|

Artículo

Carolina Aguerre 1

Raquel Tarullo 2

1 ![]() 0000-0002-1968-062X. Universitát Duisburg-Essen, Germany; Universidad de San Andres, CETyS Argentina. aguerre@udesa.edu.ar

0000-0002-1968-062X. Universitát Duisburg-Essen, Germany; Universidad de San Andres, CETyS Argentina. aguerre@udesa.edu.ar

2 ![]() 0000-0003-2372-7571. Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET),

Argentina; CITNoBA, Argentina. mrtarullo@comunidad.unnoba.edu.ar

0000-0003-2372-7571. Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET),

Argentina; CITNoBA, Argentina. mrtarullo@comunidad.unnoba.edu.ar

* The authors' names are organized alphabetically. Both contributed equally to this paper.

** Los nombres de las autoras están organizados en orden alfabético. Ambas autoras trabajaron de manera equitativa en este artículo.

*** Os nomes dos autores estão organizados em ordem alfabética. O trabalho neste artigo foi distribuído equitativamente.

Recibido: 09/10/2020

Aprobado por pares: 16/07/2021

Enviado a pares: 13/01/2021

Aceptado: 09/08/2021

To reference this article / Para citar este artículo< / Para citar este artigo: Aguerre, C. & Tarullo, R. (2021). Unravelling Resistance: Data Activism Configurations in Latin American Civil Society. Palabra Clave, 24(3), e2435. https://doi.org/10.5294/pacla.2021.24.3.5

Abstract

This work examines the evolution of Latin American Civil Society Organizations' (CSOs) resistance practices in the context of datafication and how these relate with the overall notions of symbolic domination denounced by the Latin American School of Communication. Although CSOs in Latin America are still exploring the problems surrounding datafication, signs of vitality are already showing in broader debates around human rights, community development, and media policies. The study identifies the main themes underlying datafication work by Latin American CSOs and assesses how they shape resistance practices and CSOs' perceptions of asymmetrical power relations. While some patterns can fall into existing conceptualisations surrounding resistance practices and data activism, this paper identifies new conceptual and empirical approaches to face the challenges posed by a datafied society.

Keywords (Source Unesco Thesaurus): Datafied society; data colonialism; resistance; Latin America; civil society organizations.

Resumen

En este artículo, se indaga sobre las prácticas de resistencia de las organizaciones de la sociedad civil de América Latina en un contexto de datificación y en la forma en que estas se relacionan con las nociones de dominación simbólica que denuncia la Escuela Latinoamericana de Comunicación. Si bien la problemática de la datificación está aún en expansión como parte de la agenda de las organizaciones de la sociedad civil en el continente, ha demostrado signos de vitalidad a partir de su inclusión en debates más amplios que incluyen temáticas tales como derechos humanos, desarrollo comunitario y políticas de medios. Este estudio identifica las temáticas principales que integran el trabajo que llevan a cabo las organizaciones de la sociedad civil de América Latina, a la vez que examina cómo emprenden prácticas de resistencia y sus percepciones sobre las asimetrías en las relaciones de poder en este contexto. Mientras que ciertos patrones pueden inscribirse en conceptualizaciones existentes sobre prácticas de resistencia y activismo de datos, esta investigación identifica nuevos enfoques conceptuales y empíricos para enfrentar los desafíos que plantea una sociedad datificada.

Palabras clave (Fuente tesauro de la Unesco): Sociedad datificada; colonialismo de datos; resistencia; América Latina; organizaciones de la sociedad civil.

Resumo

Neste trabalho, indagam-se as práticas de resistência das organizações da sociedade civil latino-americana num contexto de datificação e como estas se relacionam com as noções de dominação simbólica denunciadas pela Escola Latino-Americana de Comunicação. Embora o problema da datificação ainda esteja em expansão como parte da agenda das organizações da sociedade civil no continente, tem mostrado sinais de vitalidade através da sua inclusão em debates mais amplos que incluem questões como os direitos humanos, o desenvolvimento comunitário e a política dos meios. Neste estudo, identificam-se os principais temas que compõem o trabalho dessas organizações, examinando a forma como estas empreendem práticas de resistência e suas percepções das assimetrias nas relações de poder nesse contexto. Embora certos padrões possam ser inscritos em conceptu-alizações existentes de práticas de resistência e ativismo de dados, esta pesquisa identifica novas abordagens conceituais e empíricas para enfrentar os desafios que surgem de uma sociedade datificada.

Palavras-chave (Fonte tesauro da Unesco): Sociedade datificada; colonialismo dos dados; resistência; América Latina; organizações da sociedade civil.

Introduction

Organised civil society in Latin America has long been involved in social justice and human rights agenda (Abregú, 2008), particularly over the last fifty years when military dictatorships have swept through most countries in the region. In recent decades, an understanding of this sector has been constructed against the different "domination" forms and sources tramping across the continent for centuries. As a result, civil society has forged an identity that challenges the material and symbolic foundations of the "natural order" based on asymmetric power relations between this sector and the political and economic establishment.

While civil society has shaped a tradition of resistance to broader notions of power and dominance with colonial roots, the spread of mass media and cultural industries following a commercial market approach that mirrors the US model was addressed by a particular sector of scholars, activists and thinkers that laid the foundations for the Latin American School of Communication in the 1960s. This eclectic movement (Gobbi, 2004) has consistently identified new forms of symbolic domination (García Canclini, 2004) emerging from a new form of material dominance relying on information and communication structures. Since its origins, it has engaged in interdisciplinary dialogues and practices involving researchers and activists, where Paulo Freire's communication-education model (Bambozzi, 2013) based on horizontal dialogues—acts of creation and social transformation (Freire, 1975)— stands out as a prime example.

A new form of symbolic domination (García Canclini, 2004) has emerged in the 21st century, understood as the hegemonic sectors' attempts to impose meaning(s) that consolidate specific ideologies (León Duarte, 2001), sustained by the expansion of digital networks and the advance of artificial intelligence (AI) and technological ubiquity in the "cyber-physical realm" (De Nardis, 2020, p. 225). The input —cooked data, as opposed to the notion of raw data questioned by several authors (Gitelman, 2013; Gutiérrez, 2018a, 2018b)— used by these underlying technologies and their business models are based on and supported by the capture, storage, accumulation, and processing of this asset (Zuboff, 2019). These processes are part of a more extensive set of global digital value chains whose anatomy replicates the colonial order of extraction (Crawford & Joler, 2018). However, the processing and transformation of data as an asset are epistemically much more complex than the analogy of "natural" raw material extracted during the European approaches to imperialism over the last five centuries: "We should not think of data as a natural resource, but as a cultural one that needs to be created, curated and elucidated" (Gutiérrez, 2018a, p. 8).

Academic circles mainly based in the "West" (Milan & Treré, 2019) have coined "data colonialism" as a form of exploitation and control that is no longer focused on the extraction of natural resources or human toil but on the appropriation of life from data, thus paving the way for a new stage of capitalism and value creation (Couldry & Mejias, 2019). The path of resistance to this new form ofcolonialism is complex for several reasons. First, "colonisers" vary in number, type, and capacity to mobilise people and resources —from companies to states— and their connections, which are less evident than in past empires. Second, many of the "colonised" do not have the skills to assess the multiple dimensions of the costs of this connected life (García Canclini, 2020), including the manipulation of choices and what could be deemed "epistemic violence."

In the last decade, civil society across the Latin American region has engaged in an agenda to reform media systems and the public sphere as they intersect digitisation (Becerra, 2014; Montoya-Londoño, 2010), platformisation, and datafication-based business models. Datafication is understood as "a contemporary phenomenon which refers to the quantification of human life through digital information, very often for economic value" (Couldry & Mejias, 2019, p. 2). Existing research has shown the links between data activism —sociotechnical mobilisations critically approaching data and data infrastructure (Milan, 2018)— in the region and new forms of journalism based on data practices, pointing at new forms of media and information outlets that can be adopted in a datafied setting (Amado & Tarullo, 2019; de-Lima-Santos & Mesquita, 2021; Milan & Gutiérrez, 2015).

