|

Artícles

Silvia Pellegrini 1

Daniela Grassau 2

Soledad Puente 3

1 ![]() 0000-0002-8974-2996. Pontificia Universidad

Católica de Chile, Chile. spellegrini@uc.cl

0000-0002-8974-2996. Pontificia Universidad

Católica de Chile, Chile. spellegrini@uc.cl

2 ![]() 0000-0001-7846-8322. Pontificia Universidad

Católica de Chile, Chile. dgrassau@uc.cl

0000-0001-7846-8322. Pontificia Universidad

Católica de Chile, Chile. dgrassau@uc.cl

3 ![]() 0000-0002-4978-4729. Pontificia Universidad

Católica de Chile, Chile. spuente@uc.cl

0000-0002-4978-4729. Pontificia Universidad

Católica de Chile, Chile. spuente@uc.cl

Received: 24/01/2020

Sent to peers: 30/01/2020

Approved by peers: 17/03/2020

Accepted: 03/06/2020

To reference this article / para citar este artículo / para citar este artigo: Pellegrini, S., Grassau, D., & Puente, S. (2021). Disaster Coverage Model (DCM): Six Dimensions to Confront Activities and Workflows for Journalists and News Departments. Palabra Clave, 24(4), e2444. https://doi.org/10.5294/pacla.2021.24.4.4

Abstract

This work aims to identify, classify, and categorize relevant activities regarding professional journalistic work in major disaster coverage, and develop a conceptual model that organizes them theoretically. We conducted a series of empirical data collection stages (background gathering through in-depth interviews and content analysis) and later applied the theory-building block approach that uses concepts to create and operationalize constructs. The main result is a six-dimension model based on the traditional questions of the journalistic process: How, why, who, when, what, and where. It comprehensively addresses the multiple aspects involved in disaster coverage: emotional, logistic, professional, and ethical challenges, as well as timing, key actors/roles, and their needs and demands according to the disaster type and stage they face. The model also brings together a group of potential activities journalists must confront and carry out when covering major disasters or highly significant social crises. Its main contribution is to make a useful theoretical tool available to academia and the media, striving for a versatile matrix management approach.

Keywords (Source Unesco Thesaurus): Journalism; disaster management; risk management; coverage; communication; news departments; media.

Resumen

El objetivo de este trabajo es identificar, clasificar y categorizar las actividades pertinentes relativas al trabajo periodístico en la cobertura de desastres de gran magnitud, así como desarrollar un modelo conceptual que las organice teóricamente. Para ello se siguieron una serie de etapas empíricas de recopilación de datos (a través de entrevistas en profundidad y análisis de contenido) y luego aplicamos el enfoque teórico de construcción de bloques que utiliza conceptos para crear constructos y ponerlos en funcionamiento. El resultado principal es un modelo de seis dimensiones basado en las preguntas tradicionales del proceso periodístico: cómo, por qué, quién, cuándo, qué y dónde. Estas preguntas engloban las seis dimensiones detectadas que enfrenta el proceso de cobertura periodística de desastres de gran magnitud o incluso de crisis sociales de gran relevancia. El modelo propuesto abarca los múltiples aspectos que comprende la cobertura de desastres: los desafíos emocionales, logísticos, profesionales y éticos, así como las fases, los actores y roles principales, así como sus demandas y necesidades de acuerdo a la fase y/o el tipo de desastre que estén enfrentando. Sobre todo, interrelaciona al grupo de potenciales actividades que los periodistas deben enfrentar y ejecutar al cubrir desastres de gran magnitud o crisis sociales importantes. Su mayor contribución es hacer accesible una herramienta teórica útil tanto para la academia como para los medios, y que apunta a una gestión matricial y versátil de la información en estos casos.

Palabras clave (Fuente tesauro de la Unesco): Periodismo; gestión de desastres; gestión de riesgos; cobertura; comunicaciones; departamentos de noticias; medios de comunicación.

Resumo

O objetivo deste trabalho é identificar, classificar e categorizar as atividades pertinentes relativas ao trabalho jornalístico na cobertura de desastres de grande magnitude, bem como desenvolver um modelo conceitual que as organize teoricamente. Para isso, seguiu-se uma série de etapas empíricas de coleta de dados (por meio de entrevistas em profundidade e análise de conteúdo) e logo aplicou-se a abordagem teórica de construção de blocos que utiliza conceitos para criar construtos e colocá-los em funcionamento. O resultado principal é um modelo de seis dimensões baseado nas perguntas tradicionais do processo jornalístico: como, por que, quem, quando, o que e onde. Essas perguntas abrangem as seis dimensões identificadas que o processo de cobertura jornalística de desastres de grande magnitude ou de crises sociais de grande relevância enfrenta. O modelo proposto engloba os múltiplos aspectos que a cobertura de desastre compreende: desafios emocionais, logísticos, profissionais e éticos, bem como fases, atores e papéis principais, além de suas demandas e necessidades de acordo com a fase e/ou o tipo de desastre que estiverem enfrentando. Principalmente, inter-relaciona o grupo de potenciais atividades que os jornalistas devem enfrentar e executar ao cobrir desastres de grande magnitude ou crises sociais importantes. Sua maior contribuição é tornar acessível uma ferramenta teórica útil tanto para a academia quanto para os meios, e que aponta a uma gestão matricial e versátil da informação nesses casos.

Palavras-chave (Fonte tesauro da Unesco): Jornalismo; gestão de desastres; gestão de riscos; cobertura; comunicações; departamentos de notícias; meios de comunicação.

Introduction

Responding to journalism's main issues during the coverage of large-scale disasters or a highly significant social crisis (such as the current COVID-19 pandemic) is not professionally easy. Common challenges take on their deepest significances at the time, and authorities' and experts' answers are scarce and dispersed. There is weighty literature regarding journalism during this type of event, which has increased during the past 15 years, ranging from theoretical papers to very practical handbooks, with approaches from different disciplines (e.g., psychology, geography, engineering, logistics), so there has not been a thorough compilation of it. After that, during ten years of continuous research, our research team has led a successive series of research projects on journalism in times of disaster and has conducted an in-depth review of the academic and practical state of the art on the subject from different disciplines and organizations working with disaster management. Our objective is to identify, classify, and categorize relevant professional journalistic work in large-scale disaster coverage and to develop a conceptual model that theoretically organizes them from a matrix management approach.

The primary outcome of this paper is to make available a valuable theoretical tool for both academic and media work. It deals comprehensively with the multiple aspects involved in disaster coverage and enlightens the relationship between them; i.e., it allows the following elements to be included: emotional, logistic, professional, and ethical challenges, as well as timing and key actors/roles and their needs and demands according to the disaster type and stage they face.

The work is structured upon a qualitative analysis based on the theory-building block approach that uses concepts to build constructs and operationalize them. We followed five steps: construct definition, activities systematization according to the literature, experts' pre-test, multilevel outlook through iterative meetings, and validation based upon in-depth interviews.

A crucial contribution of this proposal is related to the demand of scholars and professionals for more theoretical elaboration on crisis communication and, subsequently, on disasters (e.g., Austin et al., 2012). In addition, general critics often blame researchers for concentrating on data collection without articulated theories. Those are precisely the ideas on which this study is based, seeking to conceptually structure the journalistic process during large-scale disasters or crisis coverages to understand better the process and support news departments with tools that should improve the management of critical, unexpected, unpredictable, routine-breaking events.

Organizing activities under multiple inputs allows actors in charge of disaster coverage to recognize fundamental elements, considering theirs and other actors' responsibilities and purposes. For example, a journalist might recognize key personal activities that can affect logistical issues during the coverage, which could disturb his/her outcomes, and thus prepare accordingly. In turn, a media executive may recognize the key activities he/she should undertake before the coverage ofa disaster, linked to the information challenges of his/her entire team. As a result, we developed a conceptual scheme that encompasses six dimensions defined by the traditional questions that shape the information process: How, why, who, when, what, and where.

