Consumer Value and Modes of Media Reception: Audience Response to Ryan, a Computer-animated Psycho-realist Documentary and its Own Documentation in Alter Egos

Recibido: 01/02/10

Aceptado: 27/04/10

Charles H. Davis, Ph.D.1, Florin Vladica, Ph.D.2

1 Edward S. Rogers Sr. Research Chair in Media Management and Entrepreneurship. School of Radio and Television Arts and Ted Rogers School of Management Rogers Communications Centre. Ryerson University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada. c5davis@ryerson.ca

2 Digital Value Lab. Rogers Communications Centre. Ryerson University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada. florin.vladica@ryerson.ca

Abstract

Consumer value and value creation are fundamental concepts in marketing, management and in literature on organizations, but are almost never considered in the context of screen-based “experience” products. In this paper, the authors depart from the prevailing approaches to audience or reception studies by investigating the experience value the consumption of a screen-based product has for the spectator. Using the Q-methodology and Holbrook’s consumer value framework (1999), they empirically identify audience segments based on television viewers’ subjective experience with an innovative film product: the award-winning, computer-animated short documentary Ryan. The film uses creative state-of-the art animation to tell a compelling story in ways that stretch the documentary genre. The authors uncover and describe four audience segments. Unexpectedly, these four segments bear a strong resemblance to the four principal modes of media reception proposed recently by Michelle (2007), thereby creating a potentially fruitful link between the framework for consumer experience value and media reception studies.

Key words: Consumer value, media reception, audience segments, creative animation, spectator, marketing.

Valor del consumidor y modos de recepción de medios: respuestas de la audiencia Ryan, un pequeño documental psicorrealista animado por computador, y su propia documentación en Alter Egos

Resumen

En mercadeo, administración y literatura sobre organizaciones, los conceptos de valor del consumidor y creación de valor son fundamentales, aunque casi nunca se examinan en el contexto de los bienes de experiencia en pantalla. En este artículo, nos apartamos de enfoques imperantes sobre audiencia o estudios de recepción y estudiamos el valor experimental que produce en el espectador el consumo de un producto visto en pantalla. Aplicando la metodología Q y el esquema de Holbrook sobre valor del consumidor (1999), identificamos segmentos de audiencia empíricamente, partiendo de la experiencia subjetiva de los telespectadores de un producto filmado de manera innovadora: Ryan, breve y laureado documental animado por computador. Este documental utiliza el estado del arte de la animación creativa para contar una historia convincente en un estilo que amplía el género documental. Descubrimos y describimos cuatro segmentos de audiencia que, sin que nos lo propusiéramos, se parecen mucho a los cuatro modos principales de recepción de medios, planteados recientemente por Michelle (2007). Esto crea un vínculo potencialmente útil entre el esquema sobre el valor experiencial del consumidor y los estudios sobre recepción de medios.

Palabras clave: valor del consumidor, recepción de medios, segmentos de audiencia, animación creativa, espectador, mercadeo.

Introduction

Media organizations, like producers in other experience industries, face the well-known problem of high uncertainty of demand for their products (Caves, 2000). Attraction and retention of audiences is a central challenge that media firms must face (cf. Aris and Bugin, 2005). To strengthen audience engagement and improve predictability and market control require making sense of audience motives and behavior. However, what feedbacks permit producers and purveyors of mediated experience goods to understand the ways these goods create value for consumers? Media industries, especially those branches that depend on advertising-supported business models, have developed highly rationalized feedback mechanisms to provide information about market share or customers’ exposure to product. These feedbacks, however, do not get at the subjective consumption experience. Professional or amateur critics or consumers themselves usually assess feedback about the consumption experience; they routinely share opinions about experiential product quality through word-of-mouth.

Market share, levels of exposure and vernacular opinions are, of course, far from negligible as sources of market intelligence, but they only take us so far in our attempt to understand sources of value creation in experience goods. The concepts of customer/consumer value and value creation are central ones in the marketing, management, and organization literatures, but they are infrequently considered in the context of screen-based experience goods. In this paper, we depart from prevailing approaches to audience or reception studies by investigating the experiential value that consumption of a screen product yields to the spectator. Using Q-methodology and Holbrook’s consumer value framework (1999), we empirically identify audience segments based on viewers’ subjective experience of an innovative-filmed product, the award-winning short computer-animated documentary Ryan. This film uses state-of the art creative animation to tell a compelling story in ways that stretch the documentary genre. We uncover and describe four audience segments. Unexpectedly, these four segments bear a strong resemblance to the four principal modes of media reception recently proposed by Michelle (2007), creating a potentially fruitful link between the experiential consumer value framework and media reception studies.

Screen Experiences, Innovation and Consumer Value in Documentary Film

Documentaries traditionally are considered to be a factual, non-fictional genre that seek to record, reveal, preserve, persuade, promote, analyze, question, or express a viewpoint (Renov, 1993), thereby making a pledge to the viewer “that what we will see and hear is about something real and true –and, frequently, important for us to understand” (Aufderheide, 2007). John Grierson coined the term documentary in 1926 in reference to the film Moana, produced by the American John Flaherty, which Grierson regarded as having a “documentary value” (Kilborn & Izod, 1997: 12). Documentary subgenres include advocacy, political propaganda and government affairs, historical, nature, and ethnographic (Aufderheide, 2007). Hogarth suggests that a global approach to documentaries should involve a “flexible definition of documentary to suit the social, cultural, economic, and technological circumstance in which it now operates” (2006, p.14), keeping in mind emerging demand for documentaries that provide “artful entertainment” (Aufderheide, 2005) and not just instruction or edification. Much scholarship on documentaries focuses on aesthetic innovation through critical analysis of documentary content, characterization and interpretation of stylistic features, parsing of a documentary film’s claims to authenticity, or grappling with the perennial question of what are the limits of the genre, considering the “increasingly blurred boundaries between factual and fictional genre categories” (Kilborne, 2004). This is true of the subgenre of documentary discussed here, animated documentary, which emphasizes an alternative means of conveying social or political messages rather than claiming to document something in the factual, non-fictional, or literal sense (Hight, 2008a, 2008b; Martins, 2008a).

