|

Artículos The Making of a Modern Newspaper:

|

Oscar Aponte1.

1 ![]() 0000-0003-0991-4581 The Graduate

Center, City University of New York. oaponte@gradcenter.cuny.edu

0000-0003-0991-4581 The Graduate

Center, City University of New York. oaponte@gradcenter.cuny.edu

Recibido: 23/02/2019

Enviado a pares: 18/03/2019

Aprobado por pares: 30/05/2019

Aceptado: 10/06/2019

Para citar este artículo / to reference this article / para citar este artigo Aponte, O. (2019). The making of a modern newspaper: El Tiempo in Colombia, 1911–1940. Palabra Clave, 22(4), 1073-1098. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5294/pacla.2019.22.4.4

|

Abstract In this article I examine the first three decades of operation of the Colombian newspaper El Tiempo as a critical moment to understand the influential position the newspaper held in the country during a large portion of the twentieth century. In particular, I analyze the history of El Tiempo as a business, a topic usually unexplored by the history of the press and the public sphere in Colombia. In the first part, I explore the revenue and expenses of El Tiempo. I argue that facing the imported paper crisis generated by World War I, El Tiempo developed an effective commercial strategy that led the newspaper to become financially independent. In the second part, I analyze the internal organization of El Tiempo and the state of journalism as a profession in Colombia. I argue that the rationalization of tasks and the creation of a workers’ union at El Tiempo anticipated some aspects of what would characterize the professionalization of national journalism. In the third part, I explore the printing technologies and means of transportation used by El Tiempo to print and distribute newspaper issues. I argue that faster printing technologies and means of transportation enabled El Tiempo to expand its format and enlarge its circulation. In the conclusion, I suggest that the modernization of the press in Colombia led by El Tiempo had as a particularity that newspapers became modern while being the organ of a political party, in contrast to other Latin American countries where modern newspaper were independent from political parties. Keywords (Source Unesco Thesaurus): Colombia; newspapers; journalism; advertising; press advertising; advertising printing machines; printing workshops. |

Resumen En el presente artículo examino las tres primeras décadas de funcionamiento del periódico El Tiempo como momento crítico para entender la posición influyente del periódico en el país durante gran parte del siglo XX. En particular, analizo la historia de El Tiempo como negocio, un tema que, en términos generales, no ha sido explorado por la historia de la prensa y la esfera pública en Colombia. En la primera parte, exploro los ingresos y gastos de El Tiempo. Argumento que, ante la crisis de la importación de papel generada por la Primera Guerra Mundial, El Tiempo desarrolló una estrategia comercial efectiva que llevó al periódico a convertirse en financieramente independiente. En la segunda parte, analizo la organización interna de El Tiempo y el estado del periodismo como profesión en Colombia. Sostengo que la racionalización de tareas y la creación de un sindicato de trabajadores en El Tiempo anticiparon algunos aspectos de lo que caracterizaría la profesionalización del periodismo nacional. En la tercera parte, exploro las tecnologías de impresión y los medios de transporte utilizados por El Tiempo para imprimir y distribuir las ediciones del periódico. Argumento que la mayor rapidez de las tecnologías de impresión y de los medios de transporte le permitió a El Tiempo ampliar su formato y aumentar su circulación. A modo de conclusión, sugiero que la modernización de la prensa en Colombia liderada por El Tiempo tuvo como particularidad el hecho de que los periódicos se modernizaron, a la vez que siguieron siendo el órgano de un partido político, a diferencia de otros países latinoamericanos donde los periódicos modernos eran independientes de los partidos políticos. Palabras clave (Fuente tesauro de la Unesco): Colombia; periódico; periodismo; publicidad; publicidad periodística; máquina impresora de publicidad; imprenta. |

