|

Articulos

Ezequiel Ramón-Pinat1

1 ![]() 0000-0003-1050-6497. Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Spain.

0000-0003-1050-6497. Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Spain.

![]() ezequiel.Ramon@uab.cat

ezequiel.Ramon@uab.cat

* This research derives from a dissertation titled "El derecho a la vivienda en los medios sociales y en la prensa: La Plataforma de Afectados por la Hipoteca (PAH) y los desahucios" submitted to Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona (UAB). Available at http://hdl.handle.net/10803/672536

** Esta investigación se derivó de la tesis "El derecho a la vivienda en los medios sociales y en la prensa: La Plataforma de Afectados por la Hipoteca (PAH) y los desahucios" sometida a la Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona (UAB). Disponible en: http://hdl.handle.net/l0803/672536

*** Esta investigação resultou da tese "El derecho a la vivienda en los medios sociales y en la prensa: La Plataforma de Afectados por la Hipoteca (PAH) y los desahucios" apresentada à Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona (UAB). Disponível em: http://hdl.handle.net/10803/672536

Received: 14/11/2023

Submitted to peers: 11/12/2023

Approved by peers: 09/01/2024

Accepted: 05/02/2024

Para citar este artículo / to reference this article / para citar este artigo: Ramón-Pinat, E. (2024). Barricades against Evictions: Coexistence of Short- and Longterm Frames in the Housing Movement on Facebook and Twitter. Palabra Clave, 27(2),e2723. https://doi.org/10.5294/pacla.2024.27.2.3

Abstract

Social movements fight to change society's roots and challenge entrenched cultural frameworks. At the same time, however, they must attend to everyday activism and protests that constitute a clear and pragmatic mobilization goal. This article analyzes the case of a movement for decent housing on social media called Platform for Those Affected by Mortgages (PAH). This organization fights to guarantee universal access to housing, a recurrent problem in large cities. It grew in 2010 when the subprime mortgage crisis broke out in the United States. The bursting of the real estate bubble built up at that time had a global impact, pushing other markets. On the one hand, the movement has to change entrenched cognitive frameworks that say property must be bought and its loss is the individual's responsibility. On the other hand, it must coordinate and try to gather as many people as possible to stop the evictions that occur every day. Twitter seems crucial for daily mobilization in this double logic, while Facebook allows for more complex narratives. The methodology used was a framing analysis of the content published on the organization's official Facebook and Twitter accounts. Although these should be understood as overlapping layers, the movement is often trapped in a narrative that it does not want. By highlighting specific cases, it leads to an understanding that access to housing does not affect most of society.

Keywords: Social media; housing needs; right to housing; social movement; urban areas; social conflict.

Resumen

Los movimientos sociales luchan por cambiar las raíces de la sociedad, por desafiar marcos culturales arraigados. Al mismo tiempo, sin embargo, deben atender al activismo cotidiano, a las protestas que constituyen un objetivo claro y pragmático de la movilización. Este artículo analiza el caso del movimiento por una vivienda digna denominado Plataforma de Afectados por la Hipoteca (PAH) en las redes sociales. Esta organización lucha por garantizar el acceso universal a la vivienda, un problema recurrente en las grandes ciudades, y tuvo su auge en 2010, tras estallar la crisis de las hipotecas "subprime" en Estados Unidos. La explosión de la burbuja inmobiliaria que se generó en aquel entonces tuvo consecuencias mundiales, lo que terminó afectando a otros mercados. Por un lado, el movimiento tiene que cambiar marcos cognitivos arraigados que dicen que la propiedad hay que comprarla y que su pérdida es responsabilidad individual. Por otro lado, debe coordinarse e intentar reunir al mayor número de personas posible para detener los desahucios que se producen cada día. En esta doble lógica, Twitter parece ser crucial para la movilización diaria, mientras que Facebook permite narrativas más complejas. La metodología utilizada consistió en un análisis de marcos de los contenidos publicados en las cuentas oficiales de la organización en Facebook y Twitter. Aunque deben entenderse como capas superpuestas, el movimiento a menudo se ve atrapado en una narrativa que no es la que desea. Al destacar casos concretos, se logra entender que el acceso a la vivienda no afecta a la mayor parte de la sociedad.

Palabras clave: Redes sociales; necesidad de vivienda; derecho a la vivienda; movimiento social; zona urbana; conflicto social.

Resumo

Os movimentos sociais lutam para mudar as raízes da sociedade, para desafiar estruturas culturais arraigadas. Ao mesmo tempo, no entanto, eles precisam atender ao ativismo cotidiano, aos protestos que constituem uma meta clara e pragmática de mobilização. Neste artigo, analisa-se o caso do movimento por moradia digna chamado "Plataforma de Afectados por la Hipoteca" nas redes sociais. Essa organização luta para garantir o acesso universal à moradia, um problema recorrente nas grandes cidades, e teve seu boom em 2010, após a eclosão da crise das hipotecas subprime nos Estados Unidos. O estouro da bolha imobiliária naquela época teve consequências globais, que acabaram afetando outros mercados. Por um lado, o movimento precisa mudar as estruturas cognitivas arraigadas que dizem que a propriedade deve ser comprada e que sua perda é uma responsabilidade individual. Por outro lado, ele deve coordenar e tentar reunir o maior número possível de pessoas para impedir os despejos que ocorrem todos os dias. Nessa lógica dupla, o Twitter parece ser crucial para a mobilização diária, enquanto o Facebook permite narrativas mais complexas. A metodologia usada consistiu em uma análise da estrutura do conteúdo publicado nas contas oficiais da organização no Facebook e no Twitter. Embora devam ser entendidas como camadas sobrepostas, o movimento muitas vezes fica preso em uma narrativa que não é a que ele deseja. Ao destacar casos específicos, é possível entender que o acesso à moradia não afeta a maioria da sociedade.

