Members |

Participation of members in activities Communication processes among members of the farmers' group |

Interviews, Documentation, Observation, FGD |

Source: Own elaboration.

After data collection through several techniques, important data supporting the research were sorted. The collected data were then verified and triangulated to check their validity. The next stage involved categorization, data presentation, and conclusion. Qualitative data analysis involves a process of data collection, sorting, and reduction. Data are further deepened and refined through verification and clarification with informants, followed by triangulating data sources, theories, and concepts, which are then categorized and summarized (Denzin & Lincoln, 2018; Dõringer, 2021; Lester et al., 2022; McGrath et al., 2018). The researcher verbally presented the study to the participants, and participation was entirely voluntary.

Results and Discussion

The Yogyakarta region, which is relatively small and densely populated, requires precise strategies to maintain agricultural sustainability and economic growth. To address this, agricultural policy strategies in Yogyakarta are based on accurate data obtained through agricultural censuses, allowing for the preservation of limited agricultural land, the exploration of potential, and innovation ( Jogjaprov.go.id, 2023). Facts and data also indicate that participatory development communication has been implemented by the community in Yogyakarta, particularly by urban farmers' groups, through the Musyawarah Perencanaan Pembangunan (Development Planning Deliberation) forum mechanism, which operates from the village or sub-district level to the district and provincial levels. The results of this forum include proposals that prioritize addressing issues, needs, and the development of socio-economic and environmental resources within the community, one of which is the urban farming program.

Although the urban farming program in Yogyakarta initially began as a top-down model, the community, through farmers' groups, has played a substantial role in participating and influencing the program's success. It is implemented hierarchically from the sub-district to the village, hamlet, and neighborhood levels. Each farmer group consists of 10-40 residents, though only about half of the members are active for various reasons such as work commitments and household responsibilities. Participation in the program encompasses planning, implementation, evaluation, and utilization of results. In some farmer groups, agricultural extension actively provides advice, while others do not. More advanced groups are often led by extension agents, providing them with broader networks and easier access to support facilities in the urban farming program.

Participatory development communication, characterized by a more bottom-up approach, involves voluntary community participation in designing, implementing, and evaluating development programs according to their needs and issues. It can be initiated by the government, facilitators, academics, or community groups themselves and contributes to enhancing community capabilities (Oshimi & Yamaguchi, 2023; Sugito et al., 2019; Sulaiman et al., 2019).

The urban farming program in Yogyakarta was carried out using larger plots, such as communal gardens, followed by vacant spaces like alleys, walls, passages, and fences for planting various crops, including vegetables, medicinal plants, and fruits. The program employs vertical and tiered planting strategies using wall planters, pots, polybags, and repurposed items like gallon containers, bottles, jerry cans, and other discarded materials. Planting is done by farmer group members with a variety of species, as noted by a member of the Women Farmers Group. Informant Y stated: "Farmer groups rarely plant only one crop type, but usually plant several types together such as mustard greens, spinach, pak choy, biofarmaka, water spinach, celery, and ornamental plants." The diversity of crops planted was also noted by a member of the farmers' group, Mr. Z: "The crops are of various types, such as water spinach, mustard greens, lettuce, celery, and spinach."

Group meetings are conducted according to each group's schedule, typically once a month on the 25th and led by the group leader. The topics discussed are determined by the farmer group members themselves, such as the planning and implementation process, including planting media, seeding, planting locations, watering, pest control, and harvesting methods, as well as evaluating the program. In this meeting, each group member can freely express their input, complaints, and obstacles and collectively solve problems faced by the farmer group.

In addition to regular meetings, communication among group members is also conducted through WhatsApp groups. This social media platform is expected to facilitate faster communication, especially for urgent issues that need immediate attention. Participatory development communication is characterized by its dialogic, egalitarian, and open nature, allowing all parties to voice their aspirations regarding agreed-upon needs and issues. It seeks to find shared solutions for community economic empowerment (Lemke, 2016; Madsen, 2018; Sulaiman & Ahmadi, 2020). The success of participatory communication relies on local aspects, both in terms of communication technology and interpersonal channels (Chirwa, 2023; Chutjaraskul, 2021; Mossie et al., 2021; Ndlovu et al., 2022). In line with these perspectives, Anwar et al. (2020) and Bonatti et al. (2018) argue that efforts to enhance food security and improve community well-being can be achieved through social communication patterns as a means to interact with the community and understand the interrelatedness of various issues, including those related to food security.

Besides planting, farmers' groups also process agricultural products into higher-value items, such as spinach chips, syrups, eggplant drinks, traditional herbal medicine (jamu), wingko (a traditional Javanese snack), and others. However, this product diversification has not yet significantly increased the income of group members, as production is limited to fulfilling orders rather than regular manufacturing.