Resumo Neste artigo, analiso as primeiras três décadas do jornal El Tiempo como um momento crítico para compreender a posição influente do jornal no país durante grande parte do século XX. Em particular, analiso a história de El Tiempo como negócio, uma questão que, em termos gerais, não tem sido explorada pela história da imprensa e a esfera pública na Colômbia. Na primeira parte, exploro as receitas e despesas do El Tiempo. Argumento que, diante da crise na importação de papel gerada pela Primeira Guerra Mundial, El Tiempo desenvolveu uma estratégia comercial eficaz que levou o jornal a se tornar financeiramente independente. Na segunda parte, analiso a organização interna de El Tiempo e o estado do jornalismo como profissão na Colômbia. Argumento que a racionalização de tarefas e a criação de um sindicato de trabalhadores em El Tiempo anteciparam alguns aspectos do que caracterizaria a profissionalização do jornalismo nacional. Na terceira parte, exploro as tecnologias de impressão e os meios de transporte utilizados por El Tiempo para imprimir e distribuir as edições do jornal. Argumento que as tecnologias de impressão e meios de transporte mais rápidos permitiram a El Tiempo expandir seu formato e acrescentar sua circulação. Para concluir, sugiro que a modernização da imprensa colombiana liderada por El Tiempo teve, como particularidade, o fato de os jornais terem sido modernizados, ao mesmo tempo em que mantiveram-se em órgão de um partido político, ao contrário de outros países latino-americanos onde os jornais modernos eram independentes dos partidos políticos. Palavras-chave (Fonte tesauro da Unesco): Colômbia; jornal; jornalismo; publicidade; publicidade jornalística; impressora de publicidade; impressão. |

After a brief job interview with Eduardo Santos in 1925, young journalist—and later President of Colombia—Alberto Lleras (1958–1962) joined El Tiempo, which, in his opinion, was the most influential newspaper in the country in the 1920s. In his memoir, Lleras (2006) would recall “the thundering roar of the press,” the “army of workers” who with “leather aprons handled the type,” and “the large room with the 6 or 7 linotypes that El Tiempo had at the time” (p. 218, author’s translation). Aside from the impressive facilities and technology, Lleras highlighted that his monthly salary went up to COP 60 (sixty Colombian pesos), a salary that La República and El Espectador, where Lleras had previously worked, could not afford to pay him (Lleras, 2006, pp. 216–217). In fact, journalists based in Bogotá regarded El Tiempo as the best place to work, both for the newspaper’s political influence and for its resources.

This opinion about El Tiempo was shared not only by journalists and politicians across the country but also by historians of twentieth-century Colombia. How did El Tiempo achieve such a position among Colombian newspapers and hold it for such a large portion of the twentieth century? In this article, I explore the history of the first years of operation of El Tiempo as a critical moment for understanding the subsequent influential position of the newspaper. While most of the historiography about the press in Colombia underscores the political role played by El Tiempo and other newspapers, I will focus on El Tiempo as a business, analyzing its finances, internal organization, and use of technology.

Historians studying the press in Colombia have focused primarily on its political role because, as Eduardo Posada-Carbó (2010, p. 942) argues, newspapers in the country from the nineteenth century onwards were used fundamentally as political tools. Although political goals remained central, newspapers in early twentieth-century Colombia were changing in a number of directions. According to Ricardo Arias (2007, p. 93) and Isidro Vanegas (2011, p. 226) the quality of the information increased, the topics covered diversified, the reading public expanded, the administration and internal organization of the companies improved. Moreover, Colombian newspapers adopted the commercial strategies and technological innovations of the modern press in this time period. In short, they were moving towards a commercially-oriented model of journalism. As these changes have not been explored in depth in the Colombian case for the first decades of the twentieth century, in this article I intend to fill this gap in the historiography by showing that El Tiempo’s recognition well into the twentieth century should be explained considering how this newspaper became a financially independent and internally organized company employing state-of-the art printing and transportation technologies.