This work seeks to understand how data activism in civil society organisations (CSOs) working at the intersection of human rights, data, and digitalisation interprets and interacts with data-based initiatives. It also aims to elucidate the challenges arising from datafication against the backdrop of Antonio Pasquali's "research-denunciation" approach, centred in the critiques of different forms of oppression through the media, and Paulo Freire's research-action proposal, where research is contemplated as a historically contextualised action in which participants define the process and objectives of knowledge (Freire, 1975). Both authors consider research to be a meaningful tool for resistance and addressing the material domain of communication and lay the groundwork in the 1960s for a critical approach to culture massification and the reinstatement of the role of popular cultures (Sánchez Navarte, 2014; Sunkel, 2006). Approaches to datafication have been heuristically organised to represent proactive and reactive stances (Milan & Gutiérrez, 2015): reactive in the traditional role of civil society's defence of human rights against impending mass surveillance and proactive in empowering new forms of civil resistance and information by taking advantage of the opportunities offered by "big data."

This exploratory research deploys discourse analysis to assess how CSOs in Latin America implement resistance and data activism practices at the intersection of human rights and the digital sphere. It aims to investigate forms of resistance through a data activism lens and their relationship to other micro-practices and perspectives that can configure different settings around reactive and proactive data activism (Gutiérrez, 2018a; Milan & Gutiérrez, 2015), as well as continuities and ruptures of the resistance role delimited by the Latin American School of Communication.

The Latin American School of Communication in a datafied context

The Internet and AI are both General-Purpose Technologies (GPT), whose combination has spurred the technical and material foundations for datafication. It has also increasingly positioned internet platforms as media players that perform information, entertainment, and educational functions, such as public broadcasting services, and act as gatekeepers of any discourse in the new public sphere (Dutta-Bergman, 2004; Leurdijk, 2007; Meraz, 2011). Two main types ofactors hold power in this context: technology companies, particularly those in Silicon Valley and China; and governments —the "informational state" (Braman, 2006)— as the most prominent data producers and controllers in most sectors (Calo, 2017; Ciuriak, 2018). Company services based on data analytics and opaque value chains and governments alike take advantage of datafication for their purposes. From surveillance to electoral campaigns or health services, data is an enabler of political power in the context of "computational politics" (Tufekci, 2014).

The Latin American School of Communication has traditionally conceptualised mass media construction as a form of symbolic domination (Marques de Melo, 1998; Pasquali, 1998). However, the proposal of digital media and mass self-communication (Castells, 2009) not only includes new technologies; it completely re-shapes information and content sources, means of production, and dissemination strategies. The traditional gate-keeping activities of mainstream media in the Latin American context and the problem of access for and inclusion of alternative or oppressed groups are the main issues for this school and have maintained continuities and differences over the years. On a community access level, literacy and appropriation are prevalent; and from a broader technopolitical perspective, there is resistance to algorithmic governance.

These digital platforms are fuelled by the data generated by sectors that use them for their resistance activities, but without controlling how these algorithms make decisions, rank, filter and organise this data (Treré, 2016). While the gates to these platforms are open, the rules are defined by the organisations that run them and shape the algorithmic preferences (Ricaurte, 2019; Srnicek, 2017), which poses significant challenges for the alternative discourse and practices of human rights civil society advocates (Peña & Varon, 2019).

Antonio Pasquali's "research-denunciation" approach (Gobbi, 2004; Pasquali, 2007) is a critical stance of resistance towards the non-dialogic construction of media systems that emerged within the Latin American School of Communication, directly influenced by the Frankfurt School. Pasquali's denunciation approach from 1970 is centred on denouncing four problems: (i) the expansion of imperialism and its undermining of Latin American people's sovereignty; (ii) the monopoly exercised by the political and economic power of local oligarchies; (iii) the media's lack of commitment with democratic values and cultural responsibility, and (iv) the processes of social domination and absence of dialogic processes in media and culture (Marques de Melo, 1999, as cited in Costa & Otre, 2019). More relevantly, this epistemological approach to communication states that knowledge is produced when we critically relate our field of cultural experience to reality (Pasquali, 2007; Valencia Rincón, 2012).

The critical approach of this author lies primarily in the third Haber-masian approach to knowledge as "liberating consciousness from the dependence on hypostatised powers" (Habermas, 2004, p. 318), which implied, in the Latin American context of the 1960s and 1970s, the liberation of knowledge by the oppressed, the marginalised, and non-mainstream voices. Datafication challenges the possibility of producing critical knowledge due to these systems' opaqueness, black-box mechanisms, and related institutional practices. Since knowledge production is never separate from the knowledge producer (Boellstorff, 2013), datafication challenges resistance practices while underscoring the authority of the research-denunciation approach in imposing non-dialogic systems of media and knowledge production.

Civil society in the region has sought to democratise media systems, including community broadcasting services and public broadcasting, to contest commercial models and alternative discourses excluded from mainstream social, political, and cultural narratives in the last half-century. This purpose aligns with the stance of the Latin American School of Communication, which has sought to unravel the hegemonic interests of commercially oriented media (Barranquero & Sáez-Baeza, 2012). These organisations working on advancing media freedom, media diversity, community media, and freedom of expression before the datafied world were integrated into the school's work as a locus of resistance against the media's symbolic control and hegemonic narratives (Pasquali, 2007). Nevertheless, new forms of resistance are required in an institutional and regulatory ecosystem with continuity of actors, such as the traditional media conglomerates that have adapted to the data-driven digital scenario.

In contrast, others have emerged with ever more intricate strategies (García Canclini, 2020). While the power of transnational digital media and data platforms is not radically different from that of communications actors in the past, it affects the capacity of CSOs and the research community to appropriately appraise the evolution of these informational flows and value capture. It also gives rise to new affordances, referred to as what an individual or organisation can accomplish with a particular technology (Majchrazak & Markus, 2014) and the possibilities for interaction they provide to different actors (Faraj & Azad, 2012).

Data activism as resistance

A datafied society poses a new set of threats that seek not only to depoliticize deeply political decisions (Hintz et al., 2019) but also to render opaque and unintelligible sources and mechanisms for these new power relations. In the tradition of the Latin American School of Communication, knowledge becomes a legitimising source for constructing democratic systems of communication that can serve as agents of change. For decades, this school has led dialogue and cooperation between academia and civil society in the conceptual and empirical domains nationally and internationally1.

Data activism is a theoretical construct that addresses a multidimensional and multidisciplinary phenomenon comprising a sociological domain (collective organisational capacity), a cognitive domain (providing meaning to complex settings), and sociotechnical practices focused on the technological foundations (Milan & Gutiérrez, 2015, p. 15). Data activism brings about new epistemic cultures pointing at a fundamental change in perspective and attitude towards datafication slowly emerging within the organised civil society (Milan & van der Velden, 2016, p. 62), spanning human rights, data policies, media regulation, digital citizenship, among others.

We find that this notion reverberates with Paulo Freire's education-knowledge approach as a principle that defines community work to empower citizens with voice and agency. Freire's work proposed an alternative communication paradigm based on research action (Freire, 1993), linked to Pasquali's critical claims of rejecting top-down communication models. Freire's proposal embraces dialogic participation where all participants have a voice for a proactive and horizontal interaction that fosters the transformation of their immediate context. This scheme circulates through an awareness-raising process that, for the Brazilian author, is key for the liberation of humankind (Freire, 1995).

Data activism is an umbrella term (Milan & Gutiérrez, 2015; Milan & van der Velden, 2016) that considers both data collection and use by civil society. It also openly disputes the use of data as a resource for exploitation for purely economic gains, as a battle against commodification, and the advancement of democratic participation (Gutiérrez, 2018a). It can be conceptualised as a form of resistance against the power of algorithmic governance and its key players from a technopolitical dimension (Gutiérrez, 2018a; Milan & Gutiérrez, 2017).

Even though data activism has been analysed to produce reactive and proactive approaches (Milan & Gutiérrez, 2015), data is also crossed by "contentious politics" (Beraldo & Milan, 2019), which delimits and underpins different scenes for action. Reactive approaches are based on protest, while proactive ones "bypass deadlocks and top-down approaches to social challenges; they correct asymmetries and empower individuals and groups to communicate, collaborate and participate in decision making processes" (Gutiérrez, 2018a, p. 3), fulfilling the gap that the research denunciation approach had warned against in terms of dialogic participation. Data activism is more crucially agentic than the research-denunciation approach. It addresses concrete materiality for intervention: the affordances (Gaver, 1991) of the digital environment are different from the context of broadcasting media, which regional civil society has begun to grasp more fully over the last decade. Data activism meets resistance as part of proactive data practices (Milan & Gutiérrez, 2015) that reconfigure notions of agency in some sections of civil society, particularly the open data movement (Baack, 2015), and addresses how datafication is also bringing about a shift in civic life itself (Gutiérrez, 2018b).