Theoretical framework

From a media perspective, disasters break professional newsroom routines and challenge their members to work under extreme conditions (Ewart & McLean, 2018; Potter & Ricchiardi, 2006; Puente et al., 2013a; Quarantelli, 1996, 2005). These occasions alter the quality patterns of traditional journalism (Puente et al., 2013a, 2013b), especially when faced with continuous or uninterrupted coverage of large-scale events (Blondheim & Liebes, 2002). Following the above analysis, it seems evident that during disasters, the main problems encountered by media coverage are uncertainty and the urgency of responding to the need for information and psychological support of a large and vulnerable population (García Acosta, 2005; Gui et al., 2017; Mujica et al., 2020). The preceding requires a human and logistic effort beyond the reach of journalism (Kachali & Storrsjõ, 2018; Lowrey et al., 2007; Perry et al., 2001) or special preparation.

Practical/professional approach

To date, approaches to the subject have dealt mainly with practical issues, and it is easy to find a considerable number of manuals, guides, or handbooks, but very few approaches include an academic analysis of the items included in them. Moreover, information is often disaggregated and presented under different points of view, making its follow-up a real challenge sometimes. Handbooks are clear to point out the duties and responsibilities of journalists, editors, and media directors. Some basic criteria such as fairness, justice, honesty and decency, and source protection are continually present (Cooper, 2018; Ewart & McLean, 2019). They also emphasize that disaster coverage always deals with traumatized persons —victims suffering from extreme vulnerability—. So, journalists must be aware of the need for specific information control, and content, images, and sounds must be thoroughly reviewed and verified (Handout, 2014; Hight & Smyth, 2003; Institute for War & Peace Reporting, 2004; Linkins, 2011; Otieno, 2006; Panamerican Health Organization [PAHO], 2011; Ross, 2004; Scanlon, 2011; Silverman, 2014; Ulloa, 2011).

Some documents deal directly with journalistic coverage approaches such as the need of having interviews' guidelines, doing previous research on the geographic area to be covered, compiling statistics, getting acquainted with the mitigation aspects, or developing security measures for the journalistic team (Gearing, 2012; Hight & Smyth, 2003; International Federation of Red Cross, 2000; Otieno, 2006; PAHO, 2011). Fukunaga (2013) analyzes the language used in the case ofJapan's tsunami in 2011, pointing out the special care needed when referring to catastrophic events. Linkins (2011) refers to the journalist's role in responsible coverage of disasters and the importance of having a controlled speech.

Some handbooks provide guidelines to media directors and editors. They strive to have an impact on media policies regarding planning for emergency coverage, alert plans, pain treatment, or personnel preparedness (International Federation of Red Cross, 2000; Leoni et al., 2011; Ross, 2004; Ulloa, 2011). Others refer to the fact that journalists and their teams are exposed to situations that can affect them emotionally and increase their vulnerability (Fourie, n.d.; Gearing, 2012; The News Manual Online, n.d.). The works by Melki et al. (2013) and McMahon (2001) delve into journalists' trauma and stress, also showing the limited information and capacity of journalistic teams that cover disasters or catastrophic events.

Regarding victims and those affected by the disaster, some handbooks give recommendations for good treatment of grief, post-traumatic stress, and community expectation (Fourie, n.d.; Gearing, 2012; Handout, 2014; Hight & Smyth, 2003; McIntyre, 2003; Otieno, 2006; PAHO, 2011; Potter & Ricchiardi, 2006; Smyth, 2012; The News Manual Online, n.d.; Ulloa, 2011), while others try to guide journalists in situations of extreme vulnerability (wars, terrorism, armed conflicts) (Chandler & Landrigan, 2004; McIntyre, 2003; Reporters Without Borders, 2005; Small World News, 2012; Tahir, 2009).

Challenges facing a disaster

Disasters trigger a strong need for information: the population requires and demands to know as much as possible about what happened, who is in danger, and what authorities are doing (Swindell & Hertog, 2012; Toledano & Ardèvol-Abreu, 2013; Veil, 2012). The main reason for such a need is to establish a relation, be connected, and receive emotional support and a sense of community (Alkali & Habil, 2016; Puente et al., 2019). From the point of view of journalism, the previous work conducted by this research team focused on the detection and operationalization of these needs in four different types of challenges that the media and professionals must face during any disaster: emotional, logistic, ethical, and strictly informative (Puente et al., 2013a; Pellegrini et al., 2015). This work showed that it is possible to distinguish them clearly as different journalistic coverage requirements during disasters.

A large proportion of disasters mainly entail logistic challenges, producing connectivity and communication difficulties, complications of lodging and sustenance, or exposure to diseases or a lack of potable water in dangerous areas (Kovács & Spens, 2007; Noguera Vivo, 2005; Potter & Ricchiardi, 2006; Yez, 2013). The emotional challenge refers to the states of nervousness, tension, confusion, anguish, or stress experienced by journalists and other news professionals, as well as sources (Puente et al., 2013a, 2013b) while performing their role during a disaster with high emotional impact (Colón, 2005; Potter & Ricchiardi, 2006; Zelizer & Allan, 2011). According to the literature and experts, these professionals' mental structures are often not prepared to be exposed to such stressful situations (Buchanan & Keats, 2011; Freedy et al., 1994; Himmelstein & Faithorn, 2010).

The ethical challenge refers to journalists' internal debate between the need to inform, the potential violation of the victims' privacy rights during coverage, and the impulse to help in the tasks of assistance and rescue. Some authors consider that journalists might not have the capacity to sort stories, separating the aspects that invade the privacy of those that might clarify relevant aspects (Chouliaraki, 2010; Crawford & Finn, 2015; Etchegaray & Matus, 2015; Lozano, 2004). S ome argue that the media give too much space to testimonies rather than to objective information (Chouliaraki, 2010;Joye, 2018) and increase the violation of privacy rights (Lozano, 2004). Others argue that the morbid aspect of showing pain derives from the obligation of giving a human character to the news (Noguera Vivo, 2005, 2006), while Oyanedel and Alarcón (2010) insist that there is often a tendency to reinforce stereotypes.

Finally, the strictly informative challenges derive from the fact that journalists must face their social responsibility to inform (Burkhart, 1991; Orgeret, 2016) in a context marked by uncertainty (Crovi & Lozano, 2005). It necessarily entails problems of coverage oscillating from inaccuracy (Brusi et al., 2008) and improvisation on how to approach journalistic objectivity (Noguera Vivo, 2005) or how to select the appropriate sources or frames (Barrios et al., 2017; Focás & Zunino, 2019). In this regard, the contact with persons in a state of trauma possibly will obfuscate the gathering of trustworthy information and, consequently, the news media's work (Garfin et al., 2014; Hight & Smyth, 2003).

Roles/participants

The literature shows, in the case of disasters, a need for a response according to journalists' and experts' parameters. Nevertheless, there are tensions concerning the roles and actors in disaster situations: journalists and disaster managers/authorities usually disagree regarding the message's content, even if they need each other. This disagreement goes beyond what happens in the routine relationship between authorities (performing as sources) and j ournalists, and the tension tends to increase as politicians become involved in the lead up to disasters and as disasters unfold (Ewart et al., 2016; Grassau et al., 2021). Moreover, authorities and politicians are also the ones who get blamed if things go wrong (Arceneaux & Stein, 2006). In addition, in times of disaster and crisis, a public-private sector partnership/relationship is priceless (Cant, 2016).

Through social media —such as Twitter or Instagram—, ordinary people have an emergent role in covering disasters (Valenzuela et al., 2017); García-Santa et al. (2015) call it crowd as a censor. They are mainly used to reestablish personal relations (Austin et al., 2012) and to have some direct insights derived from the share and retrieval ofinformation in real-time (Parsons et al., 2015), which can be helpful to gain additional perspectives for disaster management. However, traditional media are still the most valuable tool in delivering information to the affected and the community (Ewart et al., 2016), and it increases insofar the role of journalists as first responders and significant witnesses of the authorities' and experts' activities (mitigation watchdogs) (Lowrey et al., 2007; Lozano, 2004; Olsen et al., 2003) emerges in disaster management (Wilkins, 2010, 2016).