Financial Independence

When Alfonso Villegas founded El Tiempo on January 30, 1911, the lawyer and journalist had the goal of establishing a newspaper that would serve as the organ for the newly-created Republican Party, founded in 1909. A four-page long publication, it contained chiefly political analysis and opinions supporting the ideas and candidates of the Republican Party—whose members in Colombia and abroad were its targeted reading public as well as its most assiduous supporters—and had little room for advertisements. In this regard, El Tiempo shared traits that were common for the press in the country since the nineteenth century: These were newspapers that served primarily as political tools. They depended financially on the fortune of their owners, the government, the Catholic church, or the political parties whose views they represented. Their reading public was also limited. As long as newspapers fulfilled their role serving as party organs, launching candidates, and mobilizing voters, profitability was not usually a factor considered by newspaper owners (Posada-Carbó, 2010, p. 939).

In 1912, Eduardo Santos, a habitual contributor to El Tiempo and who years later would be elected President of Colombia (1938–1942), bought the newspaper for COP 5,000 and became its new editor-in-chief (Santos, 1955, p. 223). Although defending the ideas and promoting the candidates of the Republican Party remained one of Santos’ primary goals, the new editor-in-chief also considered it necessary to provide El Tiempo with a coherent financial and journalistic project that ensured both a stable source of revenue and quality information for its readers. After assuming the position as editor-in-chief, Santos announced his plan to El Tiempo readers: a larger newspaper with more pages to present the most comprehensive information possible of international and national matters, as well as to discuss business, science, and literature along with politics (El Tiempo, 1914, May 2).

During his first months as editor-in-chief, Santos was able to advance some of these goals—for instance, the amount of international news and the number of advertisements increased. Yet, with the outbreak of World War I in 1914, his journalistic project faced increasing difficulties. The war affected the supply of international news, as cable communication from Europe failed and European governments imposed censorship on war correspondents and international cables. As a result, El Tiempo frequently communicated to its readers that no information had been received from Europe or denounced that the information obtained through those means was not reliable. The drastic increase in the price of imported newsprint, however, was the most compelling challenge faced by El Tiempo during the war years. Newsprint paper was imported from Europe and the United States, as El Tiempo informed its readers early in 1917, and prices had increased from 1914 to 1917 by almost 300% (El Tiempo, 1917, February 24). In 1916, imports of paper and paper products into Colombia were valued at COP 913,502, while one year later imports decreased to 710,690. By 1918, there was a shortage of paper everywhere in the country (Bell, 1921, p. 371).1

Facing a newsprint paper shortage and increasing import prices during World War I, most of the newspapers in Colombia decided to increase the price of street sales and subscriptions. By 1917, El Nuevo Tiempo, a Conservative newspaper published in Bogotá, increased street sales prices from COP 0.03 to 0.05 and annual subscriptions from COP 7 to 12. Even newspapers in the port city of Barranquilla had to increase sale prices, notwithstanding that they had cheaper and easier access to imported paper since they did not have to transport it along the Magdalena River. The strategy adopted by El Tiempo to face the paper crisis was different: The newspaper opted to keep the prices for street sales and subscriptions unchanged while increasing advertising prices in the same proportion as the price for imported newsprint had increased. Although El Tiempo finally had to increase sales prices by the end of 1919, throughout the four years of the war street sales prices remained at COP 0.03 a copy and annual subscriptions at COP 7. By contrast, advertising prices increased by 300% during the war.

With this strategy, El Tiempo not only expected to ensure a stable source of revenue but also to retain El Tiempo’s readership and circulation across the country, as well as to endorse the expansion of the still meager reading public in Colombia. According to El Tiempo, companies contracting press advertising services should be the first to support lower street sales and subscription prices. This is because only low prices ensured that newspapers were broadly read and guaranteed that advertisements reached a larger number of potential clients (El Tiempo, 1919, July 25). Even though the expansion of El Tiempo’s format promised by Eduardo Santos had to wait until the 1920s, the decision to increase advertising revenue rather than the newspaper’s sales price became the commercial strategy that helped El Tiempo to weather the hardships imposed by World War I and, in the long term, to achieve financial independence.