Although documentaries are a strength of the Canadian screen industry, many documentary producers live a hand-to-mouth existence. Innovation in documentary business practice may provide the potential to put documentary production companies on a firmer financial footing. In a previous paper (Vladica & Davis, 2009), we described and assessed a model to analyze innovation in the Canadian documentary film industry. The Sawhney-Wolcott-Arroniz “radar” model of innovation (2006) identifies twelve dimensions of innovation and value creation. This model provides a comprehensive way of conceptualizing and observing innovation across all aspects of business practice in any industry, including a creative industry such as documentary film. It has one shortcoming, however: that limits its applicability in a significant swath of the economy: one of the twelve dimensions of innovation is a black box called “customer experience.” Reliable theory about the production of experiential value for screen audiences is scarce. A considerable literature in experiential marketing and customer value has emerged, but it has not affected mainstream innovation practices in the screen industries. Screen audience research has taken a different tack. Since the 1920s, a substantial audience research and analysis industry has emerged alongside the media industries. Napoli (2008) recounts how media organizations moved from reliance on intuitive understanding of audiences to development feedback mechanisms based on highly rationalized audience measurement practices with the emergence of advertising-supported broadcasting and the spread of consumption culture in the United States. Conceptualization of audiences and construction of coherent images of audiences are becoming increasingly complex undertakings as media consumption migrates to broadband. Highly mediated, interactive environments are leading to sharp increases in media consumption, high levels of personalization, proliferation of experience segments, and the advent of cross-platform “liquid media” (Russell, 2008). The once relatively distinct roles of consumer, spectator, user, and player overlap, and media such as social network sites lend themselves to multidimensional uses and gratifications (Joinson, 2008). Media consumption over interactive networks is leading to the sort of large transactional databases and data-intensive behavioral constructions of audiences and markets that have already become familiar to firms in retailing, financial services, and other sectors (Zwick and Dholakia, 2004), permitting precise targeting of advertisements and increasingly relevant product recommendations.

The motion picture industry stands apart from other screen industries in its reliance on spectacle and a one-to-many business model. Interactivity is not significant, and advertising is not the principal source of revenue. Hollywood’s business model requires production of blockbusters and recovery of high up-front product development costs through theatrical admission fees, brand extensions, windowing, and merchandising. Market research on film audiences took off in Hollywood in the 1940s (Bakker 2003). It has primarily evolved in three directions: focus groups and concept testing before release, audience profiling based on box office data, and investigation of the factors that affect consumers’ decision to see particular films or prefer various kinds of firms (Austin, 1986; Becker et al., 1985; Cuadrado and Frasquet, 1999; Fischoff, 1998; Moller & Karppinen, 1983; Palmgreen et al. 1988).

The field of scholarly research on screen audiences, however, has hotly debated the processes and consequences of audiencehood for decades. The contested status of the audience involves a methodological and epistemological controversy over the relative extent to which we can attribute effects to media consumption. These are the degree of activeness or passivity of the audience, the coherence of categories of audience, the motivations for categorizing audiences, and the implications of attributing or failing to attribute functions of consumer, producer, or citizen to audiences. Recent calls for methodological pluralism in audience research (e.g. Schroder et al., 2003) may help to widen the space of shared understanding between marketing and media studies which, as Puustinen (2006) points out, are both keenly interested in the subjective dimension of media consumption.

In this paper, we leave aside the sociodemographic and qualitative-interpretive approaches that are usually employed in research on audiences and their screen experiences, and use Q, a structured qualitative research methodology (described below), to focus entirely on the cognitive and affective responses of viewers to a specific screen experience. At first glance, the approach that is closest to our interests in the field of media studies may appear to be the uses- and-gratification paradigm. We are especially interested in the ways that content yields value, however, and this is a well-known weakness of the uses-and-gratifications approach. Instead, we employ the concept of customer value as a starting point. The three predominant meanings of customer value refer to value for the customer, shareholder value, and stakeholder value (Woodall, 2003). While conventions have been developed to define and measure shareholder and stakeholder value, the conceptualization and measurement of customer value remains unsettled. Korkman identifies three different starting points in the customer value literature: customer value as a cognitive process, as a resource-based production process, and as an experiential process. The latter –customer value as experiential process– has become a widely accepted proposition since Holbrook and Hirschman suggested in 1982 that the experiential dimension of consumer behavior is, in many cases, more important than considerations of functionality or price in production of consumption value. Therefore, marketing of experience goods cannot rely on conventional marketing frameworks that that assume consumers’ rational assessment of price and quality of offerings (Hirschman, 1983; see the useful summary in Euzeby, 1997).

Production of valuable customer experience is a central purpose of firms in experience industries, and failure to apprehend and understand innovation in customer experience is an important shortcoming among producers of experience goods. As the literature on service innovation makes clear, a complete understanding of customer experience innovation requires consideration of how an experience good produces value throughout the entire customer transaction cycle. In experience goods that aim primarily to yield entertainment value, such as films, arguably the core value is yielded during the consumption of the experience good. At present, however, reliable knowledge is scarce about the subjective dimensions of mediated consumption experiences. In particular, no conventions have been established; by which to observe and compare the ways that consumption of screen products creates value among audiences. This is especially true of documentary audiences (Austin, 2007, 2005; Eitzen, 1995; Hardie, 2008; Vladica & Davis, 2009).

Researchers have proposed and tested a variety of typologies of customer value but for which few validated scales are available. We used Holbrook’s (1999) typology of consumer value, which posits three dimensions of value: self-oriented vs. other-oriented, active vs. reactive, and extrinsic vs. intrinsic. This typology contains eight kinds of consumer value: efficiency, play, quality, beauty, status, ethics, esteem, and spirituality. Researchers have not yet begun to test customer/consumer value frameworks in the realm of experience goods, especially screen products. It is likely that some of the consumer value categories will need to be modified or left aside. For example, functional or instrumental value is not likely to be applicable in the case of film viewing.