An example can be found in Chile, where after the 8.8 Mw earthquake of February 2010, it was noticed that anchorpersons could adopt different roles during the coverage, such as informative, judgmental, and dialoguing with the audience. Those roles were modified according to journalists' personalities, the media's editorial line, and time (Grassau et al., 2019).

Kinds and phases of disasters

From another point ofview, disasters are characterized by different elements such as geographic, economic, and political conditions (Eshghi & Larson, 2008), the presence of experts in the management of the event (Landesman, 2011), and the degree oftrust in them (Dussaillant & Guzmán, 2014), among others. Most studies on journalistic coverage of disasters refer to the initial stage of the events or the first moment of social consciousness about it (Backfried et al., 2016). The literature recognizes different stages that occur cyclically: response, recovery, mitigation, and preparation (Hood & Jackson, 1992), which suffer several metamorphoses over time and get rooted in the population's day-to-day. The abnormal duration of some of these phases and their rooting in daily life makes them invisible in media content, although they profoundly impact society. This four-phase disaster classification —a common approach nowadays— began in the United States in 1978 (Altay & Green, 2006).

The part journalism plays in these four phases justifies the need to critically analyze its role in these events (Stolzenburg, 2007; Zelizer & Allan, 2011). Journalism often privileges speed over quality, which in critical situations can increase damage and extend the disasters' chronic effects (Hindman & Coyle, 1999; Olsen et al., 2003; Stolzenburg, 2007; Veil et al., 2008; Zelizer & Allan, 2004). The media state that the abundance of testimonies derives from a lack of official information and the public's need to know, but this can only be accepted during some stages after the event (Puente et al., 2013b).

The literature also distinguishes disasters based on various criteria. The most common is to sort them by origin: nature or human action, although there is also debate on this point. The difference between classifying disasters as natural or man-made seems to be losing significance, but from an informational perspective, informative differences prevail, primarily due to variations in sources and framing of news stories. Solely man-made disasters open a line on a different kind of responsibility that need to be taken.

Method

Study case

This work was completed in the framework of three State-funded research projects on the journalistic coverage of a series of major events in Chile during the last ten years, including earthquakes, wood fires, floods, volcanic eruptions, and oil spills. The main event we studied was the large Chilean earthquake that occurred on February 27 (27F), 2010, which was selected for its magnitude (8.8 Mw) and because it was followed by a tsunami warning in more than 50 countries across the Pacific Ocean. These events set the agenda of the Chilean media for several months, tested the routines of newsrooms, and forced the Chilean academia to review the national and international management procedures in different areas, including journalism.

This paper tries to answer the following research questions specifically:

RQ1: What are the relevant activities of professional journalistic work in major disaster coverage?

RQ2: What are the dimensions into which these activities can be classified?

RQ3: What are the elements that describe each of these dimensions?

RQ4: How can these dimensions be interrelated to achieve quality coverage?

To arrive at the theoretical model proposal presented in this article, we conducted a series of empirical data collection stages (background gathering through in-depth interviews and content analysis). Later, we applied the theory-building block approach that uses concepts to create and operationalize constructs.

Background gathering

In-depth interviews: Between 2011 and 2019, we conducted a field exploration consisting of 104 in-depth interviews with scholars, journalists, and editors of the mainstream media of Chile and other countries that provided data to identify the challenges to be addressed during coverages and determine their coincidence with the literature (Pellegrini et al., 2015). All these interviews were conducted face-to-face by the research team, audio-recorded, and transcribed. All interviewees signed an informed consent form. All interviews had a set of fixed questions (although open to additional questioning). All the steps in this process were approved by the ethics committee of the university where the study was carried out. On average, the interviews lasted at least 40 minutes.

Specifically, we conducted:

• Between 2011-2013: Twenty in-depth interviews with journalists and editors of the mainstream media in Chile who had coverage responsibilities in the early hours of the 2010 earthquake and other relevant disasters. The sample included 16 journalists, two editors, and two media directors from Chile's four largest national over-the-air television stations1 that broadcast during the first few hours following the 2010 earthquake (Puente et al., 2013a). We created two open-ended questionnaires: 21 questions for j ournalists and 27 questions for editors and directors. The questionnaires included questions such as: What were the conditions in which you performed your work? Had the networks made any preparations for dealing with such events? What happens to journalists when they are exposed to a disaster? What journalistic and editorial challenges did this kind of coverage pose?

• Between 2015-2019: Eighty-four in-depth interviews with academic and professional experts from different countries: six in the UK, 25 in Chile, four in Japan, 22 in the USA, and 27 in Australia. All these countries were chosen because they have significant theoretical development on disasters and are frequently affected by these events. This last aspect is beneficial in this case since all these countries have expert organizations in disaster management. The objective of these interviews was to collect and discuss the different dimensions related to the journalistic disaster coverage, considering surrounding conditions, institutional conditions, professional practices and routines, and personal and professional attributes and needs. Thus, we determined those aspects that are stable and those that can change depending on the disaster's geographic, economic, political, or social conditions.

Content analysis: Following the field exploration, we applied different stages of content analysis to a vast sample of Chilean news using the instrument developed by the team (Puente et al., 2013a), based on the Added Journalism Value methodology (VAP, for its acronyms in Spanish) (Pellegrini et al., 2011). The content analysis instrument was applied to:

• A sample of 1,612 news stories from Chile's leading TV channels after the 2010 earthquake (Pellegrini et al., 2015)

• A sample of 1,169 news stories after the 2014 earthquake (Puente et al., 2019)

• A sample of more than 7,703 newspaper news stories about four types of disasters (a wood fire, floods, an oil spill, and an earthquake) collected between 2018 and 2019 to determine the differences among the journalistic coverage during different kinds and phases of disasters

The variables measured were ability to select and deliver data (verifiable data; exclusive material; place of occurrence); ability to process data and images (headlines; archive material; framing; editorial focus; relevance of the consequences); skills and creativity to develop a balanced news budget (thematic hierarchy); ability to detect and access appropriate sources (types of sources; actors and roles); ability to balance sources (number of sources); respect for privacy and pain (impact resources; identity protection); concern for language and tone (emotional tone; narrative basis; qualifying adjectives and adverbs; editing resources; graphic resources), and support of victims (ability to differentiate between roles).

The results of these works allowed the team to determine, for example, that a) the thematic hierarchy gave priority to urgencies over disaster facts; b) there was weak presence of authorities, experts, and documents, but many testimonies and c) there was a blurred framing in many news units (Puente et al., 2019). Additionally, we confirmed that uncertainty and poor elaboration were the features of journalistic coverage during the first 24 hours after the onset of a disaster; from the second day, coverage showed a higher degree of processing and, after that, quality professional standards tended to increase (Puente et al., 2013a, 2013b, 2015).

Theory-building block approach

Having this background, we applied a theory-building block approach (Henneberg & O'Shaughnessy, 2007). It uses concepts to build constructs and operationalize them, establishes relationships between them and, eventually, with reality (Doty & Glick, 1994; Dubin, 1978; Whetten, 1989), and shows how they were selected and how they are connected or can be connected in the future (Sutton & Staw, 1995). In other words, the concept-structure building is a set of concepts and relationships statements that allows understanding, describing, explaining, evaluating, predicting, and controlling phenomena (Cragan & Shields, 1998). It is crucial for several reasons: it guides future research, allows integrating research results that have numerous and (usually) disparate variables (Smeltzer & Suchan, 1991), and is a support for change based on evaluation and innovation. Models must be pragmatic and have empirical capacity. This work built the conceptual model proposed in this paper and is based on the five steps below.

