|

Artículo

Benson Rajan1

Lydia G. Jose2

Thejas Sundar3

1 ![]() 0000-0003-3340-8726. O.P. Jindal Global University, India. brajan@jgu.edu.in

0000-0003-3340-8726. O.P. Jindal Global University, India. brajan@jgu.edu.in

2 ![]()

![]() 0000-0003-3296-9169. IILM University, India. lydia.jose@iilm.edu

0000-0003-3296-9169. IILM University, India. lydia.jose@iilm.edu

3 ![]() 0000-0001-5409-5250. Institute for Social and Economic Change, India. thejas@isec.ac.in

0000-0001-5409-5250. Institute for Social and Economic Change, India. thejas@isec.ac.in

Recibido: 09/07/2021

Enviado a pares: 09/08/2021

Aprobado por pares: 08/11/2021

Aceptado: 17/12/2021

Para citar este artículo / to reference this article / para citar este artigo: Rajan, B., Jose, L. G., & Sundar, T. (2022). Are You Hooked to the ‘Gram’? Exploring the Correlation between Loneliness, the Fear of Missing Out, and Instagram Usage among Young Indians. Palabra Clave, 25(2), e2525. https://doi.org/10.5294/pacla.2022.25.2.5

Abstract

The amount of time spent on Instagram by young people in India has grown exponentially. This social media platform is a sea of visuals that reflect the activities people are engaging in. The constant viewing of other people’s lives can lead to a feeling of dissatisfaction about one’s own life. The Fear of Missing Out (FoMO) emerges when an individual who is unable to participate in or engage with the activities of others, experiences feelings of loneliness and isolation. This study aims to examine the association between the time spent on Instagram and its effect on FoMO and Loneliness. The study sample consisted of 401 participants, primarily 18–24 years old, collected via convenience sampling methods. The single item Fear of Missing Out short form (FoMOsf) and the three-item Loneliness scale were administered to participants to measure FoMO and loneliness, respectively. Descriptive and inferential statistics were used to analyze the data. A one-way analysis of variance was computed between the time one spends on Instagram and the variables of FoMO and loneliness. The analysis uncovered a statistically significant difference between the increasing amount of time spent on Instagram, that is, less than one hour, 1–2 hours, and three or more hours for FoMO [F (2,398) = 17.92, p < 0.05] and loneliness [F (2,398) = 3.57, p ≤ 0.029]. Therefore, more time spent on Instagram results in individuals experiencing significantly greater levels of FoMO and loneliness.

Keywords (Source Unesco Thesaurus): Instagram; social media; India; young people; loneliness; fear of missing out; FoMO.

Resumen

La cantidad de tiempo que los jóvenes de la India pasan en Instagram ha crecido de manera exponencial. Esta plataforma de redes sociales es un mar de imágenes que reflejan las actividades que realizan las personas, pero la visualización constante de la vida de otras personas puede generar un sentimiento de insatisfacción con respecto a la propia vida. El miedo a perderse de algo (FoMO, por sus siglas en inglés) surge cuando una persona que no puede participar o comprometerse con las actividades de los demás experimenta sentimientos de soledad y aislamiento. El presente estudio tiene como objetivo examinar la asociación entre el tiempo dedicado a Instagram y su efecto en el FoMO y la soledad. La muestra del estudio consta de 401 participantes, principalmente entre los 18 y 24 años de edad, involucrados mediante métodos de muestreo por conveniencia. Se aplicó a los participantes el formulario abreviado del FoMO de un solo ítem (FoMOsf) y la escala de soledad de tres ítems para medir el FoMO y la soledad, respectivamente. Se utilizó estadística descriptiva e inferencial para analizar los datos y se realizó un análisis de varianza de una vía entre el tiempo que uno pasa en Instagram y las variables FoMO y soledad. En el análisis, se descubrió una diferencia estadísticamente significativa entre el aumento de la cantidad de tiempo dedicado a Instagram, es decir, menos de una hora, 1 a 2 horas y tres o más horas para el FoMO [F (2398) = 17,92, p < 0,05] y la soledad [F (2.398) = 3,57, p ≤ 0,029]. Por lo tanto, pasar más tiempo en Instagram hace que las personas experimenten niveles significativamente mayores de FoMO y soledad.

Palabras clave (Fuente Tesauro de la Unesco): Instagram; redes sociales; India; jóvenes; soledad; miedo de perderse de algo.

Resumo

A quantidade de tempo que os jovens da Índia passam no Instagram vem crescendo de maneira exponencial. Essa plataforma de redes sociais é um mar de imagens que refletem as atividades que as pessoas realizam, mas a visualização constante da vida de outras pessoas pode gerar um sentimento de insatisfação a respeito da própria vida. O medo de ficar de fora (FoMO, por sua sigla em inglês) surge quando uma pessoa que não pode participar ou se comprometer com as atividades dos demais experimenta sentimentos de solidão e isolamento. Este estudo tem o objetivo de analisar a associação entre o tempo dedicado ao Instagram e seu efeito no FoMO e na solidão. A amostra do estudo consta de 401 participantes, principalmente entre 18 e 24 anos de idade, envolvidos mediante métodos de amostragem de conveniência. Foi aplicado aos participantes o questionário abreviado do medo de ficar de fora de um só item (FoMOsf) e o inventário de solidão de três itens para avaliar o FoMO e a solidão, respectivamente. Foi utilizada estatística descritiva e inferencial para analisar os dados e foi realizada uma análise de variância de uma via entre o tempo gasto no Instagram e as variáveis FoMO e solidão. Na análise, foi constatada uma diferença estatisticamente significativa no aumento da quantidade de tempo dedicado ao Instagram, isto é, menos de uma hora, de 1 a 2 horas e 3 horas ou mais para o FoMO [F (2398) = 17,92, p < 0,05] e a solidão [F (2.398) = 3,57, p ≤ 0,029]. Portanto, passar mais tempo no Instagram faz com que as pessoas experimentem níveis significativamente maiores de FoMO e de solidão.