Several authors that have looked at civil society roles in the datafied space have mentioned reactive approaches and the difficulty to provide alternative paths of transformation (Hintz et al., 2019; Milan, 2015). Hintz and colleagues (2019) identify three modes of resistance based on existing civil society practices: self-protection against surveillance, lobbying around policy frameworks concerning datafication, and citizen-oriented initiatives based on data to subvert the existing order. These last two modes fall into the category of proactive data activism as categorised by Milan and Gutiérrez (2015), which can support prevailing activist stances and enhance new approaches and forms of citizen participation (Gutiérrez, 2018b, 2019).

Civil society resistance practices can be conceptualised as acting from "within" the institutional norms and boundaries, mainly through lobbying and capacity building to promote legal reforms such as Pasquali's "National Communications Policies,"2 but also from the margins, particularly with grassroots movements (Gutiérrez, 2018a; Hintz et al., 2019). Other forms of resistance in Latin American social movements have originated within social media itself; hashtivism, for instance, has managed to elicit movements that go beyond the digital sphere to shape public discourse and legislation around gender, abortion, and the environment (Tarullo & Frezzotti, 2020; Tarullo & García, 2020). Some of these initiatives have later become part of organised civil society efforts, such as #Niunamenos by Latin American feminist journalists (Chenou & Cespeda-Masmela, 2019), which later became a collective movement against gender violence primarily based on digital activism that has replicated in different countries even outside the region. Platforms such as Femicidios MX and CUIDATA in Mexico and Geochicas in Nicaragua3 have been developed to map gender violence using crowdsourced data.

Purpose and methodological approach

This research aims to understand how Latin American CSOs mount, understand, and narrate resistance in the context of datafication and how it addresses Pasqueali's and Freire's notions of denunciation, emancipation, and knowledge. The sociological, cognitive, and sociotechnical levels (Milan & Gutiérrez, 2015) of denunciation and resistance to media systems in the broadcasting era reflect significant differences with the material and sociotechnical dynamics of domination, exclusion, appropriation, and contestation ofthe digitally networked environment. What are the continuities and differences of the paradigm of denunciation emerging from the Latin American School of Communication in a datafied context? Are the practices and approaches to civil society's datafication resistance in the region in dialogue with the Latin American School of Communication's notions? To what extent are they opening new pathways?

Considering that the phenomenon of datafication is still in its early stages of development as part of the agenda ofCSOs in Latin America from a human rights approach and has been little studied from a Latin American perspective (Chenou & Cepeda-Masmelan, 2019; Gutiérrez, 2018a, 2018b; Siles et al., 2019), we conducted exploratory research with a descriptive scope (Hernández Sampieri et al., 2014).

The specific objectives of the study are:

1. To identify and explore the main themes underlying the work of Latin American CSOs on datafication;

2. To identify and assess CSOs' resistance practices in the region;

3. To examine Latin American CSOs' perceptions of power in the context of datafication.

Methods were triangulated to accomplish these aims. The empirical work was divided into three stages between June and September 2020. First, after using an inductive approach to the subject of study, we designed the pattern with the categories for selecting the CSOs. The selection criteria for these organisations relied on the following attributes: headquarters or a significant number of staff members based in a Latin American country; work with national or regional issues and stakeholders; focus on digital technologies —including data— and their impact on and intersection with human rights or sustainable development; and if the organisation had emerged in the last three decades, reflecting growth with the development ofthe underlying technologies that sustain current processes in datafied societies. Using these indicators, 17 CSOs were selected (Table 1). As data activism is not a singular approach of mission-driven CSOs, this sample allowed enquiring into different organisation types and agendas, from those with a focus on gender and feminist issues in the digital sphere to others concerned with digital public policy, online human rights, and civic technologies, including data for the public interest.

Table 1. Studied CSO by country

Organisation |

Country* |

Organisation |

Country* |

Access Now (Latin American office) |

Argentina |

ILDA |

Uruguay |

Asociación por los Derechos Civiles |

Argentina |

Internet Lab |

Brazil |

Coding Rights |

Brazil |

IPANDETEC |

Panama |

DATA Uruguay |

Uruguay |

Maria Lab |

Brazil |

Derechos Digitales |

Chile |

Observacom |

Uruguay |

Fundación Ciudadanía Inteligente |

Chile |

R3D |

Mexico |

Fundación Karisma |

Colombia |

Sula Batsu |

Costa Rica |

Fundación Vía Libre |

Argentina |

TEDIC |

Paraguay |

Hiperderecho |

Peru |

Note. *By country, we refer to the legal incorporation of

these organisations, not to their scope of action and

reach.

In many cases, these go beyond their countries' headquarters.

Source: Own elaboration

We then identified 592 documents posted on the websites of the CSOs included in the sample. We selected documents from the Publications tabs (or similar wording) that referred to data, data protection, and AI (n = 61). Thematic analysis followed to identify the main narratives in their approaches to data activism and resistance. These organisations have traditionally played a vital role in critiquing exploitation and human rights abuses online or using and examining the tools concerning this data exploration. The documents analysed consisted of press releases and reports (61 in total from 2015 to 2020; 70 % were posted in 2018-2020). For this phase, an instrument was designed to collect information concerning the objectives of the document.

However, the inductive approach for analysing the content posted on the studied CSOs' websites brought about the incorporation of new categories. For the resistance practices, we used Hintz et al.'s (2019) categories (surveillance, lobby, citizen-oriented initiatives) and Milan & Gutiérrez's (2015) reactive-proactive categorisation. Additional resistance categories emerged from the analysis, conceptualisation, and empirical understanding of resistance in a datafied society.

Finally, a narrative perspective was used to examine the characteristics of CSOs' resistance practices. To accomplish this, CSOs were approached by email, explaining the purposes of this research. Thirteen members of eleven organisations were interviewed (60 % men; 40 % women; eleven in the 30-40 age range; and two over 50 years old.) The interviews were semi-structured with an interview guide to capturing interview participants' comments (Ozonas & Pérez, 2005). This type of interview enabled participants to elaborate and researchers to identify unforeseen perspectives and broaden the meaning of certain concepts and their data practices (Díaz-Bravo et al., 2013).

This information was pieced together as part of the analysis to integrate the qualitative data collected (Valles, 1999). The interview guidelines facilitated responses around their perceptions of data mining and economic models based on data capture, storage, and processing in the current digital context in Latin America; their assessment of the challenges imposing old and new forms of exploitation and domination with and through data, including new forms of imperialism; and their approaches towards the data activist practices they follow and their implications for resistance.

These interviews were conducted online on September 1-15, 2020. The average length of the interviews was 24 minutes. They were recorded with the participants' consent with the disclaimer of anony misation of their comments. The transcribed interviews were analysed manually through a theme-centred analysis carried out in three stages: codification, classification, and integration (Valles, 1999). These qualitative results were combined with the information obtained from the website content analysis.4

Results and discussion

The findings of this research emerge from the thematic exploration of the documents published online (n = 61) and the analysis of the qualitative information provided by the interviewed participants (n = 13). This section first addresses the main themes in the broad scenario of datafication identified by the CSOs. The second part discusses the findings concerning resistance practices and how they are understood and enacted in a datafied scenario. Finally, the section concludes with an analysis of their perceptions about imbalances and agency in the global context of datafication.

A datafied society: The concerns of CSOs in the region

Although the concept of "datafication" is understood by the CSOs but not expressed in its Spanish or Portuguese equivalent term, there is an on-the-ground approach that denounces the appropriation of social, political, cultural, economic, and private spheres by technology and data-based applications. This perception of the role of data and networked technologies is not unique to the region. However, part of a perspective of CSOs globally, mainly after Snowden, reflected the threats of surveillance and how to resist and change this pervasive practice (Pohle & Van Audenhove, 2017).

Data and "techno-solutionism" —as expressed by one informant is perceived as a short-cut for some governments' developmental and public policy objectives,

but without attacking endemic problems in the region, such as corruption (personal communication, September 2020).