Step 1: Definition of the construct

Upon the theory-building blocks proposal (Henneberg & O'Shaughnessy, 2007), the starting point was the development of an operational definition of what we understand by information coverage of disasters:

what news departments do when they report on phenomena of great social importance that, due to their magnitude, break the role of institutions, interfere with journalistic routines and force professionals to work under intense pressure, uncertainty and personal and social vulnerability. (Puente et al., 2013a, p. 109)

Step 2: Systematization of activities according to literature

We reviewed 22 guides or handbooks from different governmental organizations and experts on disaster management and 450 mainstream papers published in the last 20 years. Those documents were analyzed and codified in a categories data matrix built upon an axial and open codification. With these two sources, we made a list of over 200 potential activities that journalists and other newspersons should or could perform when covering a disaster and systematized them in a data matrix.

Step 3: Experts' pre-test

To test that operationalization (Step 1) and systematization (Step 2) were going on the right path, we discussed each of these activities with the experts and scholars previously mentioned through in-depth interviews conducted by our team. These two were simultaneous processes.

Step 4. Multilevel outlook

In this step, we focused on modeling the results in a scheme able to theoretically structure the activities involved (Mahoney & Sanchez, 2004), considering that "micro and macro structures and their relationships need to be developed theoretically" (Henneberg & O'Shaughnessy, 2007, p. 14). To do so, we held a series of discussions in iterative meetings between the research team members —1.5 to 3 hours weekly— for a year.

Finally, we continued with the previously mentioned in-depth interviews in Chile and other countries with journalists, experts, and disaster management authorities. Steps 4 and 5 were simultaneous. The on-field acquired knowledge showed significant moments of individual decision-making in disaster coverage that cannot be avoided because they depend on the team, the specific media, and cultural characteristics. Nevertheless, other decision aspects can be anticipated or supported if previously known.

Main results

Upon the above steps, we made a list of over 200 activities that journalists and other newspapers should perform when covering a disaster, according to literature and the in-depth interviews with professionals, scholars, and experts. By ordering these activities, we concluded that disaster coverage was a multilevel process theoretically explained through the basic journalistic questions —why? what? how? who? where? when?— and that there was a way to justify the answer to each question and establish relationships within them and between them and reality from a matrix management approach. Specifically, we concluded that based on the main activities detected, the following questions could be answered:

How should journalistic coverage of disasters be done? According to theory and practice, it derives from the main challenges that j ournalism must face on such occasions (logistic, emotional, informative, and ethical).

Why is it covered that way? It seeks answers to needs, requirements, and demands that must be fulfilled during the journalistic process and provides framings.

Who does or should do each task? It looks upon participants or persons/roles that have direct activities or oversee the journalistic coverage and then, defines a core task force.

When should each member do what? It addresses the process under time considerations related to the disaster.

What are the specific characteristics of the kind of disaster the team is dealing with? It tries to introduce nuances in the coverage of disasters by determining the informative specificities of each kind.

Where is the team working at in a disaster's evolution? It deepens nuances by recognizing that disaster stages or phases have their own informative requirements and introduces the need for medium- and long-term follow-ups.

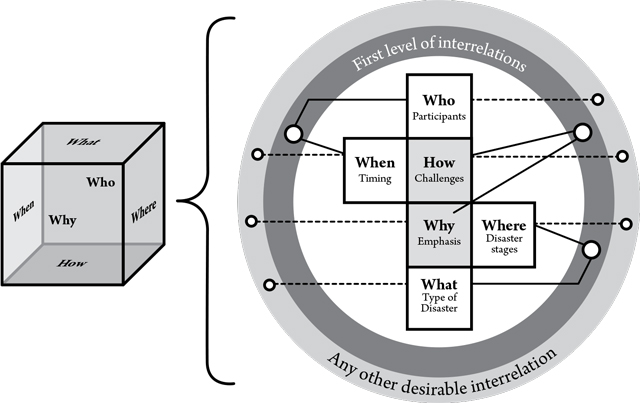

These questions provided a matrix that can be graphically interpreted as a cube, which can be metaphorically filled by activities: each side provides the entrance to a specific set of activities that respond to one of the six journalistic dimensions (how? why? who? when? what? and where?). Thus, the activities are separately analyzed, achieved, and combined, but are interrelated to accomplish comprehensive and adequate coverage of disasters. The main results are shown in Figure 1 and Tables 1 to 5 that summarize them through examples of activities and relations.

Figure 1. Six-Dimension Disaster Coverage Model.

Source: Own elaboration.

By providing multiple entries to the different activities involved, the proposed model (Figure 1) represents modular, simplified, and efficient access, especially considering that it includes a considerable number of activities to face in a highly stressful moment, with many actors and with extreme urgency.

As an answer to the questions representing the six dimensions, the how was defined by the four challenges reviewed in this article that journalism must face when covering disasters: logistical, emotional, ethical, and strictly informative.

The general descriptors for the why dimension were defined as the requirements or emphasis given to that specific action: personal needs of the team involved, third-party needs from the coverage, media requirements and external demands, mainly those responding to the public interest, experts, and disaster managers/authorities; hence, providing framings.

The who dimension allows us to distribute activities among different actors or participants that were the core decision team: journalists, producers, editors, and media executives.

The when dimension provides timing considerations and focuses on when the journalistic team must perform every activity: before, during, or after the event, or if it addresses a permanent activity.

The what dimension tries to introduce nuances to the journalistic coverage of disasters by considering their differences beyond the general description of sudden, unpredictable, and dangerous events. It divides activities between those required in natural or man-made disasters and reaction times: immediate (less than 24 hours) or prolonged (more than 24 hours).

Finally, the where dimension recognizes the informative needs by stages or phases of the disaster. The objective of this side of the cube is to recognize where is the team working at in a disaster's evolution. Thus, we chose the traditional division of four stages due to its clarity: preparedness, mitigation, response, and recovery.

We also established the first interrelations between dimensions (questions or cube faces) to improve the theoretical framework clarification and make the model more useful. Each dimension or side of the cube has been primarily related to a second one to provide a new point of view of the model, resulting in three main crossings: how and why, who and when, and what and where, although the model also offers other possibilities (i.e., what and when, who and how). The result is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Disaster Coverage Model breakdown (or apportionment)

Dimensions (cube faces) |

Point of view |

Types of actions |

How: Challenges |

Logistic challenges |

Health

and safety: Activities and decisions through which participants (producers,

journalists, editors, executives) are physically protected Internal

organization: The preparation of the media or organization to face a disaster |

Emotional challenges |

Emotional

balance: Personal activities and decisions to be emotionally aware of |

|

Ethical challenges |

Personal

attitude: Personal values present in j ournalists/editors

when covering disasters |

|

Strictly informative challenges |

Professional

decisions: Specific features of professional decision-making in case of

disaster |

|

Why:Emphasis |

Personal needs |

Health

and safety |

Third-party needs |

Internal

organization |

|

Media requirements |

Inputs

and backups |

|

External demands |

Access

and relationships |

|

Who: Participants |

Producers |

Types of actions as previously established in how and why according to each participant |

When: Timing |

Always |

Types of actions, as previously established in how and why, according to each moment |

What: Kinds of Disasters |

Natural

with immediate reaction |

It

expands, for example, into: |

Where: Phases |

Preparation

phase |

It

expands, for example, into: |

Source: Own elaboration.

The following are examples of how the dimensions or cubes faces may dialogue and constitute a matrix management approach.

The relation between how and why

The relation between how and why deals mainly with aspects of journalistic activity, thus providing the model's core aspects. These two questions (how should journalistic coverage of disasters be done? and why is it covered in that way?) were the most difficult areas to define, put in order, and interrelate because they represent the core aspects of the professional activities involved in the coverage process and directly affect the information quality.