Palavras-chave: Redes sociais; necessidade de moradia; direito à moradia; movimento social; área urbana; conflito social.

Introduction

The concept of digital activism encompasses a wide range of definitions. The largest consider the possession of fixed and mobile devices with Internet access as a form of participation. Then, with greater commitment, we find various forms of hacktivism, where the network is the final object of power, the battlefield, through denial-of-service attacks, battles to impose hashtags, or the defense of open-source programs. Other more committed concepts can also be found, referring to using digital media to achieve political goals (Gerbaudo, 2017). Currently, digital activism is being studied in a wide range of disciplines, from anthropology, sociology, and political science to, as in this case, media studies and journalism.

The technological determinism in the postulates of the first generation of scholars who analyzed the phenomenon of collective mobilization on the Internet contrasts with the most recent conclusions, which move in the opposite direction. The field has thus produced a rich corpus, an aspect that makes it as diverse as it is disparate, with a wide variety of epistemologies and applied points of view. Political and sociological research focuses mainly on the structures of mobilization and political opportunities, as well as the processes of information framing and diffusion, including the role of media, while cultural studies approaches emphasize the broader contexts in which digital activism takes place (Kaun & Uldam, 2018). The new currents analyzing this new form of activism are, in a sense, updating the postulates formulated decades ago by the Anglo-Saxon and continental European schools.

Drawing on this European cultural tradition, Paolo Gerbaudo and Emiliano Treré (2015), among others, call for studies that focus on the construction of collective identity in new groups. They denounce the dominance of the tradition of resource mobilization in organizational and strategic aspects and quantitative analyses facilitated by massive data. In this new form of mobilization, identity is emphasized as a binding substance because, unlike in the labor movement of the last century, joint struggle generally does not have pragmatic benefits such as an increase in income. Sharing a common identity among the participants is a key mobilizing element.

Contrary to the tendency of quantitative studies to provide a static overview of protest, this new cultural current, aided by the fluidity and transience of digital communication and the postmodern era, focuses on processes rather than outcomes. Moving away from the pragmatic analysis of strategies, it is, in some ways, a continuation of the school that focuses on the microdynamics of collective action and escapes the myopia of the concrete. As W. Lance Bennett (2012) points out about individualization and mobilization: "Social fragmentation and the decline of group loyalties have led to an era of personalized politics, in which individually expressive personal frames of action displace collective frames of action in many protest causes" (p. 20).

Both the "political opportunity" and "resource mobilization" currents have placed the concept of organizational communication under an instrumental dimension, a belt of messages that can be used or discarded. The movements would exist a priori and would not be influenced by communicative dynamics. They use an instrumental approach applied to contemporary mobilization, emphasizing aspects related to the organizational structure and the possibilities offered by the cheapening of resources to the detriment of symbolic and interrelational aspects.

Focusing too much on technologies and their use in the movements of the digital age has the consequence of falling into positions close to technological determinism, ignoring the aspects that surround participation but are fundamental and without which they would not materialize; they would remain at the mere wish of the promoters who emphasize the possibilities of the Internet as a space beyond the control of states, where geographical and economic barriers are eliminated. They value the apparent cheapness of communication and the absence of intermediation, which ignores the influence of algorithms without considering the interference of governments and corporations.

In this paradigm, the Internet is seen as a new public space where political, social, and economic interaction is fully engaged, physical location is irrelevant, and anonymity and multiple identities enhance activism (Machado, 2007). As Treré (2019) points out, analyses based solely on big data lead to a new "digital positivism" that ignores how algorithmically mediated environments have the power to restructure collective action and organizational dynamics radically. Far from being neutral, social media make the very socialization they offer and facilitate increasingly technical.

Paolo Gerbaudo (2019a) distinguishes two phases of digital activism. The first implies a countercultural politics of resistance from the margins of the hegemonic space, and the second conceives it as a political mainstream space in which protests crystallize. This shift can also be framed within the first wave of technological determinism, which saw the Internet as a regenerative instrument of politics and a way to increase youth participation. More recently, in the opposite sense, its obstacles have been highlighted: the arbitrariness of logarithms, the spread of false news, and the proliferation of bots, which make it difficult for the message of movements to prevail amid so much noise.

Is the Internet a Facilitator or a Handicap?

Vincent Crone and Jeroen Post (2015) identify four ways this technological determinism manifests itself in digital collective action. This logic treats social media as having a homogeneous and undifferentiated character that can only be used effectively. Social media would be articulated as particularly powerful, global, and interactive media. Within this argument, four defining characteristics repeatedly appear in the analyzed corpus:

(1) time - the effects of social media are direct and immediate; (2) space - social media transcend natural barriers; (3) hierarchy - social media equalize media and power relations; and (4) amplification - social media invite and equalize personal relationships. (Crone & Post, 2015, p. 876)

In this sense, from technological determinism, digital social media have been treated as alternative media, ignoring that they are owned by large corporations with a consequent search for economic benefits behind them, dominated by the power of algorithms, the "bubble filter" applied to activists and pollution, rather than clean input to decision-making that sabotages political campaigns. Paolo Gerbaudo (2019b) highlights the curtailment of "digital freedoms," given the weakness of the individual in the face of corporations and the state, of new forms of online surveillance that threaten individual freedom. The spread of fake news and the "hijacking" of hashtags make it impossible to meet and share, and thus, the manipulation of the media contributes to a decrease in trust, an increase in the circulation of false information, and greater radicalization.

The innovative practices of social movements, which began to use new technologies in their acts of protest and platforms such as Facebook and Twitter to disseminate their messages to their supporters, also gave rise to a wave of academic research supported by information technology. This new research method has been called the "computational turn" by Zeynep Tufekci (2014). This integration into the communicative repertoires of organizations has resulted in a renewal, albeit partial, of the theoretical tools for understanding the dynamics of network movements. This implies a significant increase in the application of quantitative methods, "data mining," to the vast amounts of information related to the protests that can be extracted from social media platforms, with more or less difficulty.