For example, part of the work carried out by Ciudadanía Inteligente, especially the open data principles embraced by many organisations, is perceived as tools for establishing democratic governments in the region, promoting more accountability, transparency, and citizen participation, and denouncing corruption.

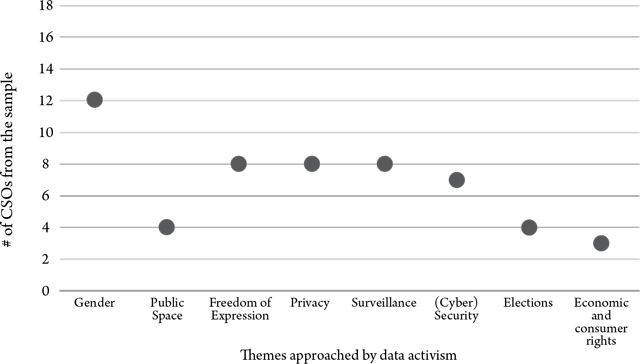

Based on the studies available online and conducted by these organisations, the problems of datafication are noted in the following issues in order of frequency: gender, privacy, surveillance, freedom of expression, (cyber)security, elections, public space, and economic and consumer rights (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Issues approached by the studied CSOs

Source: Own elaboration based on the CSO sample.

Bound by the research scope, we will limit the analysis to two of the most salient: gender and privacy. Gender is the most prevalent topic among the CSO sample, but their approaches have significant variations. In the annual report prepared by Derechos Digitales (2017), "Latin America in a Glimpse," seven strategic approaches5 were identified on "gender, feminism, and the Internet." These approaches combine reactive and proactive actions in 27 initiatives led by CSOs in the region. The diversity of approaches and growing numbers of initiatives highlight the tensions surrounding datafication in a physical context where violence, sexism, and inequality are still rampant but increasingly resisted.

This year we will launch a research project into the non-consensual dissemination of intimate images; we will analyse the judges who led gender issues and how lawyers use this legal concept to report complaints (personal communication, September 2020).

Most of the surveyed CSOs were undertaking or had undertaken initiatives that addressed online gender violence and platform discrimination against women and LGBTQI. Although the initial CSO's focus included denouncing platforms' policies on content moderation and removal and a lack of clarity and accountability mechanisms to redress the issue, it now encompasses the underlying architecture of the algorithms that inhibit or foster automated decisions based on circulating data, an emergence of proactive data activism —hacking strategies, appropriation (Feenberg, 1999) through education, and coding skills—, and alliances between organisations and developers.

For instance, Hiperderecho from Peru has produced a report curating the legal tools for women facing online gender violence (Hiperderecho, 2020); Coding Rights has produced many reports on the algorithmic bias that violates gender and reproductive rights and attacks sexual and ethnic/racial diversity (Peña & Varon, 2019); Sulá Batsu in its "Programa TICas" has recently developed a community-based platform by Cabécar women in Costa Rica,6 and Maria Lab, quoting Paulo Freire, develop their community networks and feminist infrastructures as instruments of struggle.7 This work includes all modes of resistance: the struggle against surveillance, normative change, and citizen-oriented initiatives focusing on education and knowledge of the systems and the technologies to promote proactive data activism.

Privacy promotion through data protection legislation advocacy emerges as a second salient theme that has become a powerful instrument for Latin American CSOs, particularly those with a long path in human rights. It is concentrated in the Al Sur consortium composed of eleven organisations, which will be elaborated on later (Al Sur, 2020). Although most Latin America and the Caribbean countries have national data protection laws (16), half a dozen are discussing a bill, and eleven do not yet have comprehensive national frameworks (ECLAC and Internet and Jurisdiction, 2020). While many have these instruments, there are numerous problems with their implementation and enforcement, more so in the pandemic context and the enforced surveillance practices.

The pandemic has accelerated some notions about how paradigms can change and how people and decision-makers in the region stand up to the use of data (personal communication, September 2020).

The work surrounding data protection and data privacy is not univocally approached. On the one hand, the issue is open to perspectives that invoke legal but also technical tools. On the other, strategies and tactics for other issues are both reactive in terms of organising defensive approaches particularly prominent in CSO's activities during the early months of the pandemic, and proactive, including human rights promotion embedding privacy in technology formulation and development. The preceding is noticeable in the approaches ofFundación Karisma K+ Lab, which is "the first digital security and privacy laboratory in Colombia designed by and for civil society" (Fundación Karisma, 2018); or report-based strategies such as TE-DIC's (TEDIC, 2020), which go beyond denunciation to promote educational material; or policy-oriented strategies such as ADC's (ADC, 2020).

While data protection is a necessary instrument that can be invoked in the resistance towards datafication, it is sensed as insufficient. Data protection is a tool that may have more legitimacy in the context of more stable and representative democracies since the State is the actor that must enforce it.8 In Latin America, this instrument is vital, but by no means sufficient, particularly with the levels of distrust towards governments in many national contexts:

This tension and mistrust around the States' role in data protection play a significant role in the weight of resistance to deploy powerful strategies to change regulatory frameworks that can force companies to follow international data protection guidelines nationwide. There is distrust of governments as violators of rights, but they must be the ones that protect our rights, added to a complicated relationship with the same international companies that violate users' rights with their data (personal communication, September 2020).

This statement underscores how civil society configurations in Latin America have been noted to be, at the same time, points of resistance and hegemonic collusion (Fischer, 2007) and the challenges emerging from a shifting complex scenario of funding sources and donor agendas.

Privacy is also an issue bound by cultural, social, and educational opportunities and is unequally deemed a problem by average citizens in the region; hence, the considerable efforts made by organisations around this issue. Although some authors have pointed out that digital rights advocacy is limited to a specialised group of experts that discuss data protection, which can be seen as a weakness in enhancing data justice endeavours (Hintz et al., 2019), CSOs are not disconnected from broader needs to raise awareness among citizens of the necessary skills to address their data protection rights. Without this knowledge, no denunciation or resistance is possible.

The average Latin American does not read privacy policies and accepts everything. They do not seek to get information, nor are they informed by leaders about their rights. They do not know that their personal data is quantified and that today it is more important than oil (personal communication, September 2020).

The unequal treatment of data by jurisdiction based on data protection frameworks is also considered a differential characteristic that underlies approaches to data use:

In parallel, a wave of artificial intelligence proposes to solve all social problems. With this vision, these companies from the North come to test different algorithms that they would not in European countries where data protection is much more robust (personal communication, September 2020).

European companies are not part of the so-called companies of the Global North as claimed by ADC since the data protection framework — General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)— would not allow these companies to use this data in the same way.

Expanding resistance and data activism

This subsection addresses the second objective of identifying resistance practices adopted by the CSOs. The study of these organisations reveals that research is a significant part of their advocacy efforts, underscoring the prevalence of Pasquali's research-denunciation approach and the process of epistemic validation. The language that these organisations use to describe problems surrounding big data is part of the assemblages being reconstructed by these organisations (Milan & van der Velden, 2016). An example is Fundación Karisma's "Research and Active Participation" approach based on Freire, supporting "the sustainable use of technologies according to the communities' context, interests, and needs" (Fundación Karisma, 2021).

Using the thematic instrument designed for document analysis was built on a) a proactive/reactive categorisation proposed by Milan and Gutiérrez (2015) and b) Hintz et al.'s (2019) classification of resistance practices —technological pursuits aimed at self-protection from surveillance, lobbying, and data collection and use for advocacy—, the analysis suggests that CSOs display a variety of data activism strategies. Over 70 % can be considered proactive data activism practices when compared to reactive ones. Nearly half (44 %) of their approaches evince resistance practices to surveillance; however, more than 70 % of their strategies are related to lobbying and data collection for advocacy. There is a prevalence in the resistance of these organisations to implement more traditional CSO strategies based on lobbying to promote policy and regulatory changes and subvert the mainstream uses of technologies for market services to address social and public interest initiatives.

We identified three additional modes of resistance using the inductive approach to the thematic analysis of CSOs practices in their publications. The first is digital activism through hashtivism. For example, three Argentine CSOs (Fundación Vía Libre, ADC, Access Now) conducted an online campaign against facial recognition on Twitter, #ConMiCaraNo and #NoAlReconocimiento, to oppose the implementation of this technology in Buenos Aires

A second practice is connected to educational approaches in non-formal settings, which adopt in part Freire's legacy of popular education to create settings for participation, denunciation, and resistance. Examples abound, from gamification,9 to hackathons,10 to more traditional approaches such as webinars, workshops, and reports.