In addition, farmers' groups collaborate with waste banks to produce their own fertilizer by utilizing household kitchen waste, which is channeled through pipes from each house. The waste is left to decompose for two to three months, resulting in liquid organic fertilizer that can be applied to plants. The residue from decomposition can also be used as solid organic fertilizer. Using self-produced fertilizer reduces operational costs in the urban farming program. As beneficiaries and key stakeholders in the urban farming program, farmers' groups play a significant role in increasing productivity, income, and product prices and lowering production and transportation costs (Abdul-Rahaman & Abdulai, 2020; Bachke, 2019; Mutanyi, 2019).

The urban farming program in Yogyakarta faces various challenges, including seed supply, planting media, fertilizers, post-harvest management, and marketing. Another challenge is the low economic value of harvested commodities, primarily for daily consumption and reducing household expenses. The limited farming skills of group members, many of whom lack an agricultural background, pose a specific challenge to the program. Furthermore, Arabzadeh et al. (2023), Kullu et al. (2020), Sroka et al. (2021), and Takagi et al. (2020) argue that lack of information on farming and inadequate guidance are significant challenges.

Nonetheless, successful examples of urban farming programs can be found in the Wirobrajan sub-district. The Winongo Asri Farmers' Group in Wirobrajan has innovated by transforming the urban farming program into an attractive educational tourism initiative (Figure 2). This is in line with the research findings conducted by Andiani et al. (2021), Asrul et al. (2023), and Barokah et al. (2023) that urban farming can also become a tourist destination, packaged as edu-tourism and agro-tourism. Another example is the Danurejan sub-district, led by the Gemah Ripah Adult Farmers' Group, which organizes various activities and exhibitions and publishes through social media. This utilization of social media is unique to this farmers' group.

Figure 2. Exhibition of Urban Farming Program Results in Yogyakarta

Source: Authors' archives.

The research also reveals that the program has not yet attracted the entire community. It appears more appealing to those aged 45-60 than younger age groups. Contrary to these findings, Lapple and Rensburg (2013) suggest that younger people are more likely to adopt agricultural innovations. The urban farming program in Yogyakarta is also predominantly found in lower-income neighborhoods rather than in more economically stable residential areas, though valid data comparing the program's implementation in different areas is lacking (Figure 3). The program significantly impacts low-income communities more due to their stronger economic motivation and interest, aligning with the views of Diekmann et al. (2018) and Kirby et al. (2021). Conversely, some argue that the socio-economic characteristics of residents do not significantly affect the acceptance of urban farming but correlate with the type of urban farming practiced.

In addition to improving family nutrition, the urban farming program in Yogyakarta is expected to foster social relationships within the community and utilize leisure time for beneficial activities, as stated by a local Agricultural Office staff member, Mr. X:

There are greater benefits, such as fostering a sense of community and relaxation among residents. Moreover, it can develop an area, for example, turning vacant land initially used as a dump into a green space planted by the community or farmers' groups.

Figure 3. Urban Farming in Yogyakarta

Source: Authors' archives.

The development of urban farming in Yogyakarta is undertaken not only by farmers' groups but also by extension officers. The role of the Yogyakarta City Agriculture and Food Department is to initiate the urban farming program, supported by agricultural extension officers who implement policies through public awareness campaigns while simultaneously empowering the community. Although extension services encompass technical, educational, and social elements, they often present challenges. Nonetheless, humane extension services can significantly contribute to the success of farmers (Cournane et al., 2016; Lu & Grundy, 2017). However, at the inception of the extension program, access to and satisfaction with extension services significantly increased among female farmers' groups. Female farmers face additional challenges related to productivity, and extension services are significantly correlated with farmers' productivity and capability improvement (Abbeam et al., 2018; Buehren et al., 2019; Ragasa & Mazunda, 2018).

Enhancing community capabilities through participatory development communication is a strategy to achieve consistent communication based on decisions regarding multiple communication activities within the community. This communication strategy is built upon four objectives: motivation, education, information dissemination, and making essential information the basis for decision-making. It involves the planned dissemination of messages that are informative, persuasive, and instructive to the target audience while bridging cultural gaps among the actors involved in the communication process (Browning et al., 2020; Syed Alwi et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2022; Winczorek, 2022).

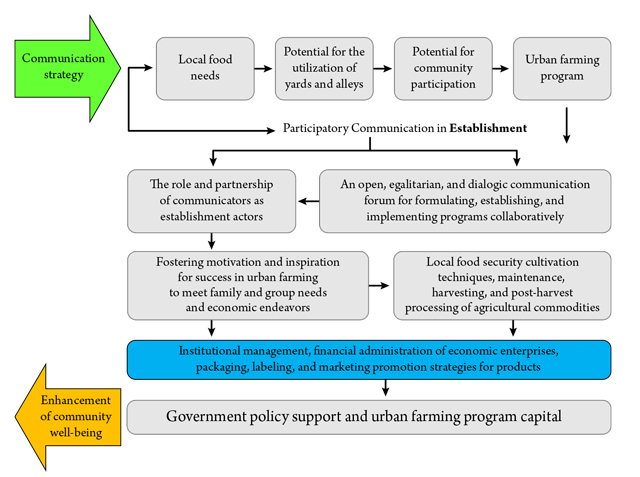

The design of a participatory development communication strategy for the urban farming program can be realized through the following approaches:

(1) Involvement, roles, and partnerships of all related stakeholders to establish coordination, consolidation, and synergy, thereby strengthening institutions and ensuring program success (McGahan, 2021; Pellizzoni et al., 2020; Pollock et al., 2019; Rane et al., 2021; Rosyadi et al., 2020).