Using the sides of the cube how and why together, the journalistic activities are thoroughly reviewed and analyzed using specific descriptors. As stated before, how descriptors are logistical, emotional, ethical, and strictly informative challenges (Table 2), while why descriptors involve different emphases or needs (personal needs, third-party needs, media requisites, and external demands). Table 3 shows how the specific descriptors are listed. The different activities registered in the model are grouped in each slot, so it is possible to analyze or work either with one of them or with a specific group, such as a vertical line (detailed descriptors for ethical challenges) or a horizontal line (all activities concerning the subject).

Table 2. Zooming in on how descriptors: Journalistic standards affected by challenges in disaster coverage

Dimension |

Point of view: Challenges |

||

Challenges |

Descriptive elements |

Journalist standards affected |

|

How |

Logistic |

Communication

and connectivity |

Thematic hierarchy: Journalists cover news in the areas they can reach, which are not always the more important |

Emotional |

Empathy

with victims |

Scope of consequences: By narrowing sources down to testimonials mainly, a considerable percentage of the broadcasted stories is of particular relevance or essential for a tiny group. |

|

Ethical |

Transgression

of private rights (people's honor and

intimacy) |

Accuracy and significance in news outcomes decrease: Emotion exacerbation shadows the news' significance |

|

Strictly informative |

Lack of information and sources: The people officially in charge of the emergency do not always have reliable data to deliver Continuous coverage: Journalists must constantly look for ways to tell stories that support the need for ongoing news |

Framing:

Most of the news do not have a detectable frame and,

if there is one, the most common is human interest, followed by allocation

of responsibilities. |

|

Source: Own elaboration.

Table 3. Specific how and why descriptors

CHALLENGES (How) |

LOGISTIC |

EMOTIONAL |

ETHICAL |

STRICTLY INFORMATIVE |

EMPHASIS. (Why) |

||||

PERSONAL NEEDS |

Health and security |

Emotional balance |

Personal attitude |

Professional decisions |

THIRD-PARTY NEEDS |

Internal organization |

Concern for others' needs |

Dealing with victims |

Reporting and sources |

MEDIA REQUISITES |

Inputs and backups |

Training and prevention |

Pain and violence representation |

Organization and news production |

EXTERNAL DEMANDS |

Access and relationships |

Facing the situation |

Story selection |

Focus and themes |

Source: Own elaboration.

The relation between who and when

Using who and when together, participants can select activities that belong only to their specific role, but they might also be aware of what to expect from other relevant actors. The main participants of the informative process are journalists (including photojournalists), producers, editors, and media executives. Crossing them with a timing process enables each participant to place the activities in a personalized order and establish a personal plan (i.e., activities to be conducted throughout the whole process: before, during, and after the disaster). As shown in Table 4, the relation among who and when allows us to build and achieve customized agendas and allocate responsibilities and participation in an orderly manner. It even leads to a first attempt to organize roles for the special tasks in the newsroom during this disruptive situation.

Table 4. Who and when crossing examples

participants (Who) |

JOURNALISTS |

PRODUCERS |

EDITORS |

EXECUTIVES |

TIMING (When) |

||||

ALWAYS OR CONSTANT |

Updating sources Awareness of personal needs Periodical training |

Awareness of a lack of logistics Preparing an alternative newsroom Periodically updating protocols |

Supervising the technical and logistic supply stock Periodically updating protocols and source lists Listing trained personnel |

Awareness

and consideration of the needs for coverage of a disaster |

BEFORE THE DISASTER |

Physical

fitness Acknowledgment of risks |

Periodically

updating training needs Bringing equipment needs to the people in charge |

Distributing

eventual emergency shifts and duties |

Providing an adequate budget and specific technologies Requiring adequate personnel training. Hiring the necessary personnel |

DURING DISASTER COVERAGE |

Keeping emotional and physical stability Supplying the necessary information without overreacting (via traditional media and social media) Keeping in mind the need to relate not only to victims but to official sources and experts |

Providing

an internal and external communication system. |

Keeping

permanent communication with the onsite journalistic team for editing reasons

Providing support and free time to onsite personnel |

Keeping constant relations with editors Supervising the adequate flow of internal communication (on different platforms) Keeping in mind the social significance of adequate disaster coverage |

AFTER DISASTER COVERAGE |

Periodical follow-up on stories and authorities' effectiveness Supplying information according to stages of development Looking for psychological support to avoid potential trauma |

Reviewing

the inventory Analyzing the following stages needed |

Developing

evaluation methods such as a general meeting with those involved Providing

therapy to support those who need it |

Leading

an evaluation meeting |

Source: Own elaboration.

The activities listed regarding who and when potentially outline how to organize the newsroom when covering a disaster. More than names, roles are significant for a better understanding of the activities and their relationships since they represent significant changes in the everyday work of news departments. Those activities require an editor specially nominated for the event, ideally with previous experience in the role.

Evidence shows that work is divided into two main areas: a journalistic editor in charge of field action and a supervisor editor in the newsroom. The number of people in the field depends on the magnitude of the disaster coverage. The event can be covered by one person who performs the roles of journalist/photojournalist, producer in charge of logistics, and helps and assists the victims. In other cases, these roles are divided into several people.

The role of the supervisor editor is the main difference with regular coverage. This person must be permanently in touch with the field team for emotional support and to make sure they are safe. This same role is taken by the person liaising with the producer to respond to new logistical needs, and with one or more phone reporters who receive updates or requirements from the audience or third parties.

The relation between what and where

As stated before, the model's last level (the relation between what and where) has significant and unique informational requirements derived from each type and phase of a disaster and, subsequently, cannot be fully shown in the length of this article. It recognizes the different informative needs underlying types and stages of disasters and requires extensive analysis insofar they deal only with concrete activities. Nevertheless, some alternatives to the kind of nuances that can be introduced in specific disaster coverage are shown in Table 5.

Table 5. Examples of how the relation between what and where introduces nuances

Type of disaster (What) |

Natural protracted Floods |

Natural immediate Earthquakes Tsunamis |

Man-made protracted (eventually) Pandemics |

Man-made immediate (eventually) Fires |

Phases (Where) |

||||

Preparedness |

Watchdog actions on evaluation of previous experiences and public and private policies |

Covering the implementation of people's warning alternatives and following up on technological updates |

Developing news stories on strategies and public policies to prepare the population and informing about public policies on health security |

Reporting on warning for nature care, restricted areas, or dangerous seasons |

Response |

Reporting on measures for helping the population and draining water |

Coverage about the care of victims and immediate new dangers |

Reporting about shelters, safety, physical and psychological care of the population |

Coverage about stopping actions |

Recovery |

Investigating economic and environmental effects. |

Psychological and physical recovery stories. |

Follow-up on science developments, peoples' awareness of dangers, as well as attitudes in the aftermath |

Personal and natural recovery |

Mitigation |

Searching for causes and measures to avoid them |

Follow-up on needs, projects, and results |

Follow-up of new solutions or alternatives to public policies on the matter, as well as people's attitudes towards the issue |

Searching for responsibilities |

Source: Own elaboration.

Discussion and conclusions

The main specific objective of this study was to identify, classify, and categorize relevant activities regarding professional journalistic work in major disaster coverage and develop a conceptual model that theoretically organizes them in search of a flexible matrix management approach.

This work allowed us to list about 200 activities that newsrooms should carry out when covering highly relevant social crises or large-scale disasters. In search of a flexible and comprehensive matrix, those activities were classified, sorted, and related according to the following six questions: How should journalistic coverage of disasters be done? Why is it covered that way? Who does or should do each task? When should each member do what? What are the specific characteristics of the disaster the team is dealing with? Where is the team working at in a disaster's evolution? The ordering was achieved using the traditional questions that shape the information process (how, why, who, when, what, where) to find a recognized professional journalistic attack-line and a manageable, easy-to-understand tool.

By recognizing the main activities of the news-making process, we developed a theoretical model able to anticipate the need for some decision making or to support it in the information coverage of a disaster. In addition, it could help to focus better on some faded frames detected in many news stories during specific disaster coverages. The model included the above-mentioned six dimensions and was graphically conceived as a multiple-entry cube that establishes interrelationships among the hundreds of activities needed in the journalistic coverage of disasters, providing a versatile environment able to be updated and adapted —regarding the activities— to the needs of any newsroom management.