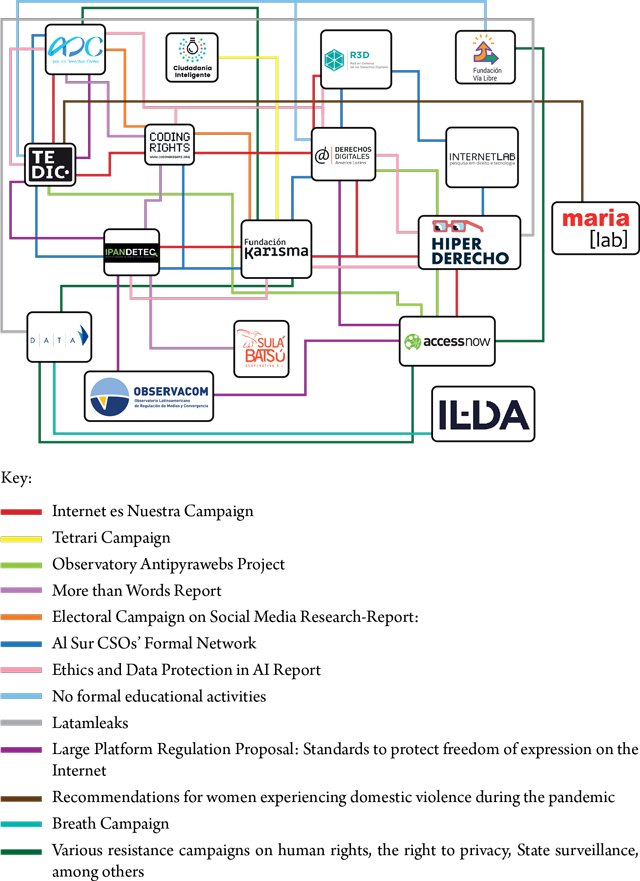

Finally, the third practice is the proactive development of CSO networks with a different geographic and thematic scope and organisational structures. The proactive data activism strategies mentioned earlier are defined by these networks to strengthen and improve CSOs' chance of success in their activism. Figure 2 depicts seven initiatives/campaigns identified, the largest one covering as many as nine organisations (e.g., "Internet es Nuestra").

Figure 2. CSO networks as proactive data activism strategies.

Source: Own elaboration

While it is out of the scope of this paper to analyse these campaigns, their study has enabled the distinction of three types of networked practices by these organisations. The first type is the most formal and comprehensive structure of an institutionalised network. This is the case of Al Sur, a consortium of digital rights non-governmental organisations (NGOs) with a formal secretariat and coordinated agenda for civil society and academia for jointly "strengthening human rights in the regional digital environment" (Al Sur, 2021).

We perceive that each of us, on our own, are not persuasive enough to draw public attention in these discussions (personal communication, September 2020).

This approach is in line with the renewed appraisal of issue networks and CSOs in the context of ICT use (Marres, 2013). This institutionalised network usually works on an issue basis and strategises and acts in more than one country. This method is also valued as a sustainability strategy that allows for coordination at the regional and global levels. Another example of an institutionalised network operating globally but with strong participation of CSOs in the Latin American region, including many in the sample, is the "A+ Alliance: Alliance for Inclusive Algorithms," which aims to address biases in AI and de-construct algorithms from gender and feminist perspectives.11

The second type of network practice is the local ad-hoc network for country-oriented issues. For instance, six organisations involved in defending human rights in Brazil filed legal action in February 2020 demanding transparent information on the use, processing, and storage of biometric data and security measures to guarantee the privacy of the millions of metro users in Sao Paulo (Venturini, 2020). Similar strategies have been seen in practically all countries. These resistance practices tend to be reactive and defensive, usually against the inclusion of technology or bills/legal reforms that violate human rights, and act at the intersection of connective and collective action approaches (see Bennett & Segerberg, 2012).

The third type of network is the regional ad-hoc network that convenes partners across Latin America to impact the regional policy agenda. An example of this network approach is Brazil, where a coalition of organisations and initiatives are working on regionally extended facial recognition. Furthermore, Buenos Aires was one of the first cities to deploy this technology in the region. In response, CSOs based in Argentina (ADC, Fundación Via Libre, Access Now), Chile (Derechos Digitales, 2019), Colombia (Fundación Karisma), and Uruguay (DATA.uy) became involved in a resistance movement against the deployment of facial recognition technologies and State surveillance to defend privacy and promote transparency on such a sensitive public policy measure (Access Now, 2018).

By the time they want to bring something to the southern hemisphere already tested in the North, some resistance has been put up. Basically, we are not usually the guinea pigs. For example, with facial recognition and its arrival in Argentina, the technology would have been much more widespread if there had not been this collective resistance (personal communication, September 2020).

The resistance practices included denouncing policy and regulatory frameworks on the grounds of violating human rights for implementing datafication. While resistance has been mounted, public authorities in the region are still calling on using these technologies, many of which are from Chinese vendors.

The development of civic technology among different CSOs is another example of proactive practices of resistance through network action. As a local network action, it is sometimes part of an alternative model of communication (Freire, 1994), in which the collective reflection on technology, its multilevel impacts and uses are part of a citizen empowerment process:

We develop technology according to our needs. Moreover, this development is achieved by, and with, those who will use these technologies. This construction is a collective project (...) We work for a communitarian data model, oriented at developing and creating communitarian infrastructure for data access, storage, and management, without relying on intermediaries (personal communication, September 2020).

This idea of creating a new alternative model of communication comes with the notion of assuming an active role in developing the region and is also part of another resistance practice that goes beyond research-denunciation:

Proposing, being proactive, is at this point the best way to resist (personal communication, September 2020).

Latin American civil society perceptions on datafication in the global context vis-a-vis the regional context

This last subsection examines the CSOs' perceptions of the asymmetrical capacity of different actors in the region to address datafication, particularly in the context of what has been theorised and considered data colonialism (Couldry & Mejias, 2019), which provokes different data activism practices. Regarding datafication, the distinction between intra- and extra-regional asymmetries involves the institutional capacity of actors —including governments, businesses and CSOs— to access and use data.

Some asymmetries perceived within different countries' scale, population, and market development elicit different responses from the CSOs. While the region has not produced global industry players, some corporations —for example, the digital retailer Mercado Libre— symbolise data prowess and platformisation practices coming from Latin America (Guru-murthy et al., 2018). From a civil society perspective, these differences result in different approaches and types of struggles in the national contexts, which also must address the emergence of local companies with the same extractive models as those from the West.

I mostly see data colonialism related to technological determinism and technological positivism, maximising data for innovation without considering the potential harms (personal communication, September 2020).

The sample of organisations selected reflects an ample breadth of epistemic positions and data activism practices. These intra-regional asymmetries influence data activism and even their perception of the scope and nature of the problem.

I believe that we have rarely seen such regional fragmentation in many political aspects, and this issue is no exception, both at the level of public administration and public policy (personal communication, September 2020).

Although collaboration is a means of resistance, and the networked approaches analysed in the previous section are an example, there is no coherent and shared perception of the role of technologies and datafication processes in the systemic political processes in the region, which underscores the epistemic challenges to grasp the problem and the practices that should follow. Nonetheless, CSOs perceive asymmetrical capacities between governments and global tech corporations:

The capacity that States have for measuring and quantifying is unequal if we compare it with private companies' capacity. Furthermore, this is a problem with public technology policies and traditionally unfair situations, such as land disputes in Colombia (personal communication, September 2020)

This difficulty governments have in producing and working with their own local data has been identified, particularly in the interviews, as a tremendous disadvantage in the region. This theme has been explored by many campaigns and efforts, mainly through reactive data activism approaches based on denunciation.

Latin America is very passive about producing information and feeding large volumes of data to serve its own interests. Instead, it employs different types of automated systems by large corporations, which then use it to improve the technologies they sell later (personal communication, September 2020).

Not all players have the same capacity to process and extract value as the tech giants. An example mentioned by interviewees is the reliance on companies such as Google and Apple with their API for COVID-19 contact tracing, posing significant threats for democratising data-driven technologies and appropriation by growing regional actors, including CSOs.