Palavras-chave (Fonte tesauro da Unesco): Instagram; redes sociais; Índia; jovens; solidão; medo de estar perdendo algo.

Introduction

Instagram has become one of the most popular social networking sites for young people, and India has ranked first for the greatest number of users with a growth of 16.7 per cent after the United States, with both the countries having 140 million users (Clement, 2020; Hootsuite, 2021). It is easily accessible on smartphones as an application, enabling an exchange of user-generated content (Kohler et al., 2020). It helps young people stay in touch with each other, post news about themselves, and follow others who share their interests. It builds a community of like-minded individuals who share the highlights of their life using this platform. This decade has seen Instagram become one of the most prominent socializing spaces, and the amount of time spent on Instagram by young people has consistently increased over time, in contrast to other social networking sites such as Facebook (eMarketer Editors, 2019).

Social networking sites enable people to create profiles for themselves through which they are exposed to a vast display of information about others’ lives (Fardouly et al., 2015). Instagram is such a social media site that allows sharing photos and videos of oneself and one’s various interests, leading to social comparison among users (Yang et al., 2018). Studies have shown that young people spend more time on Instagram than on Facebook (Salomon, 2013). One of the reasons that studies cite is the psychological drive that motivates youngsters to take pictures and share them on the app almost instantaneously (Abbott et al., 2013). Users also keep their profiles public on Instagram, enabling anyone, including famous influencers and celebrities, to like or comment on a picture that one posts. The hashtags on each post allows for effortless searches and provides more visibility to a larger crowd than the existing friend circle that a user may follow (Lup et al., 2015). Studies have shown that extreme usage of Facebook predicts social/emotional loneliness (Wang et al., 2018). However, limited studies have been conducted on the picturesque enriched social media Instagram and its relation with loneliness and fear of missing out.

The Instagram experience is visually dominant, providing cues that an audience can interpret and consume. These visuals enable people to make educated guesses about people’s social status, education, income, family background, and relationships, among other things (Reiss & Tsvetkova, 2019). Part of these guesses is a focus on the self, which involves the opportunity of engaging in any activity at the cost of missing out on others. This is the concept of fear of missing out (FoMO). It refers to the “pervasive apprehension that others might be having rewarding experiences from which one is absent” (Przybylski et al., 2013). The concept of FoMO arises in a person when the psychological deficiency for competence and relational needs occurs within themselves. One way people try to fulfil this need is by using social networking sites where they can have a consistent and constant flow of social and informational rewards (Deci & Ryan, 1985).

With social media, people constantly feel compelled to check their Instagram account to ensure that their current experience is not inferior to other experiences they could be having elsewhere. So, the lack of access to Instagram information leads to FoMO (Hampus & Lood Thelandersson, 2020). Viewing others’ lives on Instagram highlights the gaps in one’s own experiences, thus creating the fear of an unlived life.

The use of social media has been compared to cocaine addiction, but not as intense. Trevor Haynes (2018) explained how people’s brains release a pleasure-giving chemical known as dopamine when using social media platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat. The 60-minute interview (Cooper, 2017) explained how Instagram’s notification algorithms withheld “likes” on pictures at times, to deliver them in larger bursts. Consequently, a person might be able to see only fewer responses to one’s post but later will receive a larger number of likes. This algorithm, according to Haynes, lets the dopamine centres in one’s brain be influenced by the initial negative response, so that they have a dopamine release when they see a sudden influx of social approval from their posts later (Haynes, 2018). Such influx of larger bursts of appreciation leads a person to keep coming back to the app, and the lack of it can create a sense of FoMO within oneself. Therefore, this study aims to examine the association between time spent on the social media app Instagram and whether it results in FoMO and Loneliness in the youngsters in India. The study is conducted using the convenience sampling method with 401 participants aged 18-24 years.

Literature review

Many studies have been conducted on social media’s effects on consumers’ loneliness and self-representation. However, these studies show contradictory findings, and their conclusions are subject to many conditions posed by the research itself. Some research papers suggest a positive impact on loneliness, anxiety, depression with the usage of social networking sites (Nowland et al., 2017; Pittman & Reich, 2016; Song et al., 2014), while some others say that there is a pervasive influence on social or emotional loneliness and self-representation in individuals (Blachnio et al., 2016; Dibb & Foster, 2021; Hunt et al., 2018; Riehm et al., 2019).