(2) Participatory development communication forums encompassing planning, consensus-building, implementation, and program evaluation ensure that the program becomes collectively owned and a shared responsibility.

(3) Identification and analysis of community issues: While initiated by the local government, the program also focuses on identifying and analyzing the community's issues, needs, and potential, as well as those of farmers' groups.

(4) Comprehensive government policy support. Farmers' groups consistently receive empowerment programs, including training and support, to enhance their knowledge and skills in local food security and post-harvest practices. The sustainability of the urban farming program driven by farmers' groups needs supportive policies and collaboration from various stakeholders (Bisaga et al., 2019).

(5) Local food security empowerment program. This includes extension and training as a form of community development and enhancement of capabilities in urban farming.

Enhancing community capabilities through a participatory development communication strategy for the success of the urban farming program in Yogyakarta involves several key aspects (Figure 4): (1) Improving motivation and awareness of the program's benefits; (2) Cultivation techniques for local food crops in yards and gardens; (3) Maintenance and harvesting techniques; (4) Post-harvest processing to create added value for families and groups; (5) Institutional development, management, and financial administration for business groups; (6) Techniques for packaging, labeling, and marketing promotion to enhance the economic value of local food security and post-harvest products; (7) Involvement of experts and instructors from academic and business sectors; (8) Comprehensive financial support from local and village governments, as well as the establishment of voluntary business capital from the community and group members, such as cooperatives.

Figure 4. Design of a Participatory Development Communication Strategy for Urban Farming in Yogyakarta, Indonesia

Source: Own elaboration.

Conclusions

While the local government initiated the urban farming program, the involvement of farmers' groups from the planning stage to the program's evaluation and utilization of the results phase exemplifies the participatory development communication strategy. This approach is evident in several activities, such as planting, producing fertilizers using household waste, harvesting, and other initiatives, as well as the active participation of farmers' groups in group meetings and training and extension activities held by agricultural extension agents. These activities aim to support local food security while simultaneously enhancing community capabilities.

The strategy of participatory development communication among farmer group members in regular meetings and employing diverse communication channels within the community has the potential to motivate, educate, disseminate information, and provide a foundational basis for decision-making that contributes significantly to local food security and the advancement of sustainable development initiatives.

However, the program still faces various difficulties and challenges, including seed supply, fertilizers, the low economic value of commodities, and others. This program has also not been adopted by the entire community and has not yet increased the income of group members. In contrast, regular meetings conducted by farmers' groups are the key to participatory medium.

References

Abbeam, G. D., Ehiakpor, D. S., & Aidoo, R. (2018). Agricultural extension and its effects on farm productivity and income: insight from Northern Ghana. Agriculture & Food Security, 7(74), 2-10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40066-018-0225-x

Abdul-Rahaman, A., & Abdulai, A. (2020). Farmer groups, collective marketing and smallholder farm performance in rural Ghana. Journal of Agribusiness in Developing and Emerging Economies, 10(5), 511-527. https://doi.org/10.1108/JADEE-07-2019-0095

Aguirre Alvis, J. L. (2014). Development Communication in Latin America. In Handbook of Communication for Development and Social Change. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Akter, S., Rutsaert, P., Luis, J., Htwe, N. M., San, S. S., Raharjo, B., & Pustika, A. (2017). Women's empowerment and gender equity in agriculture: A different perspective from Southeast Asia. Food Policy, 69, 270-279. https://doi.org/10.1016/jfoodpol.2017.05.003

Ali, A. C., & Sonderling, S. (2017). Factors Affecting Participatory Communication for Development: The Case of a Local Development Organization in Ethiopia. Jurnal Komunikasi Malaysian Journal of Communication, 33(1), 80-97. https://doi.org/10.17576/JKM-JC-2017-3301-06

Andiani, R., Witjaksono, R., Sari, W. A., Mustika, E., Hernandau, H. D., Puspadjati, F. A., Annastana, V., & Hia, Y. A. (2021). The Sustainability of Household-based Pertanian perkotaan in Yogyakarta City. In Proceedings of 1st International Conference on Sustainable Agricultural Socio-economics, Agribusiness, and Rural Development (pp. 229-234). https://doi.org/10.2991/aebmr.k.211214.032

Andini, M., Dewi, O. C., & Marwati, A. (2021). Pertanian perkotaan During the Pandemic and Its Effect on Everyday Life. International Journal of Built Environment and Scientific Research, 5(1), 51-62. https://doi.org/10.24853/ijbesr.5.1.51-62