Our goal in this paper is to identify and describe segments of audience experience. Consumer segmentation is a fundamental marketing practice that seeks to identify sets of potential or actual consumers with some common attributes that can be addressed with an offering. The sets can be defined using many different kinds of variables: “geographic, demographic, psychological, psychographic or behavioural” (Tynan and Drayton, 1987) and a range of increasingly sophisticated analytical methodologies (Wedel and Kakamura, 1999). We use Q-methodology, an exploratory empirical social science technique, to identify and describe the subjective viewpoints of viewers of an animated documentary film, Ryan, winner of the 2004 Oscar for best-animated short film.

Ryan and Alter Egos

Although best known for its stunning computer generated animation, Ryan claims documentary status through its portrayal of Ryan Larkin, renowned Canadian hand-drawn animation artist from the 1960s and 1970s. The film recount his downfall from wunderkind filmmaker to cokehead and alcoholic and homeless panhandler. Although the film points to a kind of redemption for Ryan, filmmaker Chris Landreth’s portrait of this fallen creator raises troubling questions about artistic license, especially when the short animated film is viewed as an embedded sequence in Laurence Green’s 52-minute live-action documentary Alter Egos (2004). Although originally, it was a promotional vehicle for Ryan, Alter Egos stands as a powerful documentary in its own right by chronicling the production of Ryan, notably including Larkin’s pained reaction to his psychorealistic portrayal in the film and the ensuing interaction between Larkin and Ryan’s creator Chris Landreth.3

Ryan Larkin (1943-2007) was a Canadian artist who learned animation at a young age at Canada’s National Film Board (NFB) in Montreal. He produced several acclaimed short animated films: Syrinx (1965), Cityscape (1966), Walking (1969), and Street Musique (1972).4 Walking, which was nominated for an Academy Award in 1970, is an astonishing five-minute portrayal of people moving on foot. It is a classic of handdrawn animation and some animation courses frequently use it as a teaching resource.

Considered a star in his 20s, Larkin never completed another film after Street Musique. He became addicted to cocaine and alcohol, and he ended up homeless, living in a men’s shelter in Montreal and panhandling for change. “I had a drug problem, you see,” recounts Larkin in Alter Egos.

That’s why I couldn’t finish my films. Cocaine. What you do in cocaine, is you get all kinds of brilliant ideas every three and a half minutes, and there’s never enough time to complete a thought on paper before another idea even more brilliant comes up. So I was overloading, which is the main reason why I stopped making films, because I was just not good at it anymore.

In 2000, a staffer from the Ottawa International Animation Festival “heard through a friend about this old animator who was now panhandling on the streets of Montreal” (Robinson, 2004). A group drove to Montreal to find him; “our idea was that maybe we could help him out by bringing him to the Ottawa 2000 festival” (ibid.). Larkin was indeed panhandling on St. Laurent Ave. He eventually was invited to join the festival’s selection committee. Robinson (2004) describes how the other animators on the selection committee became aware of the significance of Larkin’s contributions to animation:

We decided to have a screening of the committee’s own films. We consciously saved Ryan’s for last. The reaction was unforgettable. Until that moment, I do not think that Andrei, Pjotr or Chris really had an inkling that this guy was. When they saw Street Musique and Walking, they were stunned. “You did that film!?” someone said. In a span of about 20 minutes, Ryan went from little brother to mythological hero. Everyone wanted to know what happened, what he was doing. We poured drinks and everyone gathered around Ryan as he recounted — often through tears — his downfall from golden boy at the NFB to Montreal cokehead. Everyone was quiet. No one really knew what to say.

In following this encounter, Chris Landreth, engineer turned animator and member of the selection committee, began to develop the idea of a film based on Ryan’s life. Landreth, at the time employed by Alias, the maker of Maya and other 3D animation software, is the creator of several short animated films of which the best known before Ryan are The End (1995) and Bingo (1998).

I met Ryan Larkin in the summer of 2000. I hung out with him for one week and thought, “What a life story this guy has.” It has all the elements of drama. It’s got tragedy, comedy, absurdity, [and] this redemptive element. And there are some other themes as a result of it that are about Ryan, but also about alcoholism, addiction, mental illness and fear of failure. (Animating the Animator, 2007)

In the summer of 2001, Landreth conducted the series of interviews with Larkin that provided the audio for the film’s soundtrack and the video for modeling. It took about three years to complete the 14-minute film. The film recounts Landreth’s interview with Larkin in a decrepit cafeteria in a homeless shelter in Montreal, intercut with sequences from Larkin’s own animated films and observations about Larkin and his life by two individuals who knew him well, his former girlfriend Felicity Fanjoy and his former producer Derek Lamb. All characters are 3D CGI animated. The Landreth character shows the Ryan character an original drawing from Walking, the first time in 35 years that he has seen this original material. The climax occurs when the Landreth character asks the Ryan character to consider “beating alcohol in the same way you beat cocaine.” The Ryan character’s highly emotional response makes Landreth think of his mother, also a talented alcoholic who “died of it,” to whom the film is dedicated. The film ends with a scene of the Ryan character gracefully panhandling on a Montreal street, the Landreth character thoughtfully observing.

The story of Larkin’s fall and ambiguous redemption is made vivid with three-dimensional computer generated images to produce an expressive, surreal style Landreth calls psychorealism. It involves “co-opting elements of photorealism to serve a different purpose; to expose the realism of the incredibly complex, messy, chaotic, sometimes mundane, and always conflicted quality we call human nature” (Landreth, 2004, as cited in Power, 2009). Landreth’s psychorealism uses non motion-captured 3D graphics and simultaneous perspectives to make the physical appearance of the characters express their internal state of mind.5 Larkin himself is portrayed as a freakish skeletal figure with a disintegrating head in which we see images flashing. This stylistic feature exploiting faux photorealism to depict characters whose strange physical deformities represent their emotional lives elicited most attention among critics. Observed a reviewer in the New York Times,

The emotions are raw; so is the way Mr. Landreth draws the human mind. Ryan’s head looks like a botched medical experiment. Multicoloured strings cross and twist; red spikes strike his glasses when he gets angry. Green rays hang in empty space. Clear thought has burned away. (Jefferson, 2005)

Ryan takes three notable risks. First, it stretches the limits of documentary genre by asking viewers to accept 3D animation as a serious form when animation is usually experienced in cartoons, children’s programming, video games, or advertisements. Second, it requires that the viewer accept that non-factual photorealistic representations of characters’ appearances accurately represent emotional reality. Third, the film requires the viewer to judge whether the filmmaker has fairly treated Ryan, raising questions of who benefits from artistic license and who has been co-opted by it: the filmmaker, his subject, or the viewer.