The Internet has played a vital role in almost every democratic transition in recent decades. However, when its role is studied, its limitations are often underestimated, starting with the fact that ICT use is not universal, being popular only among the youngest segments of the Asian population, with medium incomes and schooling. Other factors remain silent in the discussion of the Arab Spring, such as the impact of military aid, the geopolitical role of the country concerned, its economic dependence on institutions such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, and the neocolonial network of subjugation. These external conditions suspend or minimize the internal dynamics of the countries. These factors also help explain why some misnamed "Internet revolutions" succeed and others do not, even when the conditions are similar (Howard, 2010).

Another aspect ignored in movement studies is that social media do not belong exclusively to them but have a place among many other actors. Within this communicative dynamic, the flow of ideas and information is, to some extent, allowed globally. The fact that it is virtual has made it more difficult to control and repress, or rather, it has caused the repressive structures of states to rapidly develop new control and censorship mechanisms to adapt to the new scenario.

Cristian Quijada (2014), analyzing a wave of protests from the Chilean student movement, notes that despite being able to offer counter-framings to the hegemonic discourse, a significant part of the content posted on Facebook was simply a repackaging of content that appeared in the traditional press, questioning to what extent the dynamics that existed before the virtual era are currently being reproduced. However, articulating modes of struggle is not spontaneous or immediate but requires a process of constitution in the long term (Hardt & Negri, 2018).

Class identity cannot be assumed as something given and cannot configure the political struggle on its basis. However, its heterogeneous composition must be investigated, that is, who comprises it today, and framed in a political operation of constitution (Hardt & Negri, 2018). The Internet represents a barrier rather than an opportunity in identity construction, diluting the need to share a common physical space, accentuated by telecommuting during the COVID -19 pandemic. New jobs such as raiders, Amazon delivery drivers, or Uber drivers are the visible face of the precariousness of employment in the Internet age, the difficulty of creating bonds of solidarity, and the everyday struggle in large Western cities.

Concerning this relationship between virtuality and physical materialization, Andrew Chadwick (2007) points to what he calls "organizational hybridization," in which the processes of hybridization undertaken by social movements have been adopted by traditional parties and stakeholders. This new form of organization exists only in a hybrid form and could not function without the help of the Internet. Instead of considering the displacement of some channels by other different ones, we must understand it as an ecosystem in which media from different sources coexist and interact simultaneously (Quintana & Tascón, 2012).

In any case, social media are crucial to explaining mobilization, as individuals do not make decisions in a social vacuum. However, digitally mediated networks can be more challenging to manage, have looser ties, and are less receptive to the framing that movements themselves want to disclose. On the other hand, network users can dispose of content asynchronously and project physical participation in the background with the various causes and organizations they support, although this does not necessarily trigger mobilization on the streets (Walgrave et al., 2011).

Participation and Pseudo-participation

The late 1990s saw a gradual increase in interest in the Internet among communication scholars. Scholars focused on the Internet itself regarding the policies that govern it and its use, to the detriment of the application of traditional theories of media effects (Kim & Weaver, 2002). Three decades later, there is still a call for an intrinsic theory of the Internet that addresses its effects and how to improve them, along with the development of a toolkit of new concepts and theories (Fuchs, 2011, 2018a; Kim & Weaver, 2002; Lovink, 2004, 2016).

An initial euphoria about the emancipatory potential of the decentralized medium was pointed out by techno-fixated academics, who emphasized the horizontal-participatory structure and the opportunity for anyone to post what they want without filters. Subsequently, several critical voices emerged simultaneously as a process of concentration began. Fuchs et al. (2010) point out that it is not just a matter of developing a social theory of the Internet but a critical social theory of the network that helps to understand how computing in general, and the use of the Internet and the World Wide Web in particular, can help to improve the situation of humanity in order to build a better world. They reject out of hand the claim that it has become more social. They argue that this path is necessary to help scholars and citizens better understand social and Internet sociality.

The lack of a sociology of and for Web 2.0 means that most definitions come from marketing or remain unresolved. On the other hand, apart from claiming the development of a new theory adapted to the new characteristics, the postulates are claimed from a critical paradigm typical of the first Frankfurt School in the most innovative cases, and even from the more orthodox Marxism, rejecting empirical social phenomenology or the study of the web. Fuchs et al. (2010) proclaim knowledge as a triple dynamic process of cognition, communication, and cooperation within this current of thought.

In this sense, the notion of a network refers to its qualities as a technosocial system capable of enhancing human cognition, communication, and cooperation. Cognition must be understood here as a necessary precondition for communication and as a precondition for the emergence of cooperation. That is, to cooperate, we need to communicate and to communicate, we need to know. The difference between Web 2.0 and the previous network is not based on an evolutionary chronological distinction but rather on an analytical one. While all collaborative processes require communication and cognition, not all cognition and communication processes lead to collaboration (Fuchs et al., 2010).

Even in initiatives like Wikipedia, which is often held up as a mirror of what a social web should be, open-source development, or multiplayer online gaming, social stratification and hierarchical class arrangements remain within social collaboration systems. On the other hand, the structural functionalist school of sociology even argues that social stratification is beneficial to the stability of contemporary societies. From a Weberian perspective, in which stratification occurs due to differences in status and power, the rise of an administrator class establishment somewhat predicted the stratification of wiki society (Kittur et al., 2007).

For the reasons outlined above, the Wikipedia platform deserves the attention of the academic field for its relevance to the point that the rest of Web 2.0 would probably be like it if it had not turned to a fully commercial purpose. On the contrary, Wikipedia is a paradigmatic site of the same genre, offering users the free opportunity to interact or collaborate. Its output is the product of a social network dialogue that leads to creating user-generated content in a virtual community instead of sites where consumers are limited to passively viewing content created for them.