Ang, C. W., & Lai, S. W. (2023). Women's Empowerment in Malaysia and Indonesia: The Autonomy of Women in Household Decision-Making. Pertanika Journal of Social Sciences & Humanities, 31 (2), 903-916. http://pertanika2.upm.edu.my/resources/files/Pertanika%20PAPERS/JSSH%20Vol.%2031%20(2)%20Jun.%202023/22%20JSSH-8608-2022.pdf

Anwar, R. K., Rizal, E., & Lusiana, E. (2020). Social Communication of Farmers in Establishing Food Security Recovery. Temali: Jurnal Pembangunan Sosial, 3(1), 18-38. https://doi.org/10.15575/jt.v3i1.7482

Arabzadeh, V., Miettinen, P., Kotilainen, T., Herranen, P., Karakoc, A., Kummu, M., & Rautkari, L. (2023). Urban vertical farming with a large wind power share and optimised electricity costs. Applied Energy, 331, 120416. https://doi.org/10.1016Zj.apenergy.2022.120416

Asrul, N. R., Irham, I., & Jamhari. (2023). Motivation of Urban People Towards the Sustainability of Urban Farming in Yogyakarta City. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Smart and Innovative Agriculture (ICoSIA 2022) (pp. 124-135). Atlantis Press. https://doi.org/10.2991/978-94-6463-122-7_12

Bachke, M. (2019). Do farmers' organizations enhance the welfare ofsmallholders? Findings from the Mozambican national agricultural survey. Food Policy, 89, 101792. https://doi.org/10.1016/jfood-pol.2019.101792

Barokah, U., Rahayu, W., & Antriyandarti, E. (2023). The Role Of Urban Farming To Household Food Security In The Surakarta City, Indonesia. Agrisocionomics: Jurnal Sosial Ekonomi Pertanian, 7(3), 526-538. https://doi.org/10.14710/agrisocionomics.v7i3.15942

Barranquero, A. (2017). Rediscovering the Latin Americas Roots of Participatory Communication for Social Change. Westminster Papers in Communication and Culture, 8(1), 154-177. https://doi.org/10.16997/wpcc.179

Barranquero-Carretero, A., & Sáez-Baeza, C. (2014). Communication and good living. The decolonial and ecological critique to communication for development and social change. Palabra Clave, 18(1), 41-82. https://doi.org/10.5294/pacla.2015.18.1.3

Bassey, G., & Etika, D. (2019). Sustainable Development through Participatory Communication. The Journal of Development Communication, 30(2), 60-71. http://jdc.journals.unisel.edu.my/index.php/jdc/article/view/154

Beacham, A. M., Fickers, L. H., & Monaghan, J. M. (2019). Vertical farming: a summary of approaches to growing skywards. The Journal of Horticultural Science and Biotechnology, 94(3), 277-283. https://doi.org/10.1080/14620316.2019.1574214

Bessette, G. (2020). Participatory Development Communication and Natural Resources Management. In J. Servaes (Ed.) Handbook of Communication for Development and Social Change (pp. 1141-1154). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-2014-3_71

Bisaga, I., Parikh, P., & Loggia, C. (2019). Challenges and Opportunities for Sustainable Urban Farming in South African Low-Income Settlements: A Case Study in Durban. Sustainability, 11(20), 5660. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11205660

Bonatti, B., Schlindwein, I., Lana, M., Bundala, N., Sieber, S., & Rybak, C. (2018). Innovative educational tools development for food security: Engaging community voices in Tanzania. Futures, 96, 79-89. https://doi.org/10.1016/jfutures.2017.11.008

Breuer, A., Blomenkemper, L., Kliesch, S., Salzer, F., Schádler, M., Sch-weinfurth, V., & Virchow, S. (2018). The potential of ICT-supported participatory communication interventions to challenge local power dynamics: Lessons from the case of Togo. The Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries, 84(3), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1002/isd2.12026

Browning, N., Lee, E., Park, Y. E., Kim, T., & Collins, R. (2020). Muting or Meddling? Advocacy as a Relational Communication Strategy Affecting Organization-Public Relationships and Stakeholder Response. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 97(4), 1026-1053. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699020916810

Buehren, N., Goldstein, M., Molina, E., & Vaillant, J. (2019). The impact of strengthening agricultural extension services on women farmers: Evidence from Ethiopia. Agricultural Economics. The Journal of the International Association of Agricultural Economics, 50(4), 407-419. https://doi.org/10.1111/agec.12499

Carolan, M. (2019). Urban Farming Is Going High Tech. Digital Urban Farming's Links to Gentrification and Land Use. Journal of the American Planning Association, 86(1), 47-59. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2019.1660205

Carrick, J., Bell, B., Fitzsimmons, C., Gray, T., & Stewart, G. (2023). Principles and practical criteria for effective participatory environmental planning and decision-making. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 66(14), 2854-2877. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2022.2086857

Central Bureau of Statistics of Yogyakarta. (2023). Yogyakarta Municipality in Figures, 2023.