Users on social media generally display themselves selectively and build an identity or depict characteristics that they prefer to portray to their friends (Vogel et al., 2014). Positive appraisals available on social media platforms, such as comments, likes, and others, build an involuntary tendency within users’ minds to compare their lives with that of users who have more followers. Comparing information present on social media is ubiquitous and generally performed by most users (Appel et al., 2016). Likewise, the lack of appraisal on social media makes users feel lonely and less appreciated. The kind of message conveyed on social media itself can be considered a key component for a user’s source of low self-esteem. Viewing other posts that convey happiness and better lives makes users compare their lives with the one portrayed on social media, causing them to believe theirs are less satisfactory (Stapleton et al., 2017).

There have been studies on screen time and its positive correlation to depression (Twenge et al., 2017). However, research on Instagram usage is limited and primarily focuses on women and body image concerns (Rajan, 2018). Most of the studies on social networking sites have explored the role of social comparison and peer envy in depression (Tandoc et al., 2015). An experimental study found that if social media usage on the phone were limited to 10 minutes per day for three weeks consecutively, social well-being would improve. Depression and loneliness were assessed in the experimental group, revealing a steady decline when the time spent on social networking sites was properly managed (Hunt et al., 2018). It has also been found that many social media users are not conscious about the amount of time they spend on social networking sites (Hunt et al., 2018). In Riehm et al.’s (2019) study that involved 6,595 adolescents, they observed that the more time individuals spent on social media, the more they were prone to experience cyberbullying, idealized self-presentation, and poor emotion regulation that could be associated with repeat, anxiety and depression. Another study showed that individuals aged 18-24 spent more time on Instagram; around 64 per cent of college students spent more than 30 minutes daily, and 20 per cent more than 90 minutes daily on the video and picture sharing app. The study also revealed that women had higher response rates than men, as they had more followers and followed more accounts on Instagram (Moore & Craciun, 2020). Therefore, the time spent on social media is a reading exercise on other people’s lives, which can create FoMO about the, life, not being lived, the, life, being missed out on, the, life, one could be leading but for some reason is not.

Social networking sites are viewed as an no needed extension of the self (Clayton et al., 2015; Kruger & Djerf, 2016). This perceived self includes other people, personal possessions, and groups that one may relate to the personal body and mind (Belk, 1988). Maintaining physical and digital groups to which one may feel attached is considered crucial in modern society. When one cannot be in touch with these virtual groups that include physical possessions or other people digitally, a sense of dissatisfaction comes from within—as if one is out of touch with “real” life (Clayton et al., 2015). It brings about emotions of grief and loss as if one has lost or does miss someone in real life, which, in turn, wounds the ‘self’ (Belk, 1988). This sense of loss or missing out on something virtually makes an individual go through FoMO (Abel et al., 2016). Therefore, when people cannot access their social media accounts, they feel as if they are being socially excluded from a group, which evokes a fear that they are being ostracized (Abel et al., 2016; Rozgonjuk et al., 2020).

A study to understand the relationship between loneliness and Facebook usage conducted on 550 participants determined that loneliness can be one of the reasons for Facebook usage apart from self-presentation style and the need for privacy (Blachnio et al., 2016). In another study conducted in the US, individuals aged 19-32 with higher social media use were found to experience higher social isolation than the others (Primack et al., 2017). It was found that the time spent on social media led the individuals to replace genuine social interactions, which could reduce social isolation. It also concluded that the features of the digital community may evoke feelings of loneliness in individuals and that social media feeds are full of misrepresented realities than the actual lives lived (Madden et al., 2013). Hence, when individuals are exposed to such information, feelings of loneliness, unfavourable social comparison, and jealousy may emerge in their life (Tandoc et al., 2015). People who have higher anxiety of missing out were reported to use Instagram more than the others, but the number of posts on the individual’s account did not increase, whereas those with a higher tendency to FoMO were seen following more Instagram handles than the others (Moore & Craciun, 2020).

The life that an individual does not live creates a window to fantasize about what is missing, such as experiences, desires for social relationships, and the people absent in this fantasy, making one think and get emotional about one’s actual social relationships. This difference between one’s longing for social relationships and the actual relationship is a fertile ground for promoting loneliness. Studies have shown that social media spaces provide a substitute for human interactions with digital communication, leaving people with a void of intimacy and face-to-face interactions and thus creating a feeling of loneliness (Turkle, 2012). The displacement hypothesis in a study that concentrated on loneliness and social internet use (Nowland et al., 2017) suggested that social networking sites increase loneliness in individuals, as it replaces the time spent with others in real life (Kraut et al., 1998; Nie, 2001; Nie et al., 2002). This study showed that those who experience loneliness more than others displace their offline friends with those present in the digital space as they point out the number of friends presents online is higher than the number of friends offline. It was also pointed that it was easier to make companions in a virtual space than in an actual space with individuals. (Morahan-Martin & Schumacher, 2000; Sheldon & Bryant, 2016).

The time spent on social media makes one aware of what they long for in their lives and what is missing, a study on the use of Facebook (FB) in Jammu found that people use FB to overcome feelings of loneliness (Mahajan, 2013). Here, users network with people online, and their behaviour is categorized as extraversion (Ryan & Xenos, 2011). On the other hand, research provides evidence that high connectivity online is also making people lonelier (Lutz & Schneider, 2020). Loneliness can be understood as the feeling of isolation and deprivation concerning others, which emerges from the deficiencies one finds in one’s interpersonal network (Perlman & Peplau, 1981; Weiss, 1973).