For us, there is a problem with data centralisation, storage, and management, and the capacity of our governments to produce technologies and make public policies on the issue. Most times, our country privatises databases and technological solutions relying on the global order, which is part of the business model applied in all our countries (personal communication, September 2020).

The processes of datafication include a complex mesh of actors in global digital value chains. While more profit is extracted from data in developed economies, interviewees emphasised the importance of Latin American citizens' data that feeds into global platforms:

It is very perverse because our data is favouring large global companies. It is subtle, few people realise it, but benefits monopolies; it is very difficult for alternative companies to incorporate other more respectful approaches in their artificial intelligence tools (personal communication, September 2020).

CSOs do not react and interpret the context as that of asymmetrical imposition, but they have their views about the role of local firms in how data extraction and monopolies are developed in the absence of more complex and robust local data supply chains:

I believe we are immersed in a colonialist data paradigm, but with some caveats. The absence of ubiquitous digitisation in Latin America and a lack of data brokers in the region puts a curb on that (personal communication, September 2020).

The absence of public interest initiatives related to data provides an opportunity for CSO data activism. Re-examining the purposes of technology is a central piece of the epistemological exercise resistance initiatives embark on to question extractive practices.

Concluding remarks

Latin America is a region where communicative expression is an intrinsic part of the regional identity (Crovi Druetta, 2004) and relevant cultural and political resistance practices. The struggle against the marginalisation of non-hegemonic, non-Western, anti-capitalist, and subaltern voices has been a cornerstone since the origins of the Latin American School of Communication. We claim that this awareness of "Latin Americanness" (Barranquero, 2011) present in the continent's historical contexts evinces both transformations and continuities in the context of datafication concerning past mass communication premises based on 20th-century broadcasting technologies.

Participatory action research allows modulating and connecting resistance knowledge and power in the region (Vega-Casanova, 2021). Without knowledge, resistance and denunciation are not possible in a datafied scenario, reasserting the legacies of Pasquali and Freire. The existing categories and dimensions of resistance in the literature do not capture the vast range of repertoires identified that go beyond the research-denunciation approach to form a triad of research-denunciation-action on collective grounds.

The consolidation of network cooperation by CSOs working on the digital human rights front identified by this research has transformed resistance practices, particularly strengthening gender issues and privacy rights as central pieces of their programs. These networked forms of resistance addressing a more comprehensive human rights agenda since the turn of the 21st century in the region (Fontana & Grugel, 2017) consolidate Pasquali's and Freire's research-denunciation and theory-praxis with new instruments for participatory action research that go beyond digital citizenship resistance practices found in the literature.

To challenge the frailty of isolation and lack of resources, CSOs in the region embrace data activism both proactively and reactively to push for changes in the regulatory frameworks through lobbying, campaigns, and capacity building. They also deploy civic-tech responses and alternative uses of data (Hintz et al., 2019), in line with other resistance categories. We also find that they operate a networked approach to become more persuasive and capable of introducing systemic changes and engaging in capacity building and awareness campaigns for citizens. Without these, the claims of civil society around datafication processes would still be part of the elite discussion, with a limited impact on the alternative forms of integration of data and technology in a materially and epistemically diverse region.

The heuristic categorisation of proactive and reactive data activism (Gutiérrez & Milan, 2017; Milan & Gutiérrez, 2015) has delimited and defined CSO resistance practices in this region with the concept of agency —knowledge and action— as a crucial dimension. The proactive vs reactive continuum also provides a valuable conceptual bridge with the more abstract theoretical formulations of Pasquali and Freire. While both address resistance and ultimately aim at social change by democratising access, means, and uses of technology, reactive and proactive data activism are more inductive constructs valuable for analytical and definitional approaches towards an issue that is still being shaped and contested.

The data activism we found seeks to cross borders and has analogies with the 1970s utopian formulations in search of social transformation, a context in which the Latin American School of Communication thrived. This work can be further expanded through a protracted historical approach to map more clearly the resistance practices in a datafied context that are relevant to those that reflect CSOs' regional patterns and ideals of emancipation (Peet & Watts, 1996).

Our research also contributes to the discussion on assemblages in global governance and the role of civil society, which has been side-lined in the configuration of technopolitical dynamics (Mayer et al., 2014). These findings contribute to the growing literature on how knowledge is constructed, shaped, and shared by civil society around a policy issue that is blurring and re-arranging boundaries and past track records of advocacy for human rights, media democratisation, and sustainable development facing datafication.

One such change is the notion of data colonialism, which is both resisted and accepted as a factor of fluctuating power, control, and capacity between regions —with a focus on the role of Latin America— in our study. While the research did not find unequivocal support to adhere to a matrix of domination in colonial terms, it helped reinforce the broader "technopolitical" discussions that should be addressed when making comprehensive data policies. This matter entails further research on how datafication works, its sources, drivers, and the challenges around fostering social justice and inclusive democracies.

Freire's approach to liberation pedagogy (2004) and its emphasis on the agency of individuals and communities as the revitalising architects of the theory-praxis unit for social change (Milan & Treré, 2021) are fundamental to the notions of digital activism in the region. For instance, #tusderechoseninternet, #ConMicaraNo, #botsAmigues, among other hash-tivism movements, are related to the affordances of social media and the resonance with broader movements emanating from the region that have achieved global visibility. The movement #Unvioladorenmicamino from the Chilean performance group Las Tesis is aligned with the basis of the CSO's online gender rights approaches. However, there is still much more work to be accomplished in tracing similarities and differences between social movements in the region, coordinated efforts from organised civil society, and the connective/collective action discussion.

We found implicit tensions and one explicit mention from the CSO sample about how their working agenda and thematic approach are funded and shaped by donors. We were unable to address this issue in the research, which deserve deep analysis to identify mechanisms and formal or informal barriers to how the problems surrounding datafication are moulded and resistance occurs (or not).

Finally, data activism in the context of a pandemic needs to be explored (Milan et al., 2021), as the subject increasingly becomes an instrument and circumstance for resistance, and different nuances and meanings attached to these practices arise over time.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank their interviewees, who, in times of the COVID-19 pandemic, contributed to this work with their comments. We also thank María Belén Chilano and Ivana Guerrero for their research assistance.

Notes

1 Some examples of the former include the formation of the New World Information and Communication Order (NWICO) (1980) and the World Summit on the Information Society (WSIS) process (2003-2005). At the national level, initiatives flourished to promote principles, coalitions, and forums for media democratization (Argentina, Brazil, Ecuador, Uruguay) (Segura, 2014).

2 Pasquali introduced the notion of Políticas Nacionales de Comunicación in 1970 to contest the existing communication order based on public service broadcasting principles (Olmedo, 2011).

3 Some examples include the Femicidios crowdsourced mapping initiative created in 2016 (https://feminicidiosmx.crowdmap.com/) to map femicides in Mexico and CIUDATA, which using several data sources from apps, including OpenStreetMap, alerts women and vulnerable communities about high violence areas in urban settings (https://ci-udatamx.wordpress.com/2017/07/14/callesvioletas/). In Nicaragua, femicide mapping with Open Street Map and Carto apps run by all-female team of volunteers called Geochicas chart unsafe places for women (https://seleney-ang.carto.com/builder/14f3a6a1-03ce-47df-b3e7-bf1bd7b36298/embed).

4 Responses and quotes have been translated from Spanish by the authors.

5 Technological autonomy: feminist infrastructure; data, codes, circuits: women working in technology; Internet for human rights support, access, and defence; feminist pedagogies: learning and doing together; counterinformation, visibility and narrating ourselves; knitting networks: encounters with women and technology; research for denunciation, comprehension, claiming, and strengthening (Derechos Digitales, 2017).

6 “Programa TICas” (https://www.sulabatsu.com/ticas/; Okamasüei (White Man’s Technology in Cabécar) (https://programafrida.net/en/archivos/project/okamasuei )

7 More systematised knowledge is indispensable to popular struggle [...] but this knowledge must follow the paths of practice. (Freire, 2014)

8 The impact of datafication on elections and democratic processes, as well as on other human rights (https://adc.org. ar/informes/democracia-segmentada/) are also part of this debate.

9 ILDA trivia on femicides in the region (https://datasketch.github.io/ilda-trivia/)

10 IPADENTEC on fostering open data culture (https://www.ipandetec.org/2020/05/26/datos-abiertos-femenino/=)

11 https://aplusalliance.org/. (One of the co-authors is involved in this initiative).