Chirwa, J. A. (2023). The Challenge of Doing Participatory Communication in Disaster Risk Reduction in Malawi. Global Media, 21 (63), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.36648/1550-7521.21.63.370

Chutjaraskul, V. (2021). Participatory Communication for Sustainable Community Development in Nong Mek Subdistrict, Na Chueak District, Maha Sarakham Province. Annals of the Romanian Society for Cell Biology, 1157-1166.

Clerino, P., & Fargo-Lelievre, A. (2020). Formalizing Objectives and Criteria for Urban Agriculture Sustainability with a Participatory Approach. Sustainability, 12(18), 7503. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187503

Cogo, D., Dutra-Brignol, L., & Fragoso, S. (2015). Everyday Practices for Access to ICT: Another Way of Understanding Digital Inclusion. Palabra Clave, 18(1), 156-183. https://doi.org/10.5294/pacla.2015.18.1.7

Cournane, F. C., Cain, T., Greenhalgh, S., & Samarsinghe. (2016). Attitudes of a farming community towards urban growth and rural fragmentation—An Auckland case study. Land Use Policy, 58, 241-250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.07.031

Dagron, G. A. (2006). Knowledge, communication, development: a perspective from Latin America. Development in Practice, 16(6), 593-602. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614520600958272

de Carvalho, L. M., & Bogus, C. M. (2020). Gender and Social Justice in Urban Agriculture: The Network of Agroecological and Peripheral Female Urban Farmers from São Paulo. Social Sciences, 9(8), 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9080127

Degefa, B., Albedwawi, A. M. M., & Alazeezib, M. S. (2021). The Study of the Practice of Growing Food at Home in the UAE: Role in Household Food Security & Wellbeing and Implication for the Development of Urban Farming. Emirates Journal of Food and Agriculture, 33 (6), 465-74. https://doi.org/10.9755/ejfa.2021.v33.i6.2712

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2018). The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research. SAGE Publications, Inc.

Diekmann, L. O., Gray, L. C., & Baker, B. A. (2018). Growing 'good food': urban gardens, culturally acceptable produce and food security. Renewable Agriculture and Food System, 35(2), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742170518000388

Dõringer, S. (2021). 'The problem-centred expert interview'. Combining qualitative interviewing approaches for investigating implicit expert knowledge. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 24(3), 265-278. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2020.1766777

Firmansyah, F., Raharja, A. B., Priyandoko, Z., & Nirbhaya, Y. (2024). Analisis Indeks Keterancaman Lahan Sawah di Kawasan Perkotaan Yogyakarta. Mimbar Agribisnis: Jurnal Pemikiran Masyarakat Ilmiah Berwawasan Agribisnis, 10(1), 59-70. https://doi.org/10.25157/ma.v10i1.11416

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogía del oprimido. Tierra Nueva.

Grebitus, C., Chenarides, L., Muenich, R., & Mahalov, A. (2020). Consumers' Perception of Urban Farming-An Exploratory Study. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 4(79), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2020.00079

Handoko, W., Sulaiman, A. I., Sugito, T., & Sabiq, A. (2024). Empowering Former Women Migrant Workers: Enhancing Socio-Economic Opportunities and Inclusion for Sustainable Development. Academic Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies, 13(1), 199. https://doi.org/10.36941/ajis-2024-0015

Horst, M., McClintock, N., & Hoey, L. (2017). The Intersection of Planning, Urban farming, and Food Justice: A Review of the Literature. Journal of the American Planning Association, 83(3), 277-295. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2017.1322914

Huang, S.-M. (2021). Urban farming as a Transformative Planning Practice: The Contested New Territories in Hong Kong. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 41(1), 32-47. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X18772084

Incio, F. A. R., Navarro, E. R., Arellano, E. G. R., & Melendez, L. V. (2021). Participatory communication as a key strategy in the construction of citizenship. Linguistics and Culture Review, 5(51), 890-900. https://doi.org/10.21744/lingcure.v5nS1.1473

Jogjaprov.go.id. (2023). Sensus Pertanian 2023 Pintu Menuju Kebijakan Pertanian Yang Lebih Baik. https://jogjaprov.go.id/berita/sensus-pertanian-2023-pintu-menuju-kebijakan-pertanian-yang-lebih-baik

John, G., & Etika, D. N. (2019). Sustainable Development Through Participatory Communication: An Assessment of Selected Community Project in Cross River State, Nigeria. Journal of Development Communication, 30(1), 1-12. https://jdc.journals.unisel.edu.my/index.php/jdc/article/view/154

Kirby, C. K., Specht, K., Kamper, R. F., Hawes, J. K., Cohen, N., Caputo, S., Lieva, R. T., Lelievre, A., Ponizy, L., Schoen, V., & Blythe, V. (2021). Differences in motivations and social impacts across urban agriculture types: Case studies in Europe and the US. Landscape and Urban Planning, 212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2021.104110