However, when this type of site began to appear, it was not a sudden success; on the contrary, its unusual form meant that it had to wait for the adaptation of the users, their trust, and complicity to succeed. While the first debates on the use of digital social networks focused on aspects such as online social interaction, the sharing of talents through the network, the creation of new relationships on Facebook, dialogues through blogs, or even the contribution of collective knowledge by editing Wikipedia, the spirit at the birth of the Internet, before the explosion of Web 2.0, was already focused on being a collaborative medium, a place where participants could meet and interact.

According to the companies' self-description, social networks are developed for free expression, exchange, communication, and community. According to Christian Fuchs (2018b), this image of the platforms is aligned with the notion of the social in bourgeois social theory, from a Durkheimian perspective, in which "the social" means exerting an external constraint on the individual. Therefore, any expression is social to the extent that it involves the thoughts and behaviors of others. In other words, each post on Facebook or Twitter is social because it has the potential to introduce the thoughts and behaviors of other users, even if no one responds.

To return to Weber's concept and apply it to Facebook and Twitter, an action is social if it takes into account, and is therefore oriented towards, the behavior of others. Putting ourselves in Max Weber's shoes, Facebook and Twitter would be social to the extent that users react, respond, and comment on other participants' tweets or publications, in the case of Facebook. According to the Durkheimian and Weberian understanding of the "social," the sociability proclaimed by the companies themselves would thus have a place. Christian Fuchs (2018b), on the other hand, rejects this image and refers to the platforms as "antisocial social media," where the commercial strategies of companies are based on ideological terms of sharing, connecting, and getting involved. He goes further and attacks the platforms' intentions:

Someone advancing an ideology makes a claim that does not correspond to reality and that distracts from the actual state of reality in order to hide power structures. 'Social' media companies claim they are social in order to advance the unsocial and the anti-social. (p. 53)

However, several scholars affirm its role in community building and political participation after the initial technophilia generated by the advent of the Internet and the subsequent disenchantment, as evidenced by the authors of Critical Studies 2.0. They emphasize using the Internet for entertainment, such as online games, and its contribution to democracy by providing new ways of accessing social capital. However, the heterogeneity of members sharing a virtual space and social tolerance is not limited to online games and can easily be generalized to other types of communities (Kobayashi, 2010).

For their part, Shelley Boulianne and Yannis Theocharis (2018) also agree on the potential of the Internet but condition it on the nature of its use. They stress that young people use digital media for civic purposes, such as reading the news, joining groups, and discussing political issues on social media. Moreover, the cost of mobilization is dramatically lower with the Internet, which can reinvigorate the repertoire of participation. However, pejorative terms such as clicktivism, click-activism, slacktivism, or "flash activism" have proliferated to denote a lack of commitment to participation (Treré & Cargnelutti, 2014).

The Platform of Those Affected by Mortgage

In February 2009, the Platform of Those Affected by Mortgage (PAH) was set up in Barcelona. Ada Colau and Adrià Alemany were joined by Ernest Marco, Guillem Domingo, Lucía Delgado, and Lucía Martín in the founding nucleus (Colau & Alemany, 2012). Marco and Domingo previously worked in the Ateneu Candela in Terrassa, near Barcelona. This space comprised people from the traditional squatter movement but also from spaces of solidarity with Guatemala and Nicaragua, demands for universal basic income, and free flow culture (Mir et al., 2013).

In the aforementioned center took place the Social Rights Offices, a network of different urban nodes of provincial capitals (Madrid, Seville, and Malaga, among others). It was inspired by the Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN) and alter-globalization, and also addressed issues related to the right to housing (Sebastiani et al., 2016).

Another strategic alliance was formed with neighborhood associations, which became one of the channels of expansion of the movement. They had a long history of defending the right to housing and working from proximity, embodied in the local social reality of different neighborhoods. This action was the key to decentralizing and rooting the movement in the territory. On the other hand, this alliance was welcomed by the neighborhood movement, which saw the PAH as a tool to revitalize associations in need of regeneration and reconnection with new social conflicts (Colau & Alemany, 2012).

The platform's intention to fight on two fronts was clear from the start. On the one hand, achieving the deed in lieu ofpayment means that the debt is settled with the delivery of the mortgaged property to the creditors. It happens in the legislation of the countries of the European environment. In Spain, the debt falls on the person, not the house. On the other hand, stopping the evictions without alternative housing, putting an end to the violence and lack of protection, which means leaving thousands of families on the streets, while at the same time, the financial institutions, which are primarily responsible for the current crisis, accumulate thousands of empty apartments, waiting to return to speculate with them (Colau, 2011).

The relationship between the PAH and the contemporary 15-M movement is close and cross-cutting, coming together in the ends and the means to achieve them through synergies. More so in Madrid, with those who occupied Plaza Mayor, than in Barcelona, with those who were deployed in Plaza Catalunya, the collaboration was strengthened in different areas, especially when it came to mobilizing a greater number of citizens to stop the evictions and guarantee the success of the enterprise. This was something that had previously been doubtful and marginal. On the contrary, the PAH responded well to the demands and claims of the Indignados, even if they were unrelated to the right to housing. There was a temporary and, above all, ideological convergence.

The 15-M movement was in the same orbit as Occupy Wall Street and the Arab Springs. Its development led to its decentralization and the creation of neighborhood assemblies initially convened in a single nodal point in each city. The creation of working groups and logistical commissions led to the emergence of specific groups, some linked to sectoral waves.