The relation between the dimensions how and why became the model's core because it was the way to order the main activities of journalism. Who and when together provide a much more practical way to personalize agendas and even organize a newsroom. Finally, what and where represent nuances and sensitivities for specific activities in covering different stages and characteristics of a particular disaster.

This matrix development allowed us to point out strategic moments in decision-making, disaster management issues, skill needs, and other topics. That is why we firmly believe the model is likely to be applied in several levels, ranging from operative decisions to frame, and gives meaning to the coverage of large-scale disasters or even a highly significant social crisis.

Analyzing the process of journalistic coverage of disasters within this six-dimension perspective showed multiple possibilities for its use and flexible adaptability to specific users, media, countries, or cultures. It also offers a controllable and comprehensible model for the significant number of activities deemed necessary by researchers and professionals in many countries. Another fundamental richness of the model is the possibility of establishing other relationships between activities by linking parameters differently (e.g., what and when, who and how).

The recognition of adverse situations in professional performance helps limit their effects by anticipating activities that could reduce their impact; thus, the scheme also centered on providing elements to improve quality in these areas, such as those represented by specifiers in stages and types of disasters.

It is also a valuable tool to prepare or upgrade journalists' knowledge to cover such events and not solely rely on experience. Moreover, local and international evidence shows that disasters are likely to increase (United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction [UNISDR], 2014). The scheme can also be used as a primary model to produce R&D software for matrix management of quality news coverage in case of disasters, a future aim of the research group.

In conclusion, a preexisting and well-known model of journalistic action in significant crisis and disaster management should improve the quality standard of informative coverage and news outcomes. It would be achieved by reducing some critical problems faced by media coverage in case of disaster: uncertainty and the urgency to respond to the need for information and support from a large and vulnerable population.

The following steps would be analyzing how disaster coverage evolves during the different stages of the events and according to population needs, and how these stages, the primary sources, or the characteristics vary if these are natural events (with previously known causes) or man-made events (revolts, terror, or war), where framings and sources also deal with sides, guilt, security, and other issues. Nevertheless, it must be noted that there are other crises —such as the COVID-19, a pandemic event which started at the end of 2019 and continues through 2021 — where causes are not so clearly established; a priori, they seem to be able to be covered with the proposed model. This kind of event entails an appealing challenge to our team's following research to test our six-dimension model in such contexts.

Finally, we also strongly believe that the proposed approach should help to better serve the expectations of audiences, experts, and disaster managers/authorities without compromising the journalists' freedom.

1 Three private stations, Canal 13, Chilevisión, and Mega, plus Television Nacional de Chile (TVN), the only publicly owned network station funded through advertising and without major State subsidies.

References

Alkali, W., & Habil, H. (2016). Media Coverage on Disasters: The Present State of Affairs. Malaysian Journal of Languages and Linguistics (MJLL), 5(2), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.24200/mjll.vol5iss2pp1-12

Altay, N., & Green III, W. G. (2006). OR/MS research in disaster operations management. European journal of operational research, 175 (1), 475-493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2005.05.016

Arceneaux, K., & Stein, R. M. (2006). Who is held responsible when disaster strikes? The attribution of responsibility for a natural disaster in an urban election. Journal of Urban Affairs, 28(1), 43-53. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0735-2166.2006.00258.x

Austin, L., Fisher, Liu B, & Jin, Y. (2012) How audiences seek out crisis information: exploring the social-mediated crisis-communication model. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 40(2), 188-207. https://doi.org/10.1080/00909882.2012.654498

Backfried, G., Schmidt, C., Aniola, D., Meurers, C., Mak, K., Göllner, J., Peer, A., Quirchmayr, G., Czech, G., & Glanzer, M. (2016). A general framework for using social and traditional media during natural disasters: Quoima and the central European floods of 2013. In G. Rogova & P. Scott (Eds.), Fusion Methodologies in Crisis Management (pp. 469-487). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1080/00909882.2012.654498

Barrios, M. M., Arroyave, J., & Vega, L. (2017). El cambio de paradigma en la cobertura informativa de la gestión de riesgo de desastres: retos y

oportunidades. Chasqui. Revista Latinoamericana de Comunicación, (136), 129-144. https://doi.org/10.16921/chasqui.v0i136.3318

Blondheim, M., & Liebes, T. (2002). Live television's disaster marathon of September 11 and its subversive potential. Prometheus, 20(3), 271-276. https://doi.org/10.1080/08109020210141434

Brusi, D., Alfaro, P., & González, M. (2008). Los riesgos geológicos en los medios de comunicación: el tratamiento informativo de las catástrofes naturales como recurso didáctico. Enseñanza de las Ciencias de la Tierra, 16(2), 154-166. http://hdl.handle.net/10256/15351

Buchanan, M., & Keats, P. (2011). Coping with traumatic stress in journalism: A critical ethnographic study. International journal of psychology, 46(2), 127-135. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207594.2010.532799

Burkhart, F. N. (1991). Journalists as bureaucrats: perceptions of 'social responsibility' media roles in local emergency planning. International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters, 9(1), 75-87.

Cant, D. (2016, November). What Matters Most Is Not the Size of the "Storm" but the Scale ofthe Impact. NATO Science for Peace and Security Series - D: Information and Communication Security, 47, 143-146. https://doi.org/10.3233/978-1-61499-716-0-143

Chandler, D., & Landrigan, I. (2004). A Journalist's Guide to Covering Bioterrorism (2nd ed.). Radio and Television News Directors Foundation. https://www.rtdna.org/uploads/files/bioguide.pdf

Chouliaraki, L. (2010). Ordinary witnessing in post-television news: towards a new moral imagination. Critical discourse studies, 7(4), 305-319. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405904.2010.511839

Colón, A. (2005, January 10). Trauma Takes Toll on Journalists Covering Disasters. Poynter. https://www.poynter.org/reporting-editing/2005/trauma-takes-toll-on-journalists-covering-disasters/

Cooper, G. (2018). Reporting Humanitarian Disasters in a Social Media Age. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351054546

Cragan, J. F., & Shields, D.C. (1998). Understanding communication theory: The communicative forces for human action. Pearson.

Crawford, K., & Finn, M. (2015). The limits of crisis data: analytical and ethical challenges of using social and mobile data to understand disasters. GeoJournal, 80(4), 491-502. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-014-9597-z

Crovi, D., & Lozano, C. (2005). Calidad frente a incertidumbre: miedos y riesgos por ver la televisión [Quality as opposed to uncertainty: fear and risks of watching]. Comunicar, 25(2), 322-323. https://doi.org/10.3916/C25-2005-126

Doty, D. H., & Glick, W. H. (1994). Typologies as a Unique Form of Theory Building: Toward Improved Understanding and Modeling. Academy of Management Review, 19(2), 230-251. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1994.9410210748

Dubin, R. (1978). Theory Development. Free Press.