Koutsou, S., Partalidou, M., & Ragkos, A. (2014). Young farmers' social capital in Greece: Trust levels and collective actions. Journal of Rural Studies, 34(April), 204-211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2014.02.002

Kullu, P., Majeedullah, S., Pranay, P. V. S., & Yakub, B. (2020). Smart Urban farming (Entrepreneurship through EPICS). Procedia Computer Science, I72, 452-459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2020.05.098

Lapple, D., & Rensburg, T. V. (2013). Adopt ion of organic farming: Are there differences between early and late adoption? Ecological Economics, 70(7), 1406-1414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2011.03.002

Lemke, J. (2016). From the Alleys to City Hall: An Examination of Participatory Communication and Empowerment among Homeless Activists in Oregon. Journal of Communication Inquiry, 40(3), 267-286. https://doi.org/10.1177/0196859916646045

Lennie, J., & Tacchi, J. (2022). Evaluating Communication for Development: A Framework for Social Change. Routledge.

Lester, J. N., Cho, Y., & Lochmiller, C. R. (2022). Learning to Do Qualitative Data Analysis: A Starting Point. Human Resource Development Review, 19(1), 94-106. https://doi.org/10.1177/15344843209038

Lotfi, Y. A., Refaat, M., El Attar, M., & Salam, A. A. (2020). Vertical gardens as a restorative tool in urban spaces of New Cairo. Ain Shams Engineering Journal, 11(3), 839-848. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asej.2019.12.004

Lu, C., & Grundy, S. (2017). Pertanian perkotaan and Vertical Farming. Encyclopedia of Sustainable Technologies, 3, 393-402. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-409548-9.10184-8

Mandal, K. C. (2013). Concept and Types of Women Empowerment. International Forum of Teaching and Studies, 9(2), 17-30.

Madsen, V. T. (2018). Participatory communication on internal social media - a dream or reality? Findings from two exploratory studies of coworkers as communicators. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 23(4), 614-628. https://doi.org/10.1108/CCIJ-04-2018-0039

Manyozo, L. (2017). Communicating Development with Communities (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315180526

Mashi, S. A., Inkani, A. I., & Oghenejabor, O. D. (2022). Determinants of awareness levels of climate smart agricultural technologies and practices ofurban farmers in Kuje, Abuja, Nigeria. Technology in Society, 70, 102030. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2022.102030

McGahan, A. M. (2021). Integrating Insights from the Resource-Based View ofthe Firm Into the New Stakeholder Theory. Journal of Management, 47(7), 1734-1756. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206320987282

McGrath, C., Palmgren, P. J., & Liljedahl, M. (2018). Twelve tips for conducting qualitative research interviews. Medical Teacher, 41 (9), 1002-1006. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2018.1497149

Molale, T., & Fourie, L. (2023). A six-step framework for participatory communication and institutionalized participation in South Africa's municipal IDP processes. Development in Practice, 33(6), 675-686. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2022.2104810

Mossie, M., Gerezgiher, A., & Ayalew, Z. (2021). Food security effects of smallholders' participation in apple and mango value chains in north-western Ethiopia. Agriculture & Food Security, 10, 47. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40066-021-00310-z

Musakophas, R., & Polnigongit, W. (2017). Current and future studies on participatory communication in Thailand. Kasetsart Journal of Social Sciences, 38(1), 68-73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kjss.2016.01.011

Mutanyi, S. (2019). The effect of collective action on smallholder income and asset holdings in Kenya. World Development Perspectives, 14(June), 100099. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wdp.2019.02.010

Nadia, S. (2022). Pemberdayaan Perempuan untuk Kesetaraan. Kementerian Keuangan https://www.djkn.kemenkeu.go.id/kpknl-pontianak/baca-artikel/15732/Pemberdayaan-Perempuan-untuk-Kesetaraan.html

Ndlovu, P. N., Thamaga-Chitja, J. M., & Ojo, T. O. (2022). Impact of value chain participation on household food insecurity among smallholder vegetable farmers in Swayimane KwaZulu-Natal. Scientific African, 16(July), e01168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sciaf.2022.e01168

Odoi, N. (2017). The information behaviour of Ugandan banana farmers in the context of participatory development communication. Information Research, 22(3), paper 759. http://InformationR.net/ir/22-3/paper759.html

Oktarina, S., Sumardjo, S., Purnaningsih, N., & Hapsari, D. R. (2022). Participatory Communication and Affecting Factors on Empowering Women Farmers in The Pertanian perkotaan Program at Bogor City and Bogor Regency. NYIMAK. Journal of Communication, 6(1), 77-93. http://dx.doi.org/10.31000/nyimak.v6i1.5156

Orsini, F. (2020). Innovation and sustainability in urban farming: the path forward (Editorial). Journal of Consumer Protection and Food Safety, 15, 203-204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00003-020-01293-y

Oshimi, D., & Yamaguchi, S. (2023). Leveraging strategies of recurring non-mega sporting events for host community development: a multiple-case study approach. Sport, Business and Management, 13(1), 19-36. https://doi.org/10.1108/SBM-06-2021-0071