Obscured by the success of Ryan is Laurence Green’s live action documentary Alter Egos, commissioned by the National Film Board to document the making of Ryan. Alter Egos provides a deeper and more detailed look at Larkin’s history and conflicts than Ryan does, and it crucially shows the complicated relationship that develops between filmmaker Landreth and his subject Larkin. The latter clearly has no inkling that he has been portrayed as a damaged skeletal figure in Landreth’s film until Landreth returns to Larkin’s shelter and shows him a videotape of the completed film, a scene that is shown in Alter Egos. Larkin’s reaction and the subsequent conversation between Landreth and Larkin create an extraordinarily poignant scene. Larkin says: “I’m not very fond of my skeleton image... it makes me very uncomfortable.” And later: “it’s always easier to portray grotesque versions of reality.” As the film sinks in: “I guess it shows me for who or what I really am.” But at the close of the film, Larkin says to the camera: “I am what I am. I didn’t do anything wrong.... I just want out of this film.”6

Method

We used Q-methodology to identify and describe subjects’ experiences of viewing Ryan. In Qmethodology, respondents rank order items–in this case, statements about the film. Q-methodology provides a systematic, rigorous means of objectively describing human subjectivity through the combination of qualitative and quantitative analysis (Brown 1996, 1980; McKeown and Thomas, 1988). Many social science disciplines such as political science, marketing, psychology, sociology, public policy, marketing, and health care has used Q-methodology, but less often the humanities. The use of Q-methodology in audience research is relatively infrequent.

The audience was a class of second-year television production students in a media research methods course. We screened a 20-minute segment from Alter Egos beginning with the sequence in which Landreth enters the men’s shelter in Montreal in search of Larkin to show him the completed film, and ending with a live action scene with Larkin and Landreth sitting in a bar discussing the film. This segment contains practically all of the animated film Ryan.

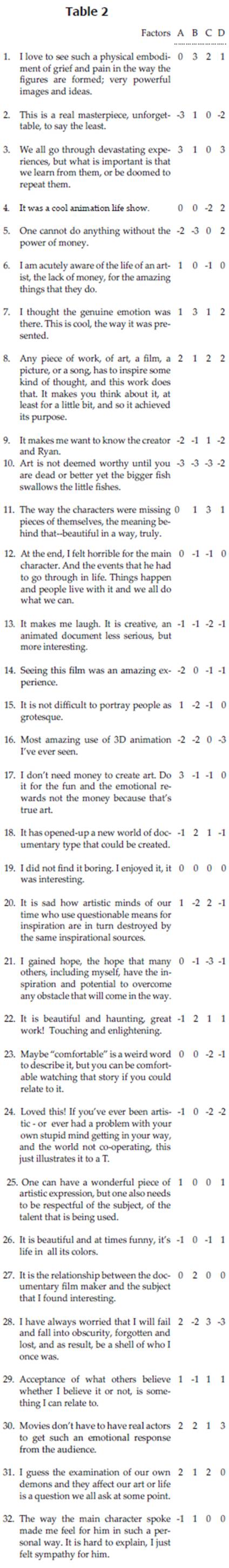

The items to sort (Q-deck) consisted of a “concourse” of 32 statements evoked by the film, shown in Table 2. A concourse must properly represent the range of ideas, feelings, and perceptions that the stimulus can evoke. We selected these statements from among several hundred collected from the audience, who was asked to write about their thoughts and feelings after having viewed Ryan, complementing the audience’s statements with a few selected from viewers’ comments posted to online film review sites. Since our research was motivated by the question of how a screen experience yields consumer value, we selected statements to represent the kinds of consumer value posited by Holbrook (1999). This was the most subjective step in our method because the existing concourse referred much more extensively to some kinds of consumer value than other kinds.

For example, we found no statements regarding ‘efficiency’ and few that we could classify as ‘play’ or ‘status.’ Our 32-statement concourse therefore does not adopt a balanced Fisherian design. The concourse contains nine statements referring to aesthetic value, nine on excellence, six on spiritual values, four on ethics, two on esteem, and one each on status and play.