Many studies have explored the association between loneliness and technology even before the advent of social media platforms. Before social networking sites, Kraut et al. (1998) had studied the relationship between individuals and their time spent on the Internet, finding out that the higher the time spent, the lonelier the person would be. In a study done by Yang (2016), interactive and passive browsing on Instagram resulted in lower loneliness whereas noninteractive activities (especially Instagram broadcasting) led to higher loneliness in individuals. It was also found that people who were less inclined to social comparison were less lonely than those otherwise (Yang, 2016). According to Catalina Toma in Slate (Winter, 2013), one spends so much time creating flattering, idealized images of oneself after browsing for that unique and perfect picture among many, without realizing that all the others are in the same race wanting to finish first looking unique and better. “The more distorted your perception is that their lives are happier and more meaningful than yours” (Winter, 2013). Since Instagram is more image-based than Facebook, it constructs a more apparent reality-distortion field.

In a study conducted by Lup et al. (2015), those users who spent more time on Instagram were associated with acute depressive symptoms and more negative social comparison with other users on the social media app. It was also observed that the more one follows strangers on Instagram, the greater the unfavourable social comparison with oneself, bringing about negative feelings (Lup et al., 2015). In another study conducted by Reece and Danforth (2017) using machine learning tools, depression could be observed in the Instagram user’s behaviour, detecting depressive signals in the posts published on the social media platform (Reece & Danforth, 2017). Another research found that since Instagram is a visually centred platform, it enables people to construct their reality through pictures and videos according to their likes and dislikes, not necessarily matching the reality they live in. Such strategic self-presentation can garner the attention of the youngsters with high levels of depressed mood, which can be seen as a form of encouragement to present a perceived reality and not their actual lives (Frison & Eggermont, 2017).

In this study, the reference to loneliness is not equivalent to physical isolation but rather an individual’s perception of being alone. This problem emerges most palpably when the path not taken by the individual is brought to the forefront, and it is distinctly different from their fixed vantage point of the present. Such feelings are getting magnified due to social media technology in our everyday lives. The constant access and endless scrolling appear to induce epidemic levels of loneliness (Mahoney et al., 2019). In Blachnio et al.’s (2016) study, loneliness was a predictor of posting more information on social media, and most of the time, it was the young individuals who were susceptible to this form of behaviour. The study also found that mobile internet users revealed more private information on social networking sites than those who accessed the platforms through web browsers (Blachnio et al., 2016).

There is a research gap where studies on social networking sites do not incorporate the Instagram experience of Indian users to understand how young people navigate their potential compared to the curated virtual world. India stands number one in reach rankings, with the most prominent advertising audiences on Instagram amounting to 140 million users (HootSuite, 2021). Therefore, this study looks at young people’s Instagram experience in India and how it relates to loneliness and FoMO. Keeping this in mind, the objectives of this study are:

1. To understand the proportion of time young people spend on Instagram.

2. To understand the relationship between the time spent on Instagram and its impact on FoMO and loneliness in young people.

Most studies on social media have looked at the impact on anxiety and depression in young people, which must be addressed as a public health concern. The novelty of the variables FoMO and loneliness brings about some specificity. FoMO and loneliness are strongly correlated to anxiety and depression, respectively. Therefore, through this study, mental health professionals working with young people may address the overarching concern of anxiety or depression, with increased insight and nuanced comprehension of their needs.

This study uses the following hypotheses to attain the study’s objectives:

· H0: Time spent on Instagram has no negative impact on FoMO and loneliness.

· H1: Time spent on Instagram has a negative impact on FoMO and loneliness.

Materials and methods

A quantitative descriptive survey method was used for data collection. The survey sample consisted of 401 participants with Instagram accounts across India (between 18 and 40 years old). The sample was collected via convenience sampling methods using Google Forms, selecting participants based on whether they were Instagram users. Permission for the study was granted by the institutional review board of Christ (Deemed to be University), Bengaluru, and informed consent was obtained from the participants before proceeding with the survey questionnaire. This study aims to understand whether the time spent daily on Instagram (one hour, 1–2 hours, and three hours or more) impacts variables such as FoMO and loneliness.

The instruments used to measure the variables were the following: (a) a single-item Fear of Missing Out Scale short form (FoMOsf) (Riordan et al., 2018), which is a one-item, five-point Likert scale (where the scores ranged from 1 = never to 5 = always); (b) the FoMOsf was developed based on the 10-item FoMO scale by Przybylski et al. (2013). There was a strong correlation between FoMOsf and FoMO scale at r = .807 (p < .001), and the test reported good test-retest reliability (Riordan et al., 2018); (c) the Three-Item Loneliness Scale (Hughes et al., 2004), which is a three-item, three-point Likert scale (where the scores ranged from hardly ever = 1 to some of the time = 2 and often = 3). All items were positively framed, and the minimum and maximum scores obtainable were 3 and 9, respectively. The scale was developed by selecting items from the Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale (R-UCLA) by Russell et al. (1980). The correlation between the R-UCLA and the Three-Item Loneliness Scale is high (at r = .82; p < .001). The alpha coefficient of reliability is 0.72 for the Three Item Loneliness Scale (Hughes et al., 2004). Data were analysed using descriptive and inferential statistics. An Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was computed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) to assess if there was a significant difference between the variables chosen (FoMO and loneliness) and the time spent on Instagram.