Patil, D. A. (2019). Participatory Communication Approach for RD: Evidence from Two Grassroots CR Stations in Rural India. Asia-Pacific Journal of Rural Development, 29(1), 98-110. https://doi.org/10.1177/1018529119860623

Pellizzoni, E., Trabucchi, D., Frattini, F., Buganza, T., & Di Benedetto, A. (2020). Leveraging stakeholders' knowledge in new service development: a dynamic approach. Journal of Knowledge Management, 24(2), 415-438. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-10-2019-0532

Petrovics, G., & Giezen, M. (2021). Planning for sustainable urban food systems: an analysis of the up-scaling potential of vertical farming. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 65(5), 785-808. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2021.1903404

Plenkovic, M., & Mustie, D. (2016). The New Media Paradigm of Participatory Communication as a Result of Participatory Culture of Digital Media. Media, Culture and Public Relations, 7(2), 143-149. https://hrcak.srce.hr/176502

Pollock, A., Campbell, P., Struthers, C., Synnot, A., Nunn, J., Hill, S., Goodare, H., Morris, J., Watts, C., & Morely, R. (2019). Development of the ACTIVE framework to describe stakeholder involvement in systematic reviews. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 24(4), 245-255. https://doi.org/10.1177/1355819619841647

Poulsen, M. N., Neff, R. A., & Winch, P. J. (2017). The multifunctionality of urban farming: perceived benefits for neighborhood improvement. The International Journal of Justice and Sustainability, 22 (11), 1411-1427. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2017.1357686

Prasada, I. Y., & Masyhuri, M. (2020). Factors Affecting Farmers' Perception toward Agricultural Land Sustainability in Peri-Urban Areas of Pekalongan City. Caraka Tani: Journal of Sustainable Agriculture, 35(2), 203-212. https://doi.org/10.20961/carakatani.v35i2.31918

Prastyanti, S., Subejo, S., & Sulhan, M. (2020). New Media Access and Use for Triggering the Farmers Capability Improvement in Central Java Indonesia. Humanities and Social Science Research, 3(1), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.30560/hssr.v3n1p1

Ragasa, C., & Mazunda. (2018). The impact of agricultural extension services in the context of a heavily subsidized input system: The case of Malawi. World Development, 105, 25-47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.12.004

Rajabi, S., Lashgarara, F., Chowdhury, A., Rashvand, H., & Daghighi, H. S. (2021). Improving Effectiveness of Rural Information and Communication Technology Offices: The Case of Qazvin Province in Iran. Asia-Pacific Journal of Rural Development, 31(1), 108-126. https://doi.org/10.1177/10185291211027455

Rane, S. B., Thakker, S. V., & Kant, R. (2021). Stakeholders' involvement in green supply chain: a perspective of blockchain IoT-integrated architecture. Management of Environmental Quality, 32(6), 1166-1191. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEQ-11-2019-0248

Rosyadi, S., Kusuma, A. S., Fitrah, E., Haryanto, A., & Adawiyah, W. (2020). The Multi-Stakeholder's Role in an Integrated Mentoring Strategi for SMEs in the Creative Economy Sector. SAGE Open, 10(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244020963604

Rumata, V. M., & Sakinah, A. M. (2020). The Impact of Internet Information and Communication Literacy and Overload, as Well as Social Influence, on ICT Adoption by Rural Communities. Asia-Pacific Journal of Rural Development, 30(1-2), 155-174. https://doi.org/10.1177/1018529120977250

Samad, H., & Padhy, M. K. (2018). Poverty Alleviation, Food Security and Environmental Sustainability: The Contribution of Participatory Development Communication. The Journal of Development Communication, 26(2), 14. http://jdc.journals.unisel.edu.my/index.php/jdc/article/view/37

Samarakoon, S., & Parinduri, R. A. (2015). Does Education Empower Women? Evidence from Indonesia. World Development, 66, 428-442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.09.002

Sardiana, I. K. (2018). The Study of Development of Urban farming Agrotourism Subak-Irrigation-Based in Sanur Tourism Area, Denpasar City, Bali. Journal of Indonesian Tourism and Development Studies, 6(1), 33-40. https://doi.org/10.21776/ub.jitode.2018.006.01.05

Sarwadi, A., & Irwan, S. N. R. (2018). Pemanfaatan Area Pekarangan Sebagai Lanskap Produktif di Permukiman Perkotaan. Tesa Arsitektur, Journal of Architectural Discourses, 16(1), 40-48. https://doi.org/10.24167/tesa.v16i1.1213

Sekaranom, A. B., Nurjani, E., & Nucifera, F. (2021). Agricultural Climate Change Adaptation in Kebumen, Central Java, Indonesia. Sustainability, 13(13), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137069

Sereenonchai, P., & Arunrat, N. (2023). Urban Agriculture in Thailand: Adoption Factors and Communication Guidelines to Promote Long-Term Practice. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010001