Dussaillant, F., & Guzmán, E. (2014). Trust via disasters: the case of Chile's 2010 earthquake. Disasters, 38(4), 808-832. https://doi.org/10.1111/disa.12077

Eshghi, K., & Larson, R. C. (2008). Disasters: lessons from the past 105 years. Disaster Prevention and Management: An International Journal, 17(1), 62-82. https://doi.org/10.1108/09653560810855883

Etchegaray, N., & Matus, A. (2015). Evolución de la cobertura de la pobreza entre 2005 y 2014: qué ha cambiado y qué no en los noticiarios de televisión abierta en Chile [Evolution of poverty coverage between 2005 and 2014: What has changed and what has not in prime television newscasts in Chile]. Cuadernos.Info, (36), 53-69. https://doi.org/10.7764/cdi.36.727

Ewart, J., & McLean, H. (2018). Best practice approaches for reporting disasters. Journalism, 20(12), 1573-1592. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884918757130

Ewart, J., & McLean, H. (2019). News media coverage of disasters: Help and hindrance. Journal of Applied Journalism & Media Studies, 8(1), 115-133. https://doi.org/10.1386/ajms.8.1.115_1

Ewart, J., McLean, H., & Ames, K. (2016). Political communication and disasters: A four-country analysis of how politicians should talk before, during and after disasters. Discourse, Context & Media, 11, 3-11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcm.2015.12.004

Freedy, J. R., Saladin, M., Kilpatrick, D., Resnick, H., & Saunders, B. (1994). Understanding acute psychological distress following natural disaster. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 7(2), 257-273. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.2490070207

Focás, B., & Zunino, E. (2019). Territorios, tópicos y fuentes de la inseguridad. Un estudio sobre la prensa argentina. Cuadernos.Info, (45), 73-93. https://doi.org/10.7764/cdi.45.1492

Fourie, C. (n.d.). Trauma support. Fair Reporters. https://fairreporters.wordpress.com/ resources/trauma-support-advice/

Fukunaga, H. (2013, June). The imminence of Giant Tsunami Hazard and the Revision of Tsunami Warnings/Advisories. How Information Distribution by Municipalities and the Media will Change. NHK. https://www.nhk.or.jp/bunken/english/reports/summary/201306/01.html

García Acosta, V. (2005). El riesgo como construcción social y la construcción social de riesgos. Desacatos. Revista de Antropología Social, 19, 11-24.

García-Santa N., García-Cuesta E., & Villazón-Terrazas B. (2015). Controlling and Monitoring Crisis. In European Semantic Web Conference (pp. 46-50). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-25639-9_9

Garfin, D. R., Silver, R. C., Ugalde, F. J., Linn, H., & Inostroza, M. (2014). Exposure to rapid succession disasters: A study of residents at the epicenter of the Chilean Bío Bío earthquake. Journal of abnormal psychology, 123(3), 545-556. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037374

Gearing, A. A. (2012) Lessons from media reporting of natural disasters: a case study of the 2011 flash floods, in Toowoomba and the Lockyer Valley [Doctoral dissertation, Queensland University of Technology]. http://eprints.qut.edu.au/61628/

Grassau, D., Puente, S., Vatter, N., & Rojas, R. (2019). Perfiles y roles de los conductores de TV en momentos de desastres: propuesta conceptual a partir del caso del terremoto del 27F en Chile. Revista De Comunicación, 18(2), 155-175. https://doi.org/10.26441/RC18.2-2019-A8

Grassau, D., Valenzuela, S. & Puente, S. (2021). What 'Emergency Sources' Expect from Journalists: Applying the Hierarchy of Influences Model to Disaster News Coverage. International Journal of Communication, 15, 1349-1371. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/14450/3385

Handout, M. (2014). Reporting on Humanitarian Crises: A Manual for Trainers & Journalist and an Introduction for Humanitarian Workers.

Hood, C., & Jackson, M. (1992). The new public management: a recipe for disaster? In D. Parker & J. Handmer (Eds.), Hazard Management and Emergency Planning-Perspectives on Britain (pp. 109-125). James & James Science Publishers.

Gui, X., Kou, Y., Pine, K. H., & Chen, Y. (2017, May). Managing uncertainty: using social media for risk assessment during a public health crisis. In Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 4520-4533). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3025453.3025891

Henneberg, S. C., & O'Shaughnessy, N. J. (2007). Theory and concept development in political marketing: Issues and an agenda. Journal of Political Marketing, 6(2-3), 5-31. https://doi.org/10.1300/J199v06n02_02

Hight J., & Smyth, F. (2003). Tragedies and journalists: a guide for more effective coverage. Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma. https://dartcenter.org/sites/default/files/en_tnj_0.pdf

Himmelstein, H., & Faithorn, P. (2010). Eyewitness to disaster: how journalists cope with the psychological stress inherent in reporting traumatic events. Journalism Studies, 3(4), 537-555. https://doi.org/10.1080/19376529909391705

Hindman, D. B., & Coyle, K. (1999). Audience orientations to local radio coverage of a natural disaster. Journal of Radio & Audio Media, 6(1), 8-26. https://doi.org/10.1080/19376529909391705

Institute for War & Peace Reporting. (2004). Reportaje para efectuar cambio: un manual para periodistas locales en zonas de crisis [Reporting for a change: a handbook for local journalists in crisis areas]. https://iwpr.net/printed-materials/reporting-change-handbook

International Federation of Red Cross. (2000). Introduction to disaster preparedness. Disaster preparedness training programme. http://www. ifrc.org/Global/Publications/disasters/all.pdf

J oye, S. (2018). When societies crash: a critical analysis of news media's social role in the aftermath of national disasters. Journal of Applied Journalism & Media Studies, 7(2), 311-327. https://doi.org/10.1386/ajms.7.2.311_1

Kachali, H., & Storrsjö, I. (2018). An inquiry into public procurement for the civil preparedness space. A case study in Finland. In M. Christopher & P. Tatham (Eds.), Humanitarian logistics: Meeting the challenge of preparing for and responding to disasters (pp. 168-186). Kogan Page Publishers.

Kovács, G., & Spens, K. M. (2007). Humanitarian logistics in disasters relief operations. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 37(2), 99-114. https://doi.org/10.1108/09600030710734820

Landesman, L. Y. (2011). Public health management of disasters. American Public Health Association. https://doi.org/10.2105/9780875530048

Leoni, B., Radford, T., & Schulman, M. (2011). Disaster Through a Different Lens: Behind Every Effect, there is a Cause: A guide for Journalist Covering Disaster Risk Reduction. United Nations. https://www.unisdr.org/files/20108_mediabook.pdf

Linkins, J. (2011, March 12). Advice For Journalists - Disaster Preparedness Edition. Huff Post. https://www.huffpost.com/

Lowrey, W., Evans, W., Gower, K., Robinson, J., Ginter, P., McCormick, L., & Abdolrasulnia, M. (2007). Effective media communication of disasters: Pressing problems and recommendations. BMC Public Health, 7(1), 97. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-7-97

Lozano, C. L. (2004). Medios de comunicación y catástrofes: ¿tratantes de información? [Mass media and catastrophes: information dealers?] In La comunicación en situaciones de crisis: del 11M al 14M: actas del XIX Congreso Internacional de Comunicación [Communication

in crisis situations: from 11M to 14M: Proceedings of the XIX International Communication Congress] (pp. 563-574). EUNSA.

Mahoney, J. T., & Sanchez, R. (2004). Building New Management Theory by Integrating Processes and Products of Thought. Journal of Management Inquiry, 13(1), 34-47. https://doi.org/10.1177/1056492603260658

McMahon, C. (2001). Covering disaster: A pilot study into secondary trauma for print media journalists reporting on disaster. Australian Journal of Emergency Management, 16(2), 52-56. https://search.informit.com.au/documentSummary;dn=378230090783367;res=IELHSS

McIntyre, P. (2003). A survival guide for journalists. International Federation of Journalists.

Melki, J. P., Fromm, M. E., & Mihailidis, P. (2013). Trauma journalism education: teaching merits, curricular challenges, and instructional approaches. Journalism Education, 2(2), 62-77. Mujica, C., Grassau, D., Bachmann, I., Herrada, N., Flores, P.M., & Puente, S. (2020). Percepciones de la audiencia respecto del uso del melodrama en noticias por televisión: entre el entusiasmo y el desprecio [Audience Perceptions of the Use ofMelodrama in News Programs: Between Enthusiasm and Contempt]. Palabra Clave, 23(4), 1-34. https://doi.org/10.5294/pacla.2020.23.4.1

Noguera Vivo, J. M. (2005). Informar emociones: el lenguaje periodístico en la cobertura de catástrofes [Informing emotions: the journalistic language in the coverage of catastrophes]. LibrosEnRed.