Results

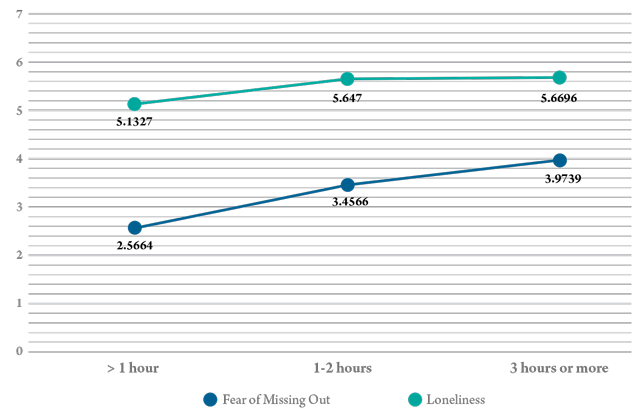

Among the 401 participants, 59.6 % (n = 239) were females, 39.15 % (n = 157) males, and the remaining 1.2 % transgender (n = 1), other (n = 1), and did not wish to specify (n = 3). Most of the population belonged to the age group between 18 and 24 years, that is, 82.3 % (n = 329), followed by 25–30 years, with 13 % (n = 52); 31–35 years, with 3.5 % (n = 14); and 35–40 years, with 1.3 % (n = 5). The time spent on Instagram in a day by most participants was 1–2 hours, with 43.3 % (n = 173); less than one hour was spent by 28 % (n = 112); and more than three hours were spent by 28.8 % (n = 115). Table 1 and Figure 1 show the descriptive analysis of the sample’s mean and standard deviation for FoMO and loneliness.

Table 1. Distribution of Data and Descriptive Statistics for Fear of Missing Out and Loneliness Concerning Time Spent on Instagram

Fear of Missing Out |

Loneliness |

|||||

Descriptive Data |

(n = 401) |

(n = 401) |

||||

>1 hour |

1–2 hours |

3 hours or more |

>1 hour |

1–2 hours |

3 hours or more |

|

N |

113 |

173 |

115 |

113 |

173 |

115 |

Mean |

25.664 |

34.566 |

39.739 |

51.327 |

5.647 |

56.696 |

Standard Deviation |

16.250 |

18.535 |

1.88 |

16.502 |

17.776 |

18.577 |

Source: Own elaboration of survey data analysed through SPSS

Figure 1. Data for FoMO and loneliness as analysed by the author(s) from the descriptive table.

Source: Own elaboration of survey data collected

A one-way between-groups analysis of variance was conducted to explore the impact of time spent on Instagram on factors such as FoMO and Loneliness. Participants were divided into three groups according to the time spent on Instagram daily (less than 1 hour, 1–2 hours, and more than 3 hours). Table 2 shows a statistically significant difference at the p < 0.05 level for FoMO across the three-time distributions (F (2,398) = 17.92, p < 0.05). A statistically significant difference was also computed at p < 0.05 level for loneliness across the three-time distributions (where F (2,398) = 3.57, p ≤ 0.029).

Table 2. One-Way Analysis of Variance for FoMO and Loneliness by Time Spent on Instagram (i.e., Less than One Hour, Two to Three Hours, and Three Hours or More)

Variable |

df |

Sum of Squares |

F |

p |

Effect Size |

Fear of Missing Out |

2 |

116.12 |

17.92 |

0.05 |

0.083 |

Loneliness |

2 |

22.28 |

3.57 |

0.029 |

0.012 |

Source: Own elaboration of survey data analysed through SPSS

Despite reaching statistical significance, the actual difference in mean scores between groups was relatively small for both loneliness and FoMO. The effect size, calculated using eta squared, was 0.083 for FoMO and 0.018 for loneliness. Post-hoc comparisons using the Tukey HSD test for FoMO indicated that the mean score for time spent on Instagram, that is, less than one hour (M = 2.55, SD = 1.63), was significantly different from the time spent on Instagram for 1–2 hours (M = 3.46, SD =1.85), and three or more hours (M = 3.97, SD = 1.88). There was also a statistically significant difference in mean scores between the time spent on Instagram for 1–2 hours and three or more hours. These results suggest that the time you spend on Instagram affects the degree of FoMO you experience. Specifically, our results suggest that when three or more hours are spent on Instagram, users experience a significantly higher degree of FoMO when compared to spending 2–3 hours or less than one hour. Besides, if one spends 2–3 hours on Instagram, it generates a significantly higher degree of FoMO than spending less than one hour.

The post-hoc comparisons using the Tukey HSD test for Loneliness indicated that the mean score for spending less than one hour on Instagram (M = 5.13, SD = 1.65) was significantly different from 2–3 hours (M = 5.65, SD = 1.77). No statistically significant difference was observed in the mean scores obtained for spending between less than one hour and three hours or more on Instagram daily; or between 1–2 hours and three hours or more. This suggests that the more time you spend on Instagram daily the more loneliness you experience; that is, when 1–2 hours are spent on Instagram in a day, more loneliness is experienced as compared to spending less than one hour a day on Instagram. Therefore, the study rejects the null hypothesis and accepts the alternate hypothesis that the time spent on Instagram negatively affects FoMO and loneliness.