Servaes, J. (2022). Communication for development and social change (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003170563-4

Sroka, W., Bojarszczuk, J., Satola, L., Szczepañska, B., Sulewski, P., Lisek, S., Luty, L., & Ziolo, M. (2021). Understanding residents' acceptance of professional urban and peri-urban farming: A socio-economic study in Polish metropolitan areas. Land Use Policy, 109, 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1016/jlandusepol.2021.105599

Stiyaningsih, H, & Wicaksono F. (2017). Impact of women's empowerment on infant mortality in Indonesia. Kesmas: National Public Health Journal, 11(4), 185-191. https://doi.org/10.21109/kesmas.v11i4.1259

Sugito, T., Sulaiman, A. I., Sabiq, A., Faozanudin, M., & Kuncoro, B. (2019). Community empowerment strategi of coastal border based on ecotourism. Masyarakat, Kebudayaan Dan Politik, 32(4), 363-377. https://doi.org/10.20473/mkp.V32I42019.363-377

Sulaiman, A. I., & Ahmadi, D. (2020). Empowerment Communication in an Islamic Boarding School as a Medium of Harmonization. Jurnal Komunikasi: Malaysian Journal of Communication, 36(4), 323-338. https://doi.org/10.17576/JKMJC-2020-3604-20

Sulaiman, A. I., Chusmeru, C., & Kuncoro, B. (2019). The Educational Tourism (Edutourism) Development Through Community Empowerment Based on Local Wisdom and Food Security. InternationalEducational Research, 2(3), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.30560/ier.v2n3p1

Suzina, A. C., Tufte, T., & Jiménez-Martínez, C. (2020). Special issue: The legacy of Paulo Freire. Contemporary reflections on participatory communication and civil society development in Brazil and beyond. International Communication Gazette, 82(5), 407-410. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048520943687

Syed Alwi, S. F., Balmer, J. M. T., Stoian, M.-C., & Kitchen, P. J. (2022). Introducing integrated hybrid communication: the nexus linking marketing communication and corporate communication. Qualitative Market Research, 25(4), 405-432. https://doi.org/10.1108/QMR-09-2021-0123

Takagi, C., Purnomo, S. H., & Kim, M. K. (2020). Adopting Smart Agriculture among organic farmers in Taiwan. Asian Journal of Technology Innovation, 29(2), 180-195. https://doi.org/10.1080/19761597.2020.1797514

The Office of Agricultural Extension of Yogyakarta City. (2022). The Office of Agricultural Extension Profile.

Touri, M. (2016). Development communication in alternative food networks: empowering Indian farmers through global market relations. The Journal of International Communication, 22(2), 209-228. https://doi.org/10.1080/13216597.2016.1175366

Utami, W., Sulaiman, A. I., Windiasih, R., & Sari, L. K. (2024). Participation ofSocio-Economic Empowerment Groups in Improving the Economy in Rural Areas. Technium Sustainability, 7, 54-66. https://doi.org/10.47577/sustainability.v7i.11407

Wadduwage, S. (2021). Drivers of peri-urban farmers' land-use decisions: an analysis of factors and characteristics. Journal of Land Use Science, 16(3), 273-290. https://doi.org/10.1080/1747423X.2021.1922525

Wang, H., Jia, M., Xiang, Y., & Lan, Y. (2022). Social Performance Feedback and Firm Communication Strategy. Journal of Management, 48(8), 2382-2420. https://doi.org/10.1177/01492063211042266

Widiyanti, E., Pudjihardjo, P., & Saputra, P. M. A. (2018). Tackling Poverty through Women Empowerment: The Role of Social Capital in Indonesian Women's Cooperative. Jurnal Ekonomi dan Studi Pembangunan, 10(1), 44-55. http://dx.doi.org/10.17977/um-002v10i12018p044

Willy, D. K., & Holm-Müller, K. (2013). Social influence and collective action effects on farm level soil conservation effort in rural Kenya. Ecological Economics, 90(June), 94-103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2013.03.008

Yusoff, N. H., Mohd Hussain, M. R., & Tukiman, I. (2017). Roles of Community Towards Urban Farming Activities. Planning Malaysi. Journal of the Malaysian Institute of Plannersa, 15(1), 271-278. https://doi.org/10.21837/pm.v15i1.243

Winczorek, J. (2022). Moral communication and legal uncertainty in small and medium enterprises. Kybernetes, 51 (5), 1666-1691. https://doi.org/10.1108/K-02-2021-0125

Windiasih, R., Sari, L. K., Prastyanti, S., Sulaiman, A. I., & Sugito, T. (2023). Women Farmers Group Participation in Empowering Local Food Security. International Journal Of Community Service, 3(3), 186-194. https://doi.org/10.51601/ijcs.v3i3.200

Zhu, Q, Zhu, C., Peng, C., & Bai, J. (2022). Can information and communication technologies boost rural households' income and narrow the rural income disparity in China? China Economic Quarterly International, 2(3), 202-214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceqi.2022.08.003