The housing situation has been one of the most prominent areas of protest and action since the beginning of the movement, adding collective actions to stop evictions and giving impetus to groups such as the Platform of Those Affected by Mortgages. (Lobera & Sampedro 2014, p. 465)

The Indignados created their seal of identity by identifying the actors responsible for the situation, developing a repertoire of specific slogans ("We are not a commodity in the hands of bankers and politicians," in explicit reference to the PAH), and elaborating general proposals. The activists drew on previous failed experiences in the movement for decent housing and the unsuccessful construction of mobilization frameworks that did not have the expected support. The most intense period of 15-M facilitated the recruitment of demobilized citizens into the activities and structures of organizations already working on social issues, including PAH (Romanos, 2014).

As it converged with 15-M, this explosion was also supported by the spread of open calls through social media to stop the evictions. Especially on Twitter, they were hoarded and dominated by Indignados activists. The occupation of the Plaza Mayor and the rest of the Spanish cities was accompanied by network struggles. There, they tried to break and install an alternative history, not only as a space to communicate coordination and appeal but also in the arena where the battle was fought and won.

On the other hand, the diversity and the confluence of different struggles presented the 15-M movement with the difficulty of coordinating actions and making them visible in the face of an agenda full of multiple initiatives. The calls had to break through and be coordinated among many others. For their part, the Indignados relied on the PAH's work in housing and finance to concretize their demands, including delays in payments and the postponement of evictions.

The escraches campaign, among others, was fought both on the streets and in virtual social networks. In addition to being attacked by political parties and the traditional press, it was supported by other actors such as Juventud Sin Futuro, giving the protest a transversal dimension. In any case, the demands of the 15-M converged in demands for respect for human rights, "real democracy now," and greater citizen participation in democratic practices (Flesher Fominaya, 2015).

Framing for Mobilizing

Frame theory has been widely used in the analysis of social movements because of its flexibility and adaptability to the object of study. But before that, the foundations were laid by Berger and Luckmann (1966) from a constructivist approach that describes human interactions in everyday life. From a micro-sociological perspective, Goffman (1974) developed a theory that revealed the organization of experience by applying frame analysis.

Frames can be understood as mental orientations that organize perception and interpretation. Understanding a communicative act requires reference to a metamessage about what is happening; that is, a framework of interpretation applied to that act has a dynamic, collective, and relevant character in social relations (Entman, 1993). Moreover, this meaning interaction is not entirely determined in advance but is instead a collective production. The interactive process consists not only of two utterances produced by the speaker and the listener, but also of their respective interpretations (Rivas, 1988).

In terms of definition and operability, mental frameworks are an elusive concept, difficult to separate and measure. Drawn from a variety of disciplines, frameworks are elastic and malleable, and there is no single agreement on what should be understood as a precise concept. As a methodology, it has mainly been discussed by pragmatic linguists and critical discourse analysts (Van Dijk, 2020).

However, sociological studies of communication agree that each frame has a set of characteristics that make it appropriate to consider communicative and cultural dynamics in theoretical and empirical approaches (Tàbara et al., 2004).

Starting from the premise that the effects of framing are not limited to providing meaning or a rational explanation of a given situation but also to moralizing and prescribing, Tàbara et al. (2004) identify four contemporary elements: perceptibility, rationality, morality, and prescriptiveness.

From the Anglo-Saxon liberal, pragmatic school, McAdam et al. (2008) identify three factors outside the frames as essential for collective mobilization. These are the structure of opportunities and constraints, forms of organization, and "the collective processes of interpretation, attribution, and social construction that mediate between opportunity and action." In other words, they reserve one of the three pillars for the symbolic construction of meaning at the same level as the particular situation of each specific case.

Methodology

In order to answer the research question, "How does the organization struggle to impose cognitive frameworks that value the importance of housing in the long term and at the same time manage to give a quick response to the daily mobilization around evictions?" we developed a set of frames and counter-frames based on Ramon-Pinat (2022), as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Pairs of frames and alternative frames

Frame - long term |

Counter-frame - short term |

Housing as a right |

Housing as an economic asset |

Social-collective issue |

Individual cases |

National structural intervention |

City council assistance |

PAH as a multidisciplinary movement |

PAH as an anti-eviction movement |

Source: Own elaboration.

Housing as a right: The main objective of PAH is to change the traditional concept of housing as property to the right of use and possession. The movement has promoted a legislative initiative in the Spanish Parliament to guarantee access to housing for the population.

Housing as an economic asset: The main reason for evictions is the high prices that cannot be paid. The solution to access to housing is for everyone to be able to work and earn enough money to afford it. Gentrification processes and real estate development are necessary and positive and serve to regenerate neglected areas.

Social collective issue: Access to housing does not only concern a critical minority of the population at risk of exclusion. On the contrary, it is a general situation that affects a wide range of citizens. Working and middle-class people are excluded from their homes if they cannot afford it.

Individual cases: Information is presented in isolation, out of context. They are individual cases, unusual evictions of older adults, families with children, or disabled people. These extreme situations generate sympathy, visibility, and anger, creating a sense of injustice. On the other hand, they do not provoke identification or empathy.

National structural intervention: This calls for a structural solution through public intervention—protectionist policies with effective regulation of prices and contractual conditions for mortgages and rentals. There must be a change in legislation with far-reaching measures. This includes the conditions in the legislative initiative promoted by the movement in the Spanish Parliament. Far from palliative subsidies, it is a maximum solution.

Help from the municipality: The solution involves the intervention of social services, the transfer of spaces, and the appeal to palliative charity. Municipalities must intervene to provide care and shelter to the most vulnerable citizens. A housing alternative to the eviction of minors or the elderly. It is consistent with a minimum short-term solution.

PAH as a multidisciplinary movement: It is presented as a group that works to change the roots of society, challenging the traditional view of housing as property. It also cares for affected citizens with health and other problems related to the lack of housing.

PAH as an anti-eviction movement: The platform is presented as an association that meets ad hoc to stop evictions. As an action on demand, it acts as a group of people who, with more or less violence, prevent people from being evicted.