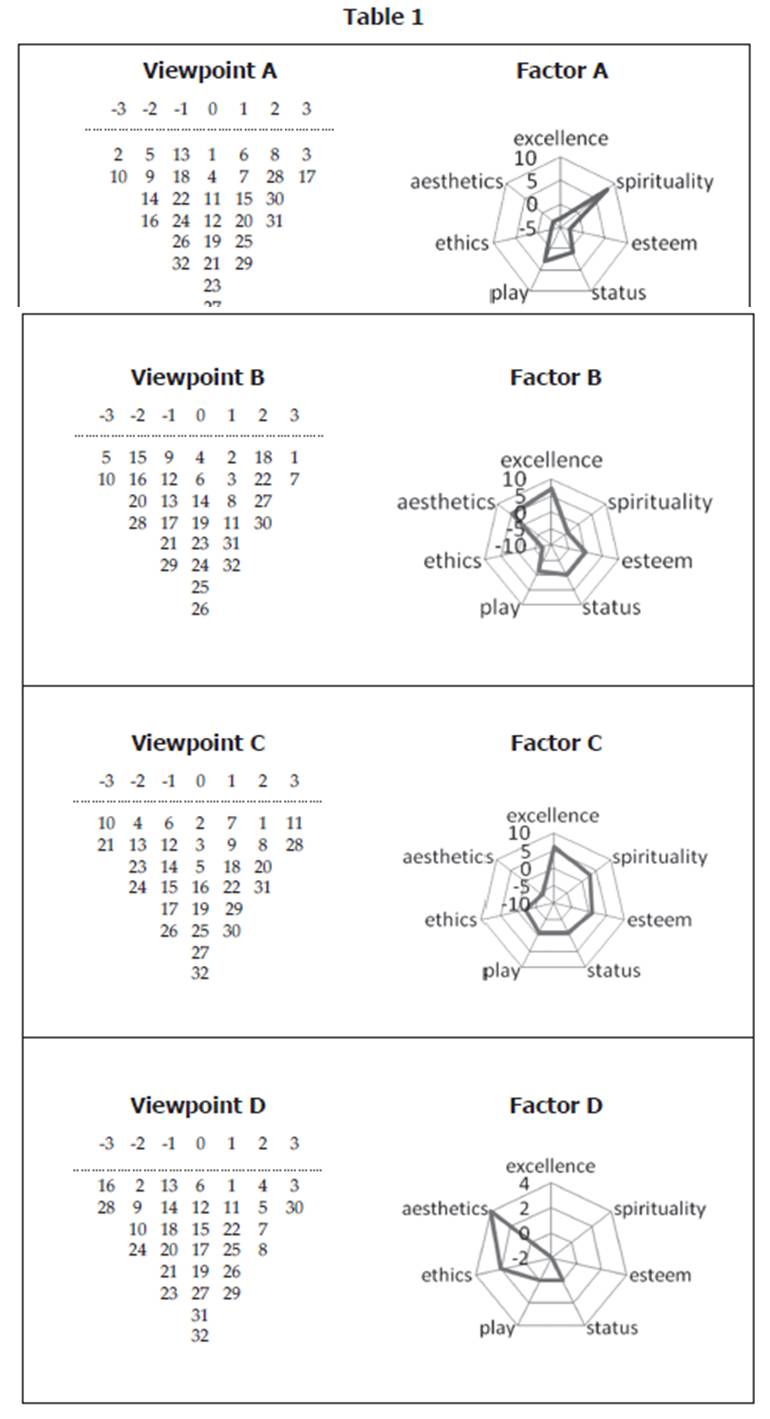

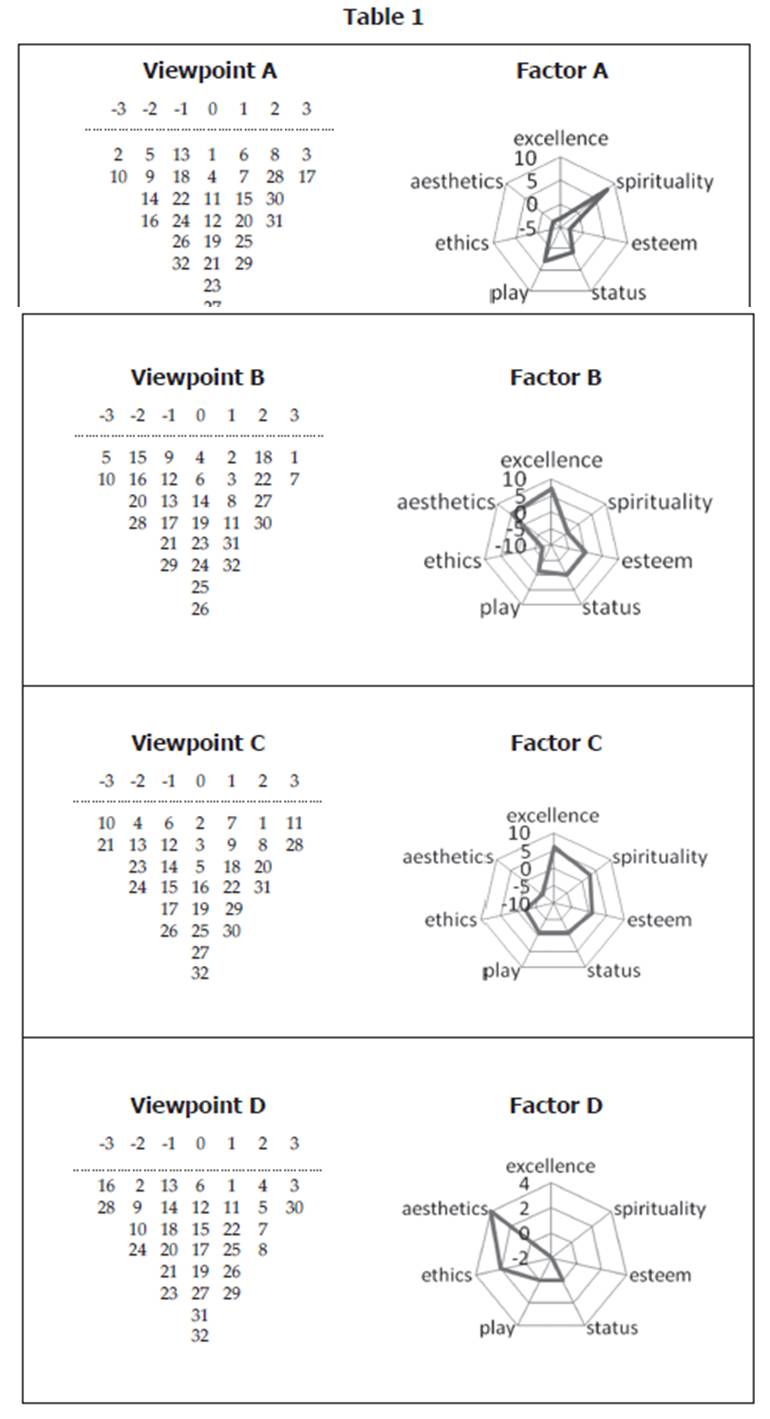

The audience anonymously completed the Q-sort a week after viewing the film. In this procedure, the respondent is asked to rank-order items by iteratively selecting the items that best and least represent his/her viewpoint, placing the items in a set distribution as shown in Table 1 and working toward the middle. We obtained 77 usable Q-sorts from participants this way and analyzed the results using a commercial software package for Q-methodology, PCQ for Windows.

Results

A four-factor solution fit the data best. In this solution, 48 sorts loaded significantly and singly on only one of the four factors. There were 5 confounded sorts and 24 non-significant sorts. Each factor had from 8 to 17 significant sorts associated with it. Each factor represents a viewpoint, an account of the viewer’s experience. The sorts that define each viewpoint are shown in Table 1, along with a radar diagram of the Holbrookian consumer values represented by each viewpoint.

A complete list of the 32 statements and the score of each statement on each factor are presented in Table 2.