Discussion

Social media has woven its way into the very fabric of modern-day interpersonal interactions. It has grown into a popular force, bearing the good intentions of connectivity with the world, and thus bridging gaps and bringing people closer. Studies on platforms such as Facebook has shown negative users’ experience when interacting with the platform (Vogel et al., 2014). Instagram presents itself as a visual application primarily with a simpler interface and design. However, through this paper, we can see how the intended positive influences of Instagram begin to dissipate as the amount of time one spends engaging with it increases.

The results of this study portrayed a significant difference between FoMO and loneliness and the time one spends on Instagram daily. It was further established that the more time one spends on Instagram daily, the more one experiences FoMO and loneliness. FoMO is no longer limited to physical absence. With Instagram and increasing smartphone usage drawing on the idea of constantly being in touch, FoMO is potentially a constant reality. It has the potential to generate a sense of exclusion, which can take on an elevated competitive behaviour (Hughes et al., 2004). FoMO contributes to a hierarchical view of self and others; it carries a fear of rejection when their activities as showcased on Instagram can be perceived as inferior to their audience. Within this hierarchical perspective, loneliness is a key ingredient. Users may feel alone as they might think that they are the only ones who are “inferior” or “not as good as others.” With an increasing amount of time being spent on Instagram, it can appear that their lived reality is not as ideal as portrayed in the content they are viewing.

From this data, it can be gathered that the time one spends on Instagram daily can be used as an indicator to help people check if their mental health is suffering from any consequences. Although FoMO and loneliness are not direct measures to assess deteriorating mental health concerns, they can be used as markers to keep ones’ mental health in check. The components of FoMO and loneliness are also far more specific than the overarching concerns of anxiety and depression frequently associated with prolonged social media use. With there being increasing evidence indicating a correlation between FoMO or loneliness with depression, anxiety, or addiction-related mental health concerns, therapy programs can address issues more specific to young people (Baker et al., 2016; Hughes et al., 2004; Riordan et al., 2018).

With the time trackers that have recently been integrated into the Instagram app, users benefit from monitoring their daily consumption on Instagram. Thus, if they are consistently spending more than one hour daily, they may use this time as an indicator to keep a check on their overall mental health.

Moreover, posting selfies, memes, vlogs, emojis, and textual messages on Instagram and curating a complex online persona are increasingly becoming tools to understand the social media environment. It is also an opportunity to investigate how young users of Instagram understand the visual culture that surrounds them and showcase the socially constructed images of their social life amongst their network.

Limitations

The study has a few limitations that should be noted. The studied variables were collected by self-report, entailing the risk of obtaining socially desirable responses. The scales that measure FoMO and loneliness were short forms that may not be as sensitive as the full scale to pick up nuanced characteristics of the two variables, although the short forms make the scales most suitable for surveys. Future research can examine individuals’ specific preferences and motivations for engaging with Instagram for long periods and identify a more accurate threshold of time that one can spend on Instagram without being at risk for mental health concerns.

Conclusion

Instagram as a visual social media platform contributes to a feeling of FoMO and loneliness amongst young people in India. It generates a desire to belong, which manifests itself on Instagram posts. People frequently using this application need to understand how it could affect their psychological state. The study finds that the time spent on Instagram is a FoMO driven exercise that affects its users’ psychological well-being, as they suffer from loneliness. Therefore, the more time users spend on Instagram, the more likely they are to experience increasing levels of FoMO and loneliness. Feeling lonely or fearing being left out can arise due to internalised beliefs of being ‘unpopular’ or ‘unfunny,’ caused due to a lack of instant gratification via likes and views on the social media feed (Przybylski et al., 2013).

This study expands on studies exploring associations between social media use, FoMO, and a range of mental and physical health outcomes for young Indians. It also contributes to new literature aspects, such as information regarding the Instagram platform.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the anonymous reviewers, those who provided feedback related to the research, and to the participants who took out time to share their experiences.

Funding & Disclosure Statement

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

Abel, J. P., Buff, C. L., & Burr, S. A. (2016). Social media and the fear of missing out: Scale development and assessment. Journal of Business & Economics Research, 14(1), 33-44. https://doi.org/10.19030/jber.v14i1.9554

Abbott, W., Donaghey, J., Hare, J., & Hopkins, P. (2013). An Instagram is worth a thousand words: An industry panel and audience Q&A. Library Hi Tech News, 30(7), 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1108/LHTN-08-2013-0047

Appel, H., Gerlach, L. A., & Crusius, J. (2016). The interplay between Facebook use, social comparison, envy, and depression. Current Opinion in Psychology, 9, 44-49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.10.006

Baker, Z. G., Krieger, H., & LeRoy, A. S. (2016). Fear of missing out: Relationships with depression, mindfulness, and physical symptoms. Translational Issues in Psychological Science, 2(3), 275–282. https://doi.org/10.1037/tps0000075

Belk, R. W. (1988). Possessions and the extended self. Journal of Consumer Research, 15(2), 139-168. https://doi.org/10.1086/209154

Blachnio, A., Przepiorka, A., Balakier, E., & Boruch, W. (2016). Who discloses the most on Facebook? Computers in Human Behaviour, 55(Part B), 664-667. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.10.007