Although detailed information of El Tiempo’s revenue and expenses is only available until 1919, the information I provide in Table 1 suggests that El Tiempo’s financial model changed in this time period. In 1912, El Tiempo depended heavily on subscriptions, which accounted for up to 52.17% of total revenues in 1914. These subscribers were typically members of the Republican Party, and most of them lived outside Bogotá. For instance, in June 1913, 746 out of El Tiempo’s 1,081 subscribers lived in other parts of Colombia or abroad, while only 335 lived in the city of Bogotá (“Libros de cuentas de El Tiempo,” 1912–1919, f. 217). Besides, most of the issues sent to cities other than Bogotá were sold through agencies and distributed by members of the Republican Party.2 Although I do not have access to detailed figures about El Tiempo’s circulation and number of subscribers during the 1910s, the fact that the percentage of revenues accounted for by subscriptions declined somewhat over the years analyzed should not be taken to mean that the composition of the newspapers subscribers remained static. In fact, as the number of readers expanded, El Tiempo came to rely less on members of the Republican Party for its circulation growth. Nor should we assume that net revenue accounted for by subscriptions did not increase. In 1912, the revenue from subscriptions was COP 353.37, while in 1919 it was COP 12,508.66.3

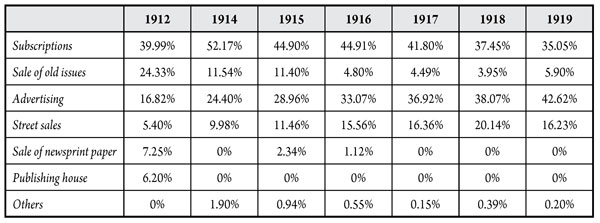

Table 1. Annual revenue of El Tiempo from 1912 to 1919 (percentages)*

* I calculated these figures based on the

account books of El Tiempo from 1912 to 1919. The

figures for 1913 are not available at the archive.

Source: “Libros de cuentas de El Tiempo,” 1912–1919, ff. 216–219.

The information I provide in Table 1 shows that revenue derived from advertising increased steadily over the 1910s: While in 1912 it accounted for 16.82% of the newspaper’s revenue, by 1919 it accounted for 46.62%. Likewise, street sales increased from 5.40% in 1912 to 16.23% in 1919. Moreover, income from old newspaper issues, that is, issues sold after the day on which they were printed, decreased as, over the years examined here, El Tiempo increased its ability to sell all of its issues on the same day they were printed. Indeed, revenue from the sale of old newspaper issues decreased from 24.33% in 1912 to 5.90% in 1919. Finally, as El Tiempo increased its annual revenue and exploited its paper and printing machines more efficiently and intensively, the revenue accounted for by sale of newsprint paper and publishing house services also decreased. The former decreased from 7.25% in 1912 to 0% in 1919—also due to the paper crisis described above—and the latter decreased from 6.20% in 1912 to 0% in 1919.

In brief, by 1919 El Tiempo did not depend financially on the personal fortune of Eduardo Santos, the government, or the Republican Party. On the contrary, El Tiempo was a financially independent newspaper whose revenue came from the sale of newspaper issues, subscriptions, and above all, from advertising. However, the growth of advertising revenue was not simply the result of decisions made by Eduardo Santos. Rather, what made it possible for El Tiempo to rely financially on advertising was a shift in Colombia’s economic circumstances that encouraged national and foreign companies to expand their markets and increase the number of their clients. The advertising services provided by El Tiempo and other newspapers proved critical to that endeavor. As Marco Palacios (1979, p. 285) and Jesús Bejarano (1994, pp. 17–22) have shown, the expansion of coffee production and exports in the early twentieth century propelled economic growth, production diversification, and the strengthening of the internal market, resulting in a dynamic and growing national economy. This new economic situation transformed the press business in the country. According to Christopher Abel (1987, pp. 50–51), the country’s economic prosperity resulting from rising coffee exports enabled the press to find solid financial support in commercial advertising.