References

Abregú, M. (2008). Derechos Humanos para todos: de la lucha contra el autoritarismo a la construcción de una democracia inclusiva - una mirada desde la Región Andina y el Cono Sur. Revista Internacional de Direitos Humanos, 5(8), 06-41. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1806-64452008000100002

Access Now. (2018). Facial recognition on trial: emotion and gender "detection" under scrutiny in a court case in Brazil. https://www.accessnow.org/facial-recognition-on-trial-emotion-and-gender-detection-under-scrutiny-in-a-court-case-in-brazil/

ADC. (2020). Cómo implementar la debida diligencia en derechos humanos en el desarrollo de tecnología. https://adc.org.ar/informes/como-implementar-la-debida-diligencia-en-derechos-humanos-en-el-desarrollo-de-tecnologia/

Al Sur. (2020). Quienes somos. https://www.alsur.lat/quienes-somos

Al Sur. (2021). What we do. https://www.alsur.lat/en/what-we-do

Amado, A., & Tarullo, R. (2019). Journalism and Civil Society: Key to Data Journalism in Argentina. In B. Mutsvairo, S. Bebawi, & E. Borges-Rey (Eds.), Data Journalism in the Global South (pp. 1-26). Palgrave Macmillan.

Baack, S. (2015). Datafication and empowerment: How the open data movement re-articulates notions of democracy, participation, and journalism. Big Data & Society, 2(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951715594634

Bambozzi, E. (2013). Debates Pedagógicos Contemporáneos en perspectiva latinoamericana: construyendo una pedagogía latinoamericana de la comunicación. VIEncuentro Panamericano de Comunicación, Escuela de Ciencias de la Información, Universidad Nacional de Córdoba. https://www.publicacioncompanam2013.eci.unc.edu.ar/files/companam/ponencias/Comunicaci%C3%B3n%20y%20Educaci%C3%B3n/Comunica_educacion_Bambozzi.pdf

Barranquero, A. (2011). Latinoamericanizar los estudios de comunicación. De la dialéctica centro-periferia al diálogo interregional. Razón y Palabra, 75.

Barranquero, A. & Sáez-Baeza, C. (2012). Teoría crítica de la comunicación alternativa para el cambio social: el legado de Paulo Freire y Antonio Gramsci en el diálogo norte-sur. Razón y Palabra, 16(180), 40-52.

Becerra, M. (2014). Medios de comunicación: América Latina a contramano. Revista Nueva Sociedad, (249), 42-55.

Bennett, W. & Segerberg, A. (2012). The logic of connective action. Information, Communication & Society, 739-768. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2012.670661

Beraldo, D. & Milan, S. (2019). From data politics to the contentious politics of data. Big Data & Society, 6(2) https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951719885967

Boellstorff, T. (2013). Making big data, in theory. First Monday, 18(10). https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v18i10.4869

Braman, S. (2006). Change of State: Information, Policy, and Power. The MIT Press.

Calo, R. (2017). Artificial Intelligence Policy: A Primer and Roadmap. https://lawreview.law.ucdavis.edu/issues/51/2/Symposium/51-2_Calo.pdf

Castells, M. (2009). Comunicación y poder. Alianza.

Chenou, J. M. & Cepeda-Másmela, C. (2019). #NiUnaMenos: Data Activism from the Global South. Television & New Media, 20(4), 396-411. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476419828995

Ciuriak, D. (2018). Frameworks for Data Governance and the Implications for Sustainable Development in the Global South. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3266113

Costa, A. & Otre, M. (2019). O protagonismo de Antonio Pasquali na pesquisa-denuncia e sua influencia sobre a Escola Latino-americana de Comunicação (Personaje). Chasqui Revista Latinoamericana de Comunicación. Libertad de expresión, 21-24. ISSN: 1390-1079.

Couldry, N. & Mejias, U. A. (2019). Data Colonialism: Rethinking Big Data's Relation to the Contemporary Subject. Television and New Media, 20(4), 336-349. http://doi.org/10.1177/1527476418796632

Crawford, K. & Joler, V. (2018). Anatomy of an AI System: The Amazon Echo as an anatomical map of human labor, data and planetary resources. https://anatomyof.ai/

Crovi Druetta, D. (2004). Aportes latinoamericanos a los estudios de comunicación. In Martell Gámez, L. (coord.), Hacia la construcción de una ciencia de la comunicación en México. Ejercicio reflexivo 1979-2004 (pp. 83-99). Asociación Mexicana de Investigadores de la Comunicación.

de-Lima-Santos, M. & Mesquita, L. (2021). Data Journalism in favela: Made by, for, and about Forgotten and Marginalized Communities. Journalism Practice, 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2021.1922301

De Nardis, L. (2020). The Internet in Everything: Freedom and Security in a World with No Off Switch. Yale University Press.

Derechos Digitales. (2017). Latin America in a Glimpse. Gender, Feminism and the Internet in Latin America. https://www.derechosdigitales.org/wp-content/uploads/GlImpse2017_eng.pdf

Derechos Digitales. (2019). La sociedad exige explicaciones sobre la implementación de sistemas de reconocimiento facial en América Latina. https://www.derechosdigitales.org/14207/la-sociedad-exige-explicaciones-sobre-la-implementacion-de-sistemas-de-reconocimiento-facial-en-america-latina/

Díaz-Bravo, L., Torruco-García, U., Martínez-Hernández, M. & Varela-Ruiz, M. (2013). La entrevista, recurso flexible y dinámico. Investigación en Educación Médica, 2, 162-167. https://doi.org/10.3167/sa.2007.510201

Dutta-Bergman, M. J. (2004). Complementarity in consumption of news types across traditional and new media. Journal of broadcasting & electronic media, 48(1), 41-60. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15506878jobem4801_3

ECLAC, & Internet and Jurisdiction. (2020). Regional Status Report 2020 (LC/TS.2020/141).

Faraj, S., & Azad, B. (2012). The Materiality of Technology: An Affordance Perspective. In P. M. Leonardi, B. A. Nardi, & J. Kalliniko (Eds). Materiality and organizing: Social interaction in a technological world. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199664054.001.0001

Feenberg, A. (1999). Reflections on the distance learning controversy. Canadian Journal of Communication, 24, 337-348. https://doi.org/10.22230/cjc.1999v24n3a1110

Fischer, E. (2007). INTRODUCTION: Indigenous Peoples, Neo-liberal Regimes, and Varieties of Civil Society in Latin America. Social Analysis, 1-18. https://doi.org/10.3167/sa.2007.510201

Fontana, L. B., & Grugel, J. (2017). La nueva agenda de derechos humanos en América Latina: ¿Qué derechos cuentan? Open Democracy. https://www.opendemocracy.net/es/la-nueva-agenda-de-derechos-humanos-en-am-rica-latin/

Freire, P. (1975). Pedagogía del oprimido. Siglo XXI.

Freire, P. (1993). Política eEducação: Ensaios. Cortez.

Freire, P. (1994). Educación y participación comunitaria. Nuevas perspectivas críticas en educación. Paidós.

Freire, P. (2014). Educação como prática da liberdade. Paz e Terra.

Fundación Karisma. (2018). K+ LAB: Seguridad Digital. https://web.karisma.org.co/pagina-principal/laboratorios/klab/

Fundación Karisma. (2021). K- Apropiación Tecnológica. https://web.karisma.org.co/k-apropiacion-tecnologica/

García Canclini, N. (2004). Diferentes, desiguales y desconectados. Mapas de la interculturalidad. Gedisa.

García Canclini, N. (2020). Ciudadanos reemplazados por algoritmos. Bielefeld University Press. https://doi.org/10.14361/9783839448915

Gaver, W. (1991, April). Technology affordances. CHI '91: Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 79-84). https://doi.org/10.1145/108844.108856

Gitelman, L. (2013). "Raw Data" Is an Oxymoron. The Mit Press.

Gobbi, M. (2004). La Escuela Latinoamericana de la Comunicación: del hibridismo metodológico al compromiso ético-político. Mediaciones, 2(3), 55-69. https://doi.org/10.26620/uniminuto.mediaciones.2.3.2004.55-69

Hernández Sampieri, R., Fernández Collado, C., & Baptista Lucio, P. (2014). Metodología de la Investigación. McGraw-Hill.