Blachnio, A., Przepiorka, A., Boruch, W., & Bałakier, E. (2016). Self- presentation styles, privacy, and loneliness as predictors of Facebook use in young people. Personality and Individual Differences, 94, 26-31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.12.051

Cooper, A. (2017). What is brain hacking? Tech insiders on why you should care [video]. CBS News. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/brain-hacking-tech-insiders-60-minutes/

Clayton, R. B., Leshner, G., & Almond, A. (2015). The extended iSelf: The impact of iPhone separation on cognition, emotion and physiology. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 20(1), 119-135. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12109

Clement, J. (2020, July 24). Countries with the most Instagram users 2020. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/578364/countries-with-most-instagram-users/

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic Motivation and Self- Determination in Human Behavior. Plenum Press. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-2271-7

Dibb, B., & Foster, M. (2021). Loneliness and Facebook use: The role of social comparison and rumination. Heliyon, 7(1), 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e05999

eMarketer Editors (2019, May 27). eMarketer reduces US Time spent estimates for Facebook and Snapchat: Instagram bucks trend will grow by 1 minute this year. eMarketer. https://www.emarketer.com/content/emarketer-reduces-us-time-spent-estimates-for-facebook-and-snapchat

Fardouly, J., Diedrichs, P. C., Vartanian, L. R., & Halliwell, E. (2015). Social comparisons on social media: The impact of Facebook on young women’s body image concerns and mood. Body Image, 13, 38-45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2014.12.002

Frison, E., & Eggermont, S. (2017). Browsing, posting and liking on Instagram: The reciprocal relationships between different types of Instagram use and adolescents ‘depressed mood. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 20(10), 603-609. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2017.0156

Hampus, J., & Lood Thelandersson, E. (2020). Relating URL to IRL: Social media usage and FoMO’s associations to adolescent well-being [LUP Student Papers, Lund University Libraries]. https://lup.lub.lu.se/student-papers/search/publication/9001526

Haynes, T. (2018, May 1). Dopamine, smartphones & you: A battle for your time. Harvard University. https://sitn.hms.harvard.edu/flash/2018/dopamine-smartphones-battle-time/

Hootsuite. (2021, January 27). Instagram demographics in 2021: Important user stats for marketers. https://hootsuite.widen.net/s/zcdrtxwczn/digital2021_globalreport_en

Hunt, M. G., Marx, R., Lipson, C., & Young, J. (2018). No more FoMO: Limiting social media decreases loneliness and depression. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 37 (10),751-768. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2018.37.10.751

Hughes, M. E., Waite, L. J., Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2004). A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys: Results from two population-based studies. Research on Aging, 26(6), 655–672. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027504268574

Kohler, M. T., Turner, I. N., & Webster, G. D. (2020). Social comparison and state-trait dynamics: Viewing image-conscious Instagram accounts affects college students’ mood and anxiety. Psychology of Popular Media. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000310

Kraut, R., Patterson, M., Lundmark, V., Kiesler, S., Mukopadhyay, T., & Scherlis, W. (1998). Internet paradox. A social technology that reduces social involvement and psychological well-being? American Psychologist, 53(9), 1017-1031. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.53.9.1017

Kruger, D. J., & Djerf J. M. (2016). Hing ringxiety: Attachment anxiety predicts experiences of phantom cell phone ringing. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 19(1), 56-59. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2015.0406

Lup, K., Trub, L., & Rosenthal, L. (2015). Instagram #Instasad?: Exploring associations among Instagram use, depressive symptoms, negative social comparison and strangers followed. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 18(5), 247-252. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2014.0560

Lutz, S., & Schneider, M. F. (2020) Is receiving Dislikes in social media still better than being ignored? The effects of ostracism and rejection on need threat and coping responses online. Media Psychology. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2020.1799409

Madden, M., Lenhart, A., Cortesi, S., Gasser, U., Duggan, M., Smith, A., & Beaton, M. (2013, May 21). Teens, social media and privacy. Pew Research Centre. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2013/05/21/teens-social-media-and-privacy/

Mahajan, R. (2013). Narcissism, loneliness and social networking site use: relationships and differences. AP J Psychological Medicine,14(2), 134-40.

Mahoney, J., Le Moignan, E., Long, K., Wilson, M., Barnett, J., Vines, J., & Lawson, S. (2019). Feeling alone among 317 million others: Disclosures of loneliness on Twitter. Computers in Human Behavior, 98, 20–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.03.024

Moore, K., & Craciun, G. (2020). Fear of missing out and personality as predictors of social networking sites usage: The Instagram case. Psychological Reports. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033294120936184

Morahan-Martin, J., & Schumacher, P. (2000). Incidence and correlates of pathological Internet use among college students. Computers in Human Behavior, 16(1), 13-29. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0747-5632(99)00049-7

Nie, N. H. (2001). Sociability, interpersonal relations, and the internet: Reconciling conflicting findings. American Behavioral Scientist, 45(3), 420-435. https://doi.org/10.1177/00027640121957277

Nie, N. H., Hillygus, D. S., & Erbring, L. (2002). Internet use, personal relations and sociability: A time diary study. In B. Wellman & C. Haythornthwaite (Ed.), The internet in everyday life (pp. 215-243). John Wiley.