Viewpoint A: Inspiring and Effective Work, but not a Masterpiece

Subjects respond as creative artists who identify with the animators in Ryan, although the story does not create a desire to know either Landreth or Ryan (statement 9). The film is considered inspiring by these subjects because it speaks to the “devastating experiences” familiar to creative artists (statement 3), the fear of failure and obscurity (statement 28), the need to examine one’s own demons and understand how they affect one’s art (statement 31), the dangers drugs pose to artistic persons (statement 20), and the intrinsic motivations for creating art (statement 17). Ryan is considered an effectively executed film because it uses computer-generated characters to achieve an emotional response (#30).

However, the film is not regarded as amazing (statement 14, statement 16) or an unforgettable masterpiece (statement 2). Subjects do not accept that money, death, or exploitation are necessarily part of the creative experience (statement 5, statement 10). In regards to sources of value and Holbrook’s model, viewpoint A expresses experience primarily in terms of spiritual values– faith, ecstasy, sacredness, and magic and relates largely to the numinous experiential aspects of the film. Seventeen respondents expressed this viewpoint.

Viewpoint B: Critical Appreciation for Powerful Documentary Storytelling

In Viewpoint B, subjects position themselves as knowledgeable documentary filmmakers, as craftpersons appraising a peer’s production. They respond primarily to Ryan’s value propositions in terms of its demonstration of the values of excellence and aesthetics (see Holbrook’s sources of value). They appreciate the techniques and approaches used to make the film and to convey the story. Subjects admire the film’s prowess at expressing beauty and emotion with computer-generated characters (statement 1, statement 7, statement 22), and indicate interest in the filmmaker-subject relationship (statement 27) as well as in Landreth’s innovation in the documentary genre (statement 18). Subjects do not respond emotionally to the film’s darker themes: fear of failure (statement 28), the association of art with a death wish (statement 10), or Larkin’s art-vs-commerce conflict (statement 5). Thirteen respondents expressed this viewpoint.

Viewpoint C: Powerful Story of Damaged Selves

In this viewpoint, subjects position themselves as individuals who empathize with the pain and suffering expressed by the characters in Ryan. Subjects respond emotionally to the depiction of damaged selves as damaged bodies and acknowledge their own fears of corporal or psychological disintegration (statement 1, statement 11), of “falling into obscurity” and becoming a shell (statement 28), and of destruction by internal demons (statement 31) or personal weaknesses related to drugs or alcohol (statement 20). Subjects do not find the film to be light, funny (statement 13), comfortable (statement 23), or reassuring (statement 21). This viewpoint reflects a screen experience that admires the quality of the animation finds the psychorealistic aesthetics painfully and effective. Eight respondents, female, expressed this viewpoint.

Viewpoint D: Cool Animation but not Engaging

In this viewpoint, subjects position themselves as sophisticated consumers of screen entertainment who decline to become engaged in this screen experience. They find the expression of emotion by computer-generated characters to be “cool” or a “cool show” (statement 7, statement 4, statement 30) and they admit that it induced “some kind of thought... at least for a little bit” (statement 8). They take it for granted that people have devastating experiences and that art can conflict with commerce (statement 3, statement 5). However, they do not worry about failure (statement 28) or art that seems driven by death wishes (statement 10), they do not want to get to know the artists (statement 9), and they do not regard the film as a masterpiece (statement 2) or amazing (statement 16). This viewpoint responds positively to the film’s proposed aesthetic and ethical sources of value, and negatively to its value propositions having to do with spirituality and craft excellence. Ten respondents expressed this viewpoint.

Discussion of Results

The four experience segments apprehend the film’s value propositions very differently. The audience does not place uniform value on the film in terms of excellence, spirituality, or aesthetics. In seeking to understand differences in viewers’ appraisals of the film’s value, we notice that each segment represents a specific way that the viewer positions him/herself with respect to the film. In Viewpoint A, viewers appraise the film as creative artists who relate to the film’s story of artistic genius and suffering. They find the film to be inspiring, so the source of value is of spiritual nature. In Viewpoint B, respondents position themselves as persons who have some knowledge of and interest in documentary filmmakers. They are interested in the creative beauty and craft excellence of the film, so notice film’s production values, including its problematic relationships between artist and subject. In Viewpoint C, viewers enter into the film and allow themselves to experience its narrative of self-damage. They admire the technical virtuosity of Ryan and find a spiritual appreciation, but the aesthetic style of the film is disturbing. In Viewpoint D, viewers keep themselves at arm’s length from the film. They find it mildly entertaining (play value) but do not wish to engage substantively with the film in terms of technique or narrative.

Descriptions of four distinct subjective viewpoints suggest that we can categorize viewers of Ryan in four audience segments. Since none of the four factors is bipolar, our audience did not experience Ryan in opposite ways, just different ways.

We can compare the four empirically identified viewer positions we uncovered with Q-methodology with a recently published theory of modes of audience reception. Michelle (2007) reviews the corpus of audience reception studies, synthesizes them, and proposes four modes of reception:

Our empirical findings show that audiences neither are passive consumers of screen messages, nor entirely individualized readers of texts. We found four viewpoints, representing segments of similar audience experience. The idiosyncratic experiencers are in a minority–they do not constitute a homogeneous group and the audience members in this group have only fragmentary aspects of their screen consumption experience to share with others–. These four principal experience segments, which we may represent the four principal modes of reception, as outlined by Michelle, account for 62% of respondents.

Conclusions and Implications

We are interested in the design, production, distribution, and especially consumption of experiential goods and services. In this paper, we looked at the subjective consumption experience of those who are watching an innovative-filmed product, the award-winning short computer-animated documentary Ryan. In order to describe and explain such a specific screen experience, we focused on the cognitive and affective responses of viewers. We empirically revealed four viewpoints, as described in the previous section, and we posit that combinations of different value types motivate and so can explain this range of responses. Holbrook’s framework for consumer value, with its typology of values, proved useful in a number of ways:

1. It helps to explain the diversity of viewpoints, hence different subjective screen experiences.

2. It helps in describing these viewpoints and, to a certain degree, the corresponding audience segments.

3. It provided a rationale for the selection of the statements required to construct the “concourse” in Q-methodology.

The subjects in our research project were second-year television production students. Their professional interest, career aspiration, and personal motivations can be captured with Holbrook’s typology of values and are nicely illustrated by the combination of value types that dominate their answers: excellence in craft and storytelling, the beauty of creative output, and source of personal inspiration and reflection (spirituality and esteem). At the same time, we do not equally capture all types of value in a concourse dominated by statements referring to “aesthetics” and “excellence”, nine each, whilst we found no statements regarding “efficiency”, and only one each on “status” and “play.” We suggest that future research should endeavor to adopt a balanced Fisherian design, work with a balanced concourse, and extend the research to a more heterogeneous audience. Perhaps this is also an indication for a need to refine the eight categories to better explain value created by experiential goods and services.