Gurumurthy, A., Bharthur, D., & Chami, N. (2018). Policies for the Platform Economy: Current Trends and Future Directions. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.30219.72480

Gutiérrez, M. (2018a). Data Activism and Social Change. Palgrave Pivot. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-78319-2

Gutiérrez, M. (2018b). Maputopias: Cartographies ofknowledge, communication and action in the big data society - The cases of Ushahidi and InfoAmazonia. GeoJournal, 84(1), 101-120. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-018-9853-8

Gutiérrez, M., & Milan, S. (2017). Technopolitics in the Age of Big Data: The Rise of Proactive Data Activism in Latin America in Networks, Movements and Technopolitics in Latin America: critical analysis and current challenges. In F. Sierra Caballero and T. Gravante (Eds.), Networks, Movements and Technopolitics in Latin America (pp. 95-109). Palgrave IAMCR Book Series. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-65560-4_5

Hintz, A., Dencik, L., & Wahl-Jorgensen, K. (2019). Digital Citizenship in a Datafied Society. Polity Press.

Hiperederecho. (2020). Después de la ley. Buscando justicia de género para mujeres y personas LGBTQ+ que enfrentan violencia de género en línea en el Perú. Informe #2. https://hiperderecho.org/wp-content/up-loads/2020/12/Informe-2_Despue%CC%81s-de-la-ley.pdf

Leurdijk, A. (2007). Public Service Media Dilemmas and Regulation in a Converging Media Landscape. In G. Ferrell Lowe & J. Bardoel (Eds.), From Public Service Broadcasting to Public Service Media. RIPE@2007. Gõteborg University.

León Duarte, G. (2001). Teorías e Investigación de la Comunicación en América Latina. Situación Actual. ÁMBITOS.

Majchrzak, A., & Markus, L. (2014). Methods for Policy Research: Taking Socially Responsible Action. Sage.

Marques de Melo, J. (1998). Teoría de la comunicación: Los paradigmas latino-americanos. Voces.

Marres, N. (2013). Net-Work Is Format Work: Issue Networks and the Sites of Civil Society Politics. In Reformatting Politics (pp. 33-48). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203957066-8

Mayer, M., Carpes, M., & Knoblich, R. (2014). The Global Politics of Science and Technology: An Introduction. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-55007-2_1

Meraz, S. (2011). The fight for 'how to think': Traditional media, social networks, and issue interpretation. Journalism, 12(1), 107-127. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884910385193

Milan, S. (2015). When Algorithms Shape Collective Action: Social Media and the Dynamics of Cloud Protesting. Social Media + Society,1 (2). https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305115622481

Milan, S. (2018). Political agency, digital traces and bottom-up data practices. International Journal of Communication, 12, 507-527. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/6709/2251

Milan, S., & Gutiérrez, M. (2015). Medios ciudadanos y big data: La emergencia del activismo de datos. Mediaciones, 11(14), 10-26. https://doi.org/10.26620/uniminuto.mediaciones.11.14.2015.10-26

Milan, S., & Gutiérrez, M. (2017). Technopolitics in the Age of Big Data. In F. Sierra Caballero & T. Gravante (Eds.), Networks, Movements and Technopolitics in Latin America: Critical Analysis and Current Challenges (pp. 95-109). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-65560-4_5

Milan, S., & Treré, E. (2019). Big Data from the South(s): Beyond Data Universalism. Television and New Media, 20(4), 319-335. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476419837739

Milan, S., & Treré, E. (2021). Latin American Visions for a Digital New Deal: Towards Buen Vivir with Data. In S. Sarkar & A. Korjam (Eds.), A Digital New Deal: Visions of Justice in a Post-Covid World (pp. 100-112). Net Coalition and IT for Change.

Milan, S., Treré, E., & Maseiro, S. (2020). COVID-19 from the Margins. Pandemic Invisibilities, Policies and Resistance in the Datafied Society. Institute of Network Cultures.

Milan, S., & van der Velden, L. (2016). The alternative epistemologies of data activism. Digital Culture & Society, 2(2), 57-74. https://doi.org/10.14361/dcs-2016-0205

Montoya-Londoño, C. (2010). Alianzas entre Medios de Comunicación y Organizaciones de la Sociedad Civil: Balances y propuestas para fortalecer la Democracia y los Derechos Humanos.

Olmedo, S. (2011). Comprender la comunicación, de Antonio Pasquali. Razón y palabra, 75, 1-31.

Ozonas, L., & Perez, A. (2005). La entrevista semiestructurada. Notas sobre una practica metodologica desde una perspectiva de género. Revista de Estudios de La Mujer. La Aljaba.

Pasquali, A. (1998). Bienvenido Global Village. Monte Ávila.

Pasquali, A. (2007). Comprender la comunicación (revised edition). Gedisa.

Peet, R. & Watts, M. (1996). Liberation Ecologies. Environment, development and social movements. Routledge.

Peña, P., & Varon, J. (2019). Decolonising AI: A transfeminist approach to data and social justice. In GISWATCH 2019, Artificial Intelligence: Human Rights, Social Justice and Development (pp. 317-329). APC. https://giswatch.org/sites/default/files/gisw2019_artificial_intelligence.pdf

Pohle, J., & Audenhove, L. V. (2017). Post-Snowden Internet Policy: Between Public Outrage, Resistance and Policy Change. Media and Communication, 5(1), 1-6. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v5i1.932

Ricaurte, P. (2019). Data Epistemologies, The Coloniality of Power, and Resistance. Television and New Media, 20(4), 350-365. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476419831640

Sánchez Navarte, R. (2014). Arrojados hacia lo concreto. Pasquali y Freire en las tramas culturales intelectuales de los años sesenta. Questión, (1), 42.

Segura, M. S. (2014). La sociedad civil y la democratización de las comunicaciones en Latinoamérica. Íconos-Revista de Ciencias Sociales, (49), 65-80. https://doi.org/10.17141/iconos.49.2014.1272

Siles, I., Espinoza, J., & Méndez, A. (2019). La investigación sobre tecnología de comunicación en América Latina: Un análisis crítico de la literatura (2005-2015). Palabra Clave, 22(1), 1-29. https://doi.org/10.5294/pacla.2019.22.1.2

Srnicek, N. (2017). Platform Capitalism. Polity Press.

Sunkel, G. (2006). El consumo cultural en América Latina. Convenio Andrés Bello.

Tarullo, R., & Frezzotti, Y. (2020). Sobre la participación digital de la juventud universitaria en Argentina: el hashtivismo y el emojivismo como estrategias de compromiso cívico. Austral Comunicación, 9(2), 609-634. https://doi.org/10.26422/aucom.2020.0902.tar

Tarullo, R., & García, M. (2020). Hashtivismo feminista en Instagram: #NiñasNoMadres de @actrices.argentinas. Dígitos. Revista de Comunicación Digital, 6, 31-54. https://doi.org/10.7203/rd.v1i6.172

TEDIC. (2020). Privacidad y Datos Personales. https://www.tedic.org/privacidad-y-datos-personales/

Treré, E. (2016). Distorsiones tecnopolíticas: represión y resistencia algorítmica del activismo ciudadano en la era del 'big data,' Trípodos, (39) 35-51.

Tufekci, Z. (2014). Engineering the Public: Internet, Surveillance and Computational Politics. First Monday, 19(7). https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v19i7.4901

Valencia Rincón,J. (2012). Mediaciones, comunicación y colonialidad: encuentros y desencuentros de los estudios culturales y la comunicación en Latinoamérica. Signo y Pensamiento, 31(60), 156-165. https://revistas.javeriana.edu.co/index.php/signoypensamiento/article/view/2417

Valles, M. (1999). Entrevistas cualitativas. Centro de Investigaciones Metodológicas.

Vega-Casanova, J. (2021). Disenchantment as a Path Toward Autonomy: Orlando Fals Borda, Participatory Action Research, Communication and Social Change. In A. C. Suzina (Ed.), The Evolution of Popular Communication in Latin America (pp. 109-128). Palgrave Studies in Communication for Social Change.

Venturini, J. (2020). Los problemas de nunca acabar, Latin America in a glimpse. APC. https://www.apc.org/es/pubs/latin-america-glimpse-genero-feminismo-e-internet-en-america-latina

Zuboff, S. (2019). The Age of Surveillance Capitalism. The Fightfor a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. Public Affairs.