Nowland, R., Necka, E. A., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2017). Loneliness and social Internet use: Pathways to reconnection in a digital world? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 13(2), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691617713052

Perlman, D., & Peplau, L. A. (1981). Toward a social psychology of loneliness. In R. Gilmour and S. Duck (Ed.), Personal relationships: Personal relations in disorder (pp. 31-56). Academic Press.

Pittman, M., & Reich, B. (2016). Social media and loneliness: Why an Instagram picture may be worth more than a thousand Twitter words. Computers in Human Behavior, 62, 155-167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.03.084

Primack, B. A., Shensa, A., Sidani, J. E., Whaite, E. O., Lin, L. Y., Rosen, D., Colditz, J. B., Radovic, A. M., & Miller, E., (2017). Social media use and perceived social isolation among young adults in the US. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 53(1), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2017.01.010

Przybylski, A. K., Murayama, K., DeHaan, C. R., Gladwell, V. (2013). Motivational, emotional, and behavioral correlates of fear of missing out. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(4), 1841-1848. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.02.014

Rajan, B. (2018). Fitness selfie and anorexia: A study of ‘fitness’ selfies of women on Instagram and its contribution to anorexia nervosa. Punctum. International Journal of Semiotics, 4(2), 66-89. https://doi.org/10.18680/hss.2018.0020

Reece, A. G., & Danforth, C. M. (2017). Instagram photos reveal predictive markers of depression. EPJ Data Science, 6(15), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1140/epjds/s13688-017-0110-z

Reiss, M. V., & Tsvetkova, M. (2019). Perceiving education from Facebook profile pictures. New Media and Society, 22(3), 550-570. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444819868678

Riehm, K. E., Feder, K. A., Tormohlen, K. N., Crum, R. M., Young, A. S., Green, K. M., Pacek, L. R., La Flair, L. N., & Mojtabai, R. (2019). Associations Between Time Spent Using Social Media and Internalizing and Externalizing Problems Among US Youth. JAMA Psychiatry, 76, 1266-1273. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.2325

Riordan, B., Cody, L., Flett, J., Conner, T., Hunter, J., & Scarf, D. (2018). The development of a single item FoMO (Fear of Missing Out) scale. Current Psychology, 39(4), 1215-1220. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-018-9824-8

Rozgonjuk, D., Sindermann, C., Elhai, J. D., & Montag, C. (2020). Fear of Missing Out (FoMO) and social media’s impact on daily-life and productivity at work: Do WhatsApp, Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat Use Disorders mediate that association? Addictive Behaviors, 110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106487

Russell, D., Peplau, L. A., & Cutrona, C. E. (1980). The revised UCLA Loneliness Scale: Concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39(3), 472-480. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.39.3.472

Ryan, T., & Xenos, S. (2011). Who Uses Facebook? An investigation into the relationship between the big five, shyness, narcissism, loneliness, and Facebook usage. Computers in Human Behaviour, 27(5),1658-64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2011.02.004

Salomon, D. (2013). Moving on Facebook: Using Instagram to connect with undergraduates and engage in teaching and learning. College & Research Libraries News, 74(8), 408-412. https://doi.org/10.5860/crln.74.8.8991

Sheldon, P., & Bryant. K. (2016). Instagram: Motives for its use and relationship to narcissism and contextual age. Computers in Human Behavior, 58, 89-97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.12.059

Song, H., Zmyslinski-Seelig, A., Kim, J., Drent, A., Victor, A., Omori, K., & Allen, M. (2014). Does Facebook make you lonely?: A meta analysis. Computers in Human Behavior, 36, 446-452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.04.011

Stapleton, P., Luiz, G., & Chatwin, H. (2017). General validation: The role of social comparison in use of Instagram among engineering adults. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 20(3), 142-149. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2016.0444

Tandoc, E. C., Ferrucci, P., & Duffy, M. (2015). Facebook use, envy, and depression among college students: Is Facebooking depressing? Computers in Human Behavior, 43, 139–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.10.053

Turkle, S. (2012). Alone together: Why we expect more from technology and less from each other. Basic Books.

Twenge, J. M., Joiner, T. E., Rogers, M. L., & Martin, G. N. (2017). Increases in depressive symptoms, suicide-related outcomes, and suicide rates among U.S. adolescents after 2010 and links to increased new media screen time. Clinical Psychological Science, 6(1), 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702617723376

Vogel, E., Rose, J., Roberts, L., & Eckles, K. (2014). Social comparison, social media, and self-esteem. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 3(2). 206-222. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000047

Wang, K., Frison, E., Eggermont, S., & Vandenbosch, L. (2018). Active public Facebook use and adolescents’ feelings of loneliness: Evidence for a curvilinear relationship. Journal of Adolescence, 67, 35-44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2018.05.008

Weiss, R. S. (1973). Loneliness: The experience of emotional and social isolation. The MIT Press.

Winter, J. (2013, July 23). Selfie-Loathing: Instagram is even more depressing than Facebook. Here’s why. Slate.

Yang, C. C. (2016). Instagram use, loneliness and social comparison orientation: Interact and browse on social media, but don’t compare. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 19(2), 703-708. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2016.0201

Yang, C. C., Holden, S. M., Carter, M. D. K., Webb, J. J. (2018). Social media social comparison and identity distress at the college transition: A dual-path model. Journal of Adolescence, 69, 92-102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2018.09.007