Corpus selection

The official fan page of PAH on Facebook is called "Afectados por la Hipoteca"; its ID is 165740193488717. It began as a personal profile until June 13, 2011, when it reached 5,000 contacts and was forced to convert to a fan page format to continue gaining followers, as announced in a post on that date. In the following time, it hosted 2,287 publications on its wall, 1,026,823 reactions, 43,845 comments, and 570,357 shares. In the selected period of analysis, between October 17, 2013, and February 12, 2016, 218 entries speak of evictions in the official PAH account on Facebook, constituting the study corpus (Table 2).

Table 2. Frame analyses in Facebook and Twitter

Housing as |

Diagnosis |

Solutions |

PAH movement |

|||||||

Total posts |

A right |

An asset |

Social |

Individual |

Structure |

Assistance |

Multilayers |

Anti-eviction |

Total |

|

3,199 |

676 |

629 |

911 |

2,154 |

536 |

742 |

963 |

1,55 |

8,161 |

|

Tweet rate (100%) |

21.13 |

19.66 |

28.48 |

67.33 |

16.76 |

23.19 |

30.10 |

48.45 |

||

Frame rate (100%) |

8.28 |

7.71 |

11.16 |

26.39 |

6.57 |

9.09 |

11.80 |

18.99 |

||

218 |

113 |

64 |

116 |

94 |

80 |

44 |

77 |

82 |

670 |

|

Post rate (100%) |

51.83 |

29.36 |

53.21 |

43.12 |

36.70 |

20.18 |

35.32 |

37.61 |

||

Frame rate (100%) |

16.87 |

9.55 |

17.31 |

14.03 |

11.94 |

6.57 |

11.49 |

12.24 |

||

Source: Own elaboration.

The Netvizz application, developed by the University of Amsterdam (Rieder, 2013), was used to obtain the Facebook corpus. This application allows systematic access to the content and is designed to facilitate the task of social science researchers, given the growing interest in this field as an object of study. The advantage of Netvizz over NodeXL and other similar resources is that it does not require Microsoft Excel or a Windows operating system since it runs as a web application. The raw data obtained corresponds to personal networks and sites. Regarding privacy and anonymity, Netvizz clarifies that it does not use data other than for functionality, that it does not access any extra content, that it does not store any personal profile, and that the files generated are periodically deleted from the server (Rieder, 2013).

The Twitter material, on the other hand, was collected manually using the Export to PDF extension offered by the Safari web browser. Later, this content was transferred to a Google Sheet spreadsheet for manipulation. In order to be more comprehensive, the search query included the option "Tweets and replies," although those tweets that were only single conversations were later manually eliminated. The official PAH account on Twitter is @LA_PAH, which was opened in April 2010 and had 90,803 followers as of October 11, 2017. Twitter has a limitation regarding access to old content, so the recall was done in seven waves. In the analyzed period of two years and four months, 3,199 tweets talk about evictions, in which we could identify a total of 8,161 frames. They were all manually coded. In both cases, only the organization's posts were analyzed, not those published by followers.

Analysis

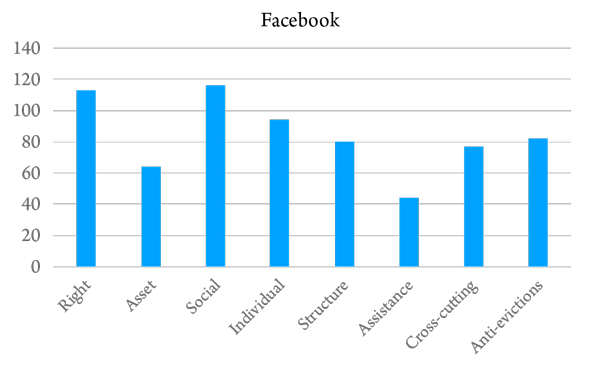

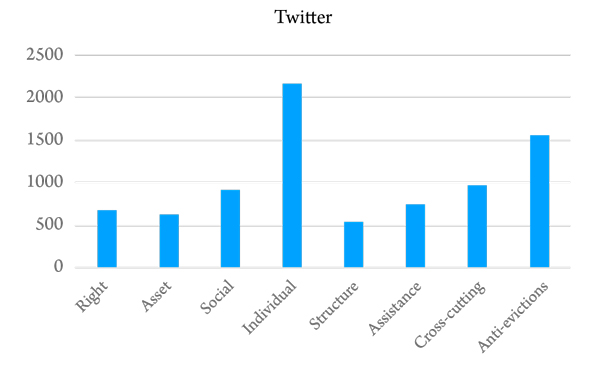

During the analyzed period, from October 17, 2013, to February 12, 2016, the official Facebook account of PAH, "Afectados por la hipoteca," published 218 posts about evictions. More than half of these posts advocate for housing as a right, while less than a third consider it a commodity. The official Twitter account of the PAH is @LA_PAH, active since April 2010 and has had 90,803 followers as of October 11, 2017. During the analyzed period of two years and four months, we identified 3,199 tweets about evictions, totaling 8,161 framings. Most of these tweets treat the conflict as a particular case, accounting for more than two-thirds of the total, while less than half provide a social diagnosis (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1. Frame analysis on Facebook.

Source: Own elaboration

Figure 2. Frame analyses on Twitter.

Source: Own elaboration.

On both Facebook and Twitter, the official accounts of the PAH prioritize housing as a right over a mercantilist vision, although with some nuances. The difference in the ratio of frames found between Twitter and Facebook is slight on Twitter but almost double on Facebook.

Regarding the conflict diagnosis, there is a divergence between the two networks. On Facebook, the platform emphasizes the social nature of the conflict, while on Twitter, it is treated as a specific case in over two-thirds of the entries. The addresses of requests also differ between the two social networks. On Facebook, almost twice as many requests for structural solutions confirm the initial proposal. On Twitter, the difference is more significant for requests for help.