Noguera Vivo, J. M. (2006). El framing en la cobertura periodística de la catástrofe: las víctimas, los culpables y el dolor [Framing in the journalistic coverage of catastrophes: the victims, the culprits and the pain]. Spherapública, (6), 193-206. http://sphera.ucam.edu/index.php/sphera-01/article/view/49

Olsen, G. R., Carstensen, N., & Hoyen, K. (2003). Humanitarian crises: What determines the level of emergency assistance? Media coverage, donor interests and the aid business. Disasters, 27(2), 109-126. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-7717.00223

Orgeret, K. S. (2016). Cheap clothes: Distant disasters. Journalism turning suffering into practical action. Journalism, 19(7), 976-993. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884916671902

Otieno, K. (2006). Media Role in Disaster Risk Management. UNDP.

Oyanedel, R., & Alarcón, C. (2010). Refle xiones y desafíos: una mirada al tratamiento televisivo de la catástrofe [Reflections and challenges: a look at the televised coverage of the catastrophe]. Cuadernos. info, (26), 115-122. https://doi.org/10.7764/cdi.26.16

Panamerican Health Organization. (PAHO). (2011). Manual periodístico para la cobertura ética de las emergencias y los desastres [Journalistic manual for ethical coverage of emergencies and disasters]. https://www.paho.org/cor/index.php?option=com_docman&view=download&alias=229-manual-periodistico-para-la-cobertura-etica-emergencias-y-desastres&category_slug=desastres&Itemid=222

Parsons, S., Atkinson, P. M., Simperl, E., & Weal, M. (2015). Thematically analysing social network content during disasters through the lens of the disaster management lifecycle. In Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on World Wide Web (pp. 1221-1226). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/2740908.2741721

Pellegrini, S., Puente, S., & Grassau, D. (2015). La calidad periodística en caso de desastres naturales: cobertura televisiva de un terremoto en Chile. Estudios sobre el mensaje periodístico, 21, 249-267. https://doi.org/10.5209/rev_ESMP.2015.v21.50678

Pellegrini, S., Puente, S., Porath, W., Mujica, C., & Grassau, D. (2011). Valor Agregado Periodístico: la apuesta por la calidad de las noticias [Added Journalism Value: the commitment to the quality of news]. Ediciones UC.

Perry, R. W., Lindell, M. K., & Tierney, K. J. (Eds.). (2001). Facing the unexpected: Disaster preparedness and response in the United States. Joseph Henry Press.

Potter, D., & Ricchiardi, S. (2006). Cobertura de desastres y crisis [Disaster and crisis coverage]. International Center for Journalists.

Puente, S., Marín, H, Álvarez, P., Flores, P. M., & Grassau, D. (2019). Mental health and media links based on five essential elements to promote psychosocial support for victims: the case of the earthquake in Chile in 2010. Disasters, 43(3), 555-574. https://doi.org/10.1111/disa.12377

Puente, S., Pellegrini, S., & Grassau, D. (2013a). How to Measure Professional Journalistic Standards in Television News Coverage of Disasters? 27-F Earthquake in Chile. International Journal of Communication, 7, 1896-1911. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/2176/978

Puente, S., Pellegrini, S., & Grassau, D. (2013b). Journalistic challenges in television coverage of disasters: lessons from the February 27, 2010, earthquake in Chile. Communication and Society/Comunicación y Sociedad, XXVT(4), 103-125. https://dadun.unav.edu/bitstream/10171/35564/1/20131028154238.pdf

Quarantelli, E. L. (1996). Local mass media operations in disasters in the USA. Disaster Prevention and Management, 5(5), 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1108/09653569610131726

Quarantelli, E. L. (Ed.). (2005). What is a disaster? A dozen perspectives on the question. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203984833

Reporters Without Borders. (2005). Handbook for Journalists. Unesco. http://www.unesco.org/new/es/communication-and-informa-tion/resources/publications-and-communication-materials/pub-lications/full-list/handbook-for-journalists/

Ross, S. (2004). Toward new understandings: Journalists & humanitarian relief coverage. Fritz Institute. http://www.fritzinstitute.org/PDFs/ Case-Studies/Media_study_wAppendices.pdf

Scanlon, J. (2011). Research about the mass media and disaster: Never (well hardly ever) the twain shall meet. In J. Detrani (Ed.), Journalism Theory and Practice (pp. 233-269). Apple Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1201/b13161-12

Silverman, C. (Ed.). (2014). Verification handbook: An ultimate guideline on digital age sourcing for emergency coverage. European Journalism Centre. https://verificationhandbook.com/downloads/ver-ification.handbook.pdf

Small World News. (2012). Guide to Safely Using SatPh ones. Versión 1.0. https://smallworldnews.com/guides/satphone

Smeltzer, L., & Suchan, J. (1991). Guest editorial: Theory Building and Relevance, Journal of Business Communication, 28(3, Summer 1991), 181-186. https://doi.org/10.1177/002194369102800301

Smyth, F. (2012). Manual de seguridad para periodistas [Journalist Security Guide]. Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ). https://cpj.org/security/guide_es.pdf

Stolzenburg, K. (2007). Regional Perspectives on Digital Disaster Management in Latin America and the Caribbean. Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean - Project Documents Collection, 128. United Nations. https://repositorio.cepal.org/handle/11362/3552

Sutton, R. I., & Staw, B. M. (1995). What Theory Is Not. Administrative Science Quarterly, 40(3), 371-384. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393788

Swindell, C., & Hertog, J. (2012). Dimensions of emergency messages as perceived by journalists and sources. Public Relations Journal, 6(1), 1-21. https://prjournal.instituteforpr.org/wp-content/uploads/2012SwindellHertog.pdf

Tahir, B. A. (2009) Practical guide: Tips for conflict reporting. Intermedia.

The News Manual Online. (n.d.). Reporting death & disaster. In The News Manual. Volume 2: Advanced reporting. https://www.thenewsmanual.net/Manuals%20Volume%202/volume2_43.htm

Toledano, S., & Ardèvol-Abreu, A. (2013). Los medios ante las catástrofes y crisis humanitarias: Propuestas para una función social del periodismo [Role of the media in disasters and humanitarian crisis: proposals for a social function of journalism]. Communication & Society/Comunicación y Sociedad, 26(3), 190-213. http://hdl.handle.net/10171/35516

Ulloa, F. (2011). Manual de gestión de riesgos de desastre para comunicadores sociales [Disaster risk management handbook for social communicators]. UNESCO.

United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. (UNISDR). (2014). Annual Report 2014. http://www.unisdr.org/files/42667_unisdrannualreport2014.pdf

Valenzuela, S., Puente, S., & Flores, P. (2017). Comparing Disaster News on Twitter and Television: An Intermedia Agenda Setting Perspective. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 61(4), 615-637. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2017.1344673

Veil, S. R. (2012). Clearing the air: Journalists and emergency managers discuss disaster response. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 40(3), 289-306. https://doi.org/10.1080/00909882.2012.679672

Veil, S. R., Reynolds, B., Sellnow, T. L., & Seeger, M. W. (2008). CERC as a theoretical framework for research and practice. Health Promotion Practice, 9(4), 26-34. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839908322113

Whetten, D. A. (1989). What Constitutes a Theoretical Contribution? Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 490-495. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1989.4308371

Wilkins, L. (2010). Mitigation watchdogs: The ethical foundation for a journalist's role. In C. Meyres (Ed.), Journalism ethics: A philosophical approach (pp. 311-324). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195370805.003.0021

Wilkins, L. (2016). Affirmative Duties: The institutional and individual capabilities required in disaster coverage. Journalism Studies, 17(2), 216-230. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2014.974985

Yez, L. (2013). Desafíos éticos de la cobertura televisiva de un hecho traumático [Ethical Challenges on Television Coverage of a Traumatic Event]. Cuadernos.info, (32), 39-46. https://doi.org/10.7764/cdi.32.494

Zelizer, B., & Allan, S. (Eds.). (2011). Journalism after September 11 (2nd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203818961