The eight types of consumer value proposed by Holbrook (1999) were used to select and build the concourse, the 32 statements sorted in Qmethod. In this sense, the typology can be a useful guide to design and implement early stages in Q-method. At the same time, this process of grouping statements according to types of value introduces a degree of subjectivity in the design of the research and interpretation of sorting performed. Furthermore, it requires in-depth familiarity with Holbrook’s interpretation of consumer value concept: not a trivial expertise to acquire.

Nevertheless, the use of Q-methodology was worthwhile in our endeavor to objectively identify and describe subjective experiences of viewing Ryan. In a broader context, we also conclude that there are promising prospects to adopt Qmethod in the study of audiences, of experiential consumption, and to better understand sources of value creation by experience goods. We were able to empirically identify audience segments, summarily characterize its members (given the limited data collected from subjects), and describe corresponding subjective viewpoints, all by working with both Q-method and Holbrook’s consumer value framework (1999). It was an unexpected outcome of our research to discover that these four empirically derived segments bear a strong resemblance to the four principal modes of media reception (Michelle, 2007).

These results encourage us to further look for ways to use Q-methodology at the boundaries between qualitative and quantitative research, between social sciences and humanities, to create fruitful links between these, such as the one between our experiential consumer value framework and media reception studies. Of course, we also recognize the need to adapt, to fine tune the tools and methodologies that brought us to this promising position. For example, the concourse in Q-method (the Q-sample) must properly represent the range of ideas, feelings, and perceptions that the stimulus can evoke. The viewpoints offered by media students apparently did not cover all eight types of consumer value, as discussed earlier. This may be related to our selection of subjects who performed the Q-sorts (the P-sample), a homogeneous demographic group, or may suggest the need for a better understanding of the applicability of Holbrook’s typology of value. It may very well be a limitation of this framework and its use in the context of media and creative products that should be addressed in future work.

We also confirm the potential that Q-methodology has for commercial research and managerial practice. As our example illustrates, the four factors (spectators’ viewpoints) enrich the market intelligence with empirically obtained knowledge, and consequently complement data and information from prevailing approaches to audience measurement. Most importantly, this knowledge of experiential value that consuming screen-based experience goods yield to the spectator is essential. Understanding the nature, the types, and the sources of experiential value, in other words making sense of audience motives and experience, can greatly improve predictability of a positive outcome and consequently critical acclaim or commercial success.

To strengthen audience engagement, media producers, for example, can use Q-method and conceptual models of experiential value to investigate and develop new mixes of characters or alternative storylines. Additional insights about individual behavior and preferences when acting as users, consumers, players, or members of an audience can be used in subsequent consumer research, to design advertising campaigns, and enhance effectiveness in promoting particular media brands. Understanding consumption experiences can enhance the range of services available at the venue before, during, and after a film screening, translated later on in increased satisfaction and larger boxoffice revenues. Finally, Q-methodology does not require large samples of respondents, it can be quickly executed, and finally it can result in lower cost intelligence whilst still offering rich qualitative and quantitative data, benefits largely appreciated by firms.

3 The film Ryan may be viewed on the National Film Board’s website (www.nfb.ca). The DVD Ryan (Special Edition) (2005) contains the film Ryan as well as the documentary Alter Egos.

4 These films may be viewed on the NFB website.

5 For an account of the 3D techniques used to create Ryan, see Robertson (2004).

6 Larkin came to appreciate the film Ryan, which helped to bring him out of the world of panhandling and back into the world of art. In a short video by Gibran Ramos titled “Ryan after Ryan,” shot the day Larkin received his diagnosis of a cancer that was to prove fatal, Larkin is seen wearing a t-shirt featuring Ryan’s skeletal face. Larkin says: “I was retired but because of Christopher Landreth and his famous film, I began to realize that there are millions of people out there wanting to see another Ryan Larkin film. I’ve been working on it.” http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a7QvVYz4Vzs.