However, both platforms fail to provide a comprehensive image of the nuances and areas they offer as a group, including support and containment activities that extend beyond the housing field. However, Twitter exacerbates this situation due to the immediacy of responses, particularly in critical communications regarding the urgency of resolving imminent evictions. Despite their significance, framings only account for a quarter of the total counted.

Conclusions

This research aims to analyze how the PAH strives to establish enduring cognitive frameworks that prioritize the right to housing while also providing prompt responses to daily mobilizations related to evictions in the short term. On Twitter, approximately one in five individuals discuss this issue due to its relevance to daily activism. On Facebook, over half of the users engage in asynchronous communication, resulting in less urgency. The frequent mention of housing as a commodity is likely due to the organization's desire to bring attention to the names and surnames of the entities responsible for evictions. This can lead to treating housing as a mere object for purchase and sale for economic reasons.

The use of Twitter for daily mobilization to stop evictions often highlights only the most extreme cases, making it difficult to identify with the majority of citizens. This implies that the housing problem is only prevalent in extreme cases and not in the majority of society. The organization's real-time mobilization of activists to stop evictions was highlighted for its speed. However, the speech called for urgent solutions to provide shelter for evicted families rather than making far-reaching demands for a new mortgage law to address the root causes of the housing crisis in the state. In these cases, their use is also acceptable, but it hinders the development of long-term solutions beyond immediate needs.

The same approach is applied to new social media activism as in the analogical age. The Anglo-Saxon school focuses on a pragmatic-strategic point of view, while the continental European school analyzes cultural identities and intangibles. The activists of PAH speak of identity as their primary asset, of the sense of belonging that unites them. At first, realizing they were not alone in facing this massive problem was crucial. Facebook is a vital tool for affected individuals to make initial contact through instant messaging. Subsequently, Twitter has become increasingly important for engaging with other actors, including political parties and the wider society. However, the interference of algorithms has resulted in the development of "filter bubbles" and "echo chambers," which, on the one hand, strengthen the bonds between sympathizers, creating a sense of community and shared identity. However, to the difficulty in reaching and recruiting new members hinders expansion.

In media academics, there is often an overestimation of the role of communication. In PAH, communication is secondary to face-to-face contact, weekly meetings, and street actions, which take precedence. Social media merely reflect the sense of community and shared values. The posts focus on publishing pictures that feature a group of people wearing green t-shirts to represent the movement rather than highlighting a single main character. Additionally, they consistently end with an optimistic message of hope, which serves as an invitation to those suffering.

Regarding public interaction, after the Indignados 15M movement, there was a period of increased bot and troll activity, as well as the use of black-box algorithms. Additionally, Twitter's acquisition by Elon Musk and its rebranding as "X" marked a new era where social media neutrality is no longer guaranteed. Hie content manager for the organization is aware that once they post something, there will likely be much negative feedback from haters and trolls. In response to this situation, Facebook has emerged as an alternative. He message may be more impactful with a smaller audience.

As the phrase "on Twitter you say what you do, while on Facebook you say who you are" suggests, Twitter implies a frenetic and constant pragmatism, while Facebook is intended to build an identity beyond the content disclosed. In both cases, promoting a particular position and generating empathy is facilitated (the "identity" frame). Regarding internal coordination, Telegram plays a crucial role, although it is beyond the scope of this research.

He primary cause of eviction during this research was non-payment of mortgages. However, currently, most evictions occur due to rent increases. His leads to a more transient movement, making it more challenging to establish identity links among those affected. In previous cases, the judicial process could take up to a year, allowing people to meet and assist in resolving other cases. Nowadays, due to high member turnover, it often takes just one or two months for team members to change, making it difficult for them to get to know each other.

References

Bennett, W. L. (2012). He personalization of politics: Political identity, social media, and changing patterns of participation. The annals of the American academy of political and social science, 644(1), 20-39. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716212451428

Berger, P., & Luckmann, T. (1966). The social construction of reality: A treatise in the sociology of knowledge. Anchor books.

Boulianne, S. & Heocharis, Y. (2018). Young people, digital media, and engagement: A meta-analysis of research. Social Science Computer Review, 38(2) 111-127. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439318814190

Chadwick, A. (2007). Digital network repertoires and organizational hybridity. Political Communication, 24(3), 283-301. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584600701471666

Colau, A. (2011). Como se para un desahucio. Plataforma de Afectado por la Hipoteca. https://afectadosporlahipoteca.files.wordpress.com/2011/07/como-parar-desahucio_a-colau1.pdf

Colau, A., & Alemany, A. (2012). Mortgaged Lives: From the housing bubble to the right to housing. Journal of Aesthetics & Protest Press.

Crone, V., & Post, J. (2015). Reporting Revolution. Digital Journalism, 3(6), 871-887. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2014.990253

Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication, 43(4), 51-58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x

Flesher Fominaya, C. (2015). Redefining the crisis/redefining democracy: mobilising for the right to housing in Spain's PAH movement. South European Society and Politics, 20(4), 465-485. https://doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2015.1058216

Fuchs, C. (2011). Foundations of critical media and information studies. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203830864

Fuchs, C. (2018a). Digital demagogue: Authoritarian capitalism in the age of Trump and Twitter. Pluto Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt21215dw

Fuchs, C. (2018b). Socialising Antisocial Social Media. In J. Mair, T. Clark, N. Fowler, R. Snoddy, & R. Tait (Eds.), Antisocial Media: The Impact on Journalism and Society (pp. 58-63). Abramis Academic Publishing.

Fuchs, C., Hofkirchner, W., Schafranek, M., Raffl, C., Sandoval, M., & Bichler, R. (2010). Heoretical foundations of the web: Cognition, communication, and cooperation. Towards an understanding of Web 1.0, 2.0, 3.0. Future Internet, 2(1), 41-59. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi2010041

Gerbaudo, P. (2017). The mask and the flag: Populism, citizenism and global protest. Oxford University Press.

Gerbaudo, P. (2019a). Del ciber-autonomismo al ciber-populismo: Una historia de la ideología del activismo digital. Defensa del Software Libre.

Gerbaudo, P. (2019b). The digital party: Political organisation and online democracy. Pluto Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv86dg2g

Gerbaudo, P. & Treré, E. (2015). In search of the 'we' of social media activism: Introduction to the special issue on social media and protest identities. Information, Communication & Society, 18(8), 865-871. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2015.1043319

Goffman, E. (1974). Frame analysis: An essay on the organization of experience. Harvard University Press.

Hardt, M., & Negri, T. (2018). He Multiplicities within Capitalist Rule and the Articulation of Struggles. TripleC: Communication, Capitalism & Critique, 16(2), 440-448. https://doi.org/10.31269/triplec.v16i2.1025

Howard, P. (2010). The Digital Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy: Information Technology and Political Islam. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199736416.001.0001

Kaun, A., & UldamJ. (2018). Digital activism: Afterthe hype. NewMedia & Society, 20(6), 2099-2106. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444817731924

Kim, S., & Weaver, D. (2002). Communication research about the Internet: A thematic meta-analysis. New media & society, 4(4), 518538. https://doi.org/10.1177/146144402321466796

Kittur, A., Chi, E., Pendleton, B., Suh, B., & Mytkowicz, T. (2007). Power of the few vs. wisdom of the crowd: Wikipedia and the rise of the bourgeoisie. World Wide Web, 1(2), 19.

Kobayashi, T. (2010). Bridging social capital in online communities: Heterogeneity and social tolerance of online game players in Japan. Human Communication Research, 36(4), 546-569. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2010.01388.x

Lobera, J., & Sampedro, V. (2014). La transversalidad del 15M entre la ciudadanía. In E. Serrano, A. Calleja-López, A. Monterde, & J. Toret (Eds.), 15MP2P. Una mirada transdisciplinar del 15M (pp. 470-489). UOC-IN3.

Lovink, G. (2004). Fibra Oscura: Rastreando la cultura crítica de Internet. Tecnos/Alianza.

Lovink, G. (2016). Redes sin causa: una crítica a las redes sociales. Editorial UOC.

Machado, J. (2007). Ativismo em rede e conexões identitárias: novas perspectivas para os movimentos sociais. Sociologias, (18), 248-285. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1517-45222007000200012

McAdam, D., McCarthy, J., & Zald, M. (2008). Comparative perspectives on social movements: Political opportunities, mobilizing structures, and cultural framings. Cambridge University.

Mir, J., França, J., Macias, C., & Veciana, P. (2013). Fundamentos de la Plataforma de Afectados por la Hipoteca: activismo, asesoramiento colectivo y desobediencia civil no violenta. Educación Social: Revista de Intervención Socioeducativa, 55, 52-61.

Quijada, C. (2014). Estudiantes conectados y movilizados: El uso de Facebook en las protestas estudiantiles en Chile. Comunicar: Revista científica iberoamericana de comunicación y educación, 43(22), 25-33. https://doi.org/10.3916/C43-2014-02

Quintana, Y., & Tascón, M. (2012). Ciberactivismo: Las nuevas revoluciones de las multitudes conectadas. Los Libros de la Catarata.

Ramon-Pinat, E. (2022). The difficulties in spreading housing rights discourse in the face of 'right now' pragmatism on Twitter. Communication & Society, 35(2), 299-311. https://doi.org/10.15581/003.35.2.299-311

Rieder, B. (2013). Studying Facebook via data extraction: He Netvizz application. In Proceedings of the 5th annual ACM web science conference (pp. 346-355). https://doi.org/10.1145/2464464.2464475

Rivas, A. (1988). El análisis de marcos: una metodología para el estudio de los movimientos sociales. In P. Ibarra & B. Tejerina (Eds.), Los movimientos sociales. Transformaciones políticas y cambio cultural. Editorial Trotta.

Romanos, E. (2014). Evictions, petitions and escraches: Contentious housing in austerity Spain. Social Movement Studies, 13(2), 296-302. https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2013.830567

Sebastiani, L., Fernández, B., & García, R. (2016). Lotte per il diritto alla casa nello Stato spagnolo: la Plataforma de Afectados por la Hipoteca. Campagne, successi e alcune chiavi di riflessione. Interface: a journal for and about social movements, 8(2), 363-393.

Tàbara, J., Costejà i Florensa, M., & Van Woerden, F. (2004). Las culturas del agua en la prensa española. Los 'marcos culturales' en la comunicación sobre el Plan Hidrológico Nacional. Papers: Revista de sociologia, (73), 153-179. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/papers/v73n0.1112

Treré, E. (2019). Hybrid media activism: Ecologies, imaginaries, algorithms. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315438177

Treré, E., & Cargnelutti, D. (2014). Movimientos sociales, redes sociales y Web 2.0: El caso del Movimiento por la Paz con Justicia y Dignidad. Comunicación y Sociedad, 27(1), 183-203. https://doi.org/10.15581/003.27.36010

Tufekci, Z. (2014). Engineering the public: Big data, surveillance and computational politics. First Monday, 19(7). https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v19i7.4901

Van Dijk, T. A. (2020). Critical review of framing studies in social movement research [unpublished]. Centre of Discourse Studies.

Walgrave, S., Bennett, W. L., Van Laer, J., & Breunig, C. (2011). Multiple engagements and network bridging in contentious politics: Digital media use of protest participants. Mobilization: An International Quarterly, 16(3), 325-349. https://doi.org/10.17813/maiq.16.3.b0780274322458wk