References Animating the Animator. (2007). Amalgamated Perspectives, Sept. 14. http://instaplanet.blogspot.com/2007/09/animating-animator.html Aris, A. & J. Bughin, J. (2005). Managing media companies: Harnessing creative value. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. Aufderheide, P. (2007). Documentary film: A very short introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Aufderheide, P. (2005). The changing documentary marketplace. Cineaste, Summer, 24-28. Austin, B. A. (1986). Motivations for movie attendance. Communication Quarterly 34(2), 115-126. Austin, T. (2007). Watching the world: Screen documentary and audiences. Manchester: Manchester University Press. Austin, T. (2005). Seeing, feeling, knowing: A Case Study of Audience Perspectives on Screen Documentary. Particip@tions, 2(1), 36 pp. Bakker, G. (2003). Building knowledge about the consumer: The emergence of market research in the motion picture industry. Business History, 45(1), 101-127. Becker, B. W., Brewer, B., Dickerson, B., & Magee, R. (1985). The influence of personal values on movie preferences. In B. A. Austin (Ed.), Current research in film: Audiences, economics, and law (pp. 37-50). Vol. 1. Norwood, NJ: Ablex. Braun, J. (2005, January 27). Life of Ryan. Vue Film Weekly, 484 Brown, S. R. (1996). Q Methodology and Qualitative Research. Qualitative Health Research, 6, 561-567. Brown, S. R. (1980). Political subjectivity. Applications of Q Methodology in Political Science. New Haven: Yale University Press. Caves, R. (2000). Creative industries. Contracts between Art and Commerce. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Cuadrado, M. & Frasquet, M. (1999). Segmentation of Cinema Audiences: an Exploratory Study Applied to Young Consumers. Journal of Cultural Economics 23: 257–267. Eitzen, D. (1995). When is a Documentary? Documentary as a mode of reception. Cinema Journal, 35, 81-102. Eliashberg, J. & Sawhney, M. S. (1994). Modeling goes to Hollywood: Predicting individual differences in movie enjoyment. Management Science, 40(9), 1151-1173. Euzeby, F. (1997). Un état de l’art de la recherche en marketing dans le domaine cinématographique. Marketing des activités culturelles, touristiques et de loisirs. Actes de la Première Journée de Recherche de Bourgogne. Dijon: Université de Bourgogne. Fischoff, S. (1998). Favorite film choices: Influences of the beholder and the beheld, Journal of Media Psychology. 3(4). Hardie, A. (2008): Rollercoasters and reality: a Study of big screen documentary audiences, 2002-2007. Particip@tions, 5(1), 22. Hight, C. (2008a). The field of digital documentary: A challenge to documentary theorists. Studies in Documentary Film, 2(1), 3-7. Hight, C. (2008b). Primetime digital documentary animation: The photographic and graphic within play. Studies in Documentary Film, 2(1), 9-31. Hirschman, E. C. (1983). Aesthetics, ideologies and the limits of the marketing concept. Journal of Marketing, 47, 45-55. Hogarth, D. (2006). Realer than reel: Global directions in documentary. Austin: University of Texas Press. Holbrook, M. B. (1999). Introduction to consumer value. In M. Holbrook (Ed.), Consumer value: a framework for analysis and research (pp. 1-28). London and New York: Routledge. Holbrook, M. B. & Hirschman, E. C. (1982), The experiential aspects of consumption: Consumer fantasies, feeling and fun. Journal of Consumer Research, 9, 132-140. Jefferson, M. (2005, March 5). The short film, and art deserving a longer life, The New York Times. Joinson, A. (2008, April 5-10). ‘Looking at’, ‘Looking up’ or ‘Keeping up with’ People? Motives and uses of Facebook. CHI, 1027-1036. Kilborn, R. (2004). Framing the real: Taking stock of developments in documentary. Journal of Media Practice, 5(1), 25-32. Kilborn, R. Izod, J. (1997). An introduction to television documentary: Confronting reality. Manchester: Manchester University Press. Korkman, O. (2006). Customer value formation in practice: A practice-theoretical approach. Helsingfors: Swedish School of Economics and Business Administration. Martins, I. M. (2008a, August). Documentário animado: tecnologia e experimentação, On-line. Revista Digital de Cinema Documentário, 04, 66-91. Martins, I. M. (2008b). O documentário animado de Chris Landreth: experimentação e tecnologia. Comunicação e Cidanania-Actas do 5º Congresso de Associação Portuguesa de Ciências da Comunicação. Braga: Centro de Estudos de Comunicação e Sociedade McKeown, B. & Dan, T. (1988). Q-Methodology. Los Angeles: Sage Publications. Michelle, C. (2007). Modes of reception: A consolidated analytical framework. The Communication Review, 10(3), 181-222. Moller, K. & Karppinen, P. (1983). Role of Motives and Attributes in Consumer Motion Picture Choice. Journal of Economic Psychology, 4(3), 239-262. Napoli, P. M. (2008). The rationalization of audience understanding. Working Paper, Donald McGannon Communication Research Center. New York: Fordham University. Palmgreen, P., Cook, P L., & Harvill, J. G., & Helm D. M. (1988). The motivational framework of moviegoing: Uses and avoidances of theatrical films. In B. A. Austin (Ed.), Current Research in Film: Audiences, Economics, and Law. pp. 1-23, Vol. 4. Norwood, NJ: Ablex. Power, P. (2009). Animated expressions: Expressive style in 3D computer graphic narrative animation. Animation, 4(2), 107-129. Puustinen, L. (2006). The age of the consumeraudience. Conceptualising reception in media studies, Marketing and Media Organizations. Helsinki: Department of Communication, University of Helsinki, Working Paper 5/2006. Renov, M., Ed. (1993). Theorizing documentary. New York: Routledge. Robertson, B. (2004). Psychorealism –Animator Chris Landreth creates a new form of documentary filmmaking. Computer Graphics World, 27(7), 14-20. Robinson, C. (2004, May 3). The animation pimp rediscovers Ryan Larkin and Chris Landreth’s intimate short film on the fallen star animator, http://www.awn.com/category/columns/pimp?page=1. Retrieved September 21, 2009. Russell, M. G. (2009). A call for creativity in new metrics for liquid media. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 9(2), 44-61. Sawhney, M., Wolcott, R. C., & Arroniz, I. (2006). The 12 different ways for companies to innovate. MIT Sloan Management Review, 47(3), 75-81. Schiappa, E. & Wessels, E. (2007). Listening to audiences: a brief rationale and history of audience research in popular media studies. The International Journal of Listening, 2(1), 14-23. Schroder, K., Drotner, K., Kline, S. & Catherine Murray, Eds. (2003). Researching audiences. New York: Oxford University Press. Smith, J. B. & Colgate, M. (2007). Customer value creation: A practical framework. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 15(1), 7-25. Tynan, A. C. & Drayton, J. (1987). Market segmentation. Journal of Marketing Management, 2(3), 301-335. Vladica, F. & Davis, C. H. (2009). Business innovation and new media practices in documentary film production and distribution: Conceptual framework and review of evidence. In A. Albarran, P. Faustino & R. Santos (Eds.), The media as a driver of the information society. Lisbon: Media XXI/Formal Press and Universidade Catolica Editora. Wedel, M. & Kakamura, W. A. (1999). Market segmentation: Conceptual and methodological foundations. Amsterdam: Kluwer. Woodall, T. (2003). Conceptualizing ‘value for the customer’: An attributional, structural and dispositional analysis, Academy of Marketing Science Review, 2003(12). Zwick, D. & Dholakia, N. (2004). Consumer subjectivity in the age of the Internet: the radical concept of marketing control through customer relationship management. Information and Organizations, 14, 211-236. |