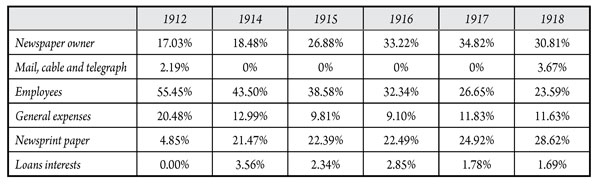

El Tiempo’s annual revenue increased exponentially—while in 1912 it was COP 8,198.57, in 1922 it rose to a peak of COP 106,804.16, and then declined somewhat in 1925 to COP 99,520.54.4 As a consequence of the growing revenue of El Tiempo, expenses over the same years not only increased but also diversified. As I show in Table 2, El Tiempo’s annual expenses reflect the newspaper’s improving financial situation. In 1912, general expenses and labor costs accounted for 20.48% and 55.45% of the newspaper ’s expenses, respectively. Even as the number of El Tiempo’s employees increased, as did general expenses, such as the cost of leasing facilities, in 1918 general expenses and employee salaries decreased as a proportion of the newspaper’s total expenses to 11.63% and 23.59%, respectively. Expenses for newsprint paper increased from 4.85% in 1912 to 28.62% in 1918, not only due to the imported paper crisis described above, but also because the circulation figures of El Tiempo grew. Likewise, while expenses for mail, telegraph, and cable services accounted for 2.19% of total expenses in 1912 and declined to almost 0% during the years of World War I, by 1918 they had increased to 3.67%. Finally, the revenue accruing to El Tiempo’s owner also increased—from 17.03% in 1912 to 30.81% in 1918. The growing income of El Tiempo thus made it possible to fulfill the expansion project that Eduardo Santos had articulated in 1914 as the newspaper had more revenue from which to draw to buy more paper, increase the cable and telegraph services it contracted, and hire more employees.

Table 2. Annual expenses of El Tiempo from 1912 to 1918 (percentages)*

* I calculated these figures based on the

account books of El Tiempo from 1912 to 1919. The

figures for 1913 are not available at the archive and I did not include 1919

because for that year expenses are classified in other categories.

Source: “Libros

de cuentas de El Tiempo,” (1912–1919, ff. 216–290).

Financial independence, however, did not equate with political autonomy. In fact, newspapers in Colombia stand out in Latin America because they continued to be organs of a political party during a large portion of the twentieth century, even as publications like El Tiempo achieved financial independence. Towards the end of the 1920s, when El Tiempo shifted its political allegiance from the Republican to the Liberal Party, the newspaper had become the platform of its second editor-in-chief, Eduardo Santos, and the moderate wing he defended within the Liberal Party. By contrast, in Argentina, La Prensa led the process by which journalism was established as a profession separate and independent from the government and the political parties (Saítta, 2010, p. 30), and in Mexico, it was the state-financed newspaper El Imparcial that led the modernization of the press (Piccato, 2016, pp. 7–8).

Internal Organization

After the war ended, Eduardo Santos was finally able to expand the format of the newspaper as promised. In contrast with the 4- and 6-page issues the newspaper printed during the 1910s, in the 1920s regular issues were 8- to- 12 pages long and extraordinary issues were even longer.5 Yet Eduardo Santos did not manage to transform El Tiempo into Colombia’s most influential newspaper all on his own. As the company grew and the circulation and format of the publication expanded, Eduardo Santos brought together a robust editorial and administrative team to look after different aspects of the newspaper. The first step was appointing Fabio Restrepo as the Chief Financial Officer of the newspaper. With Restrepo in charge of business and commercial operations, such as the purchase of paper and printing machines, Eduardo Santos as the Publisher and Editor-in-Chief was in a position to focus on the elaboration of the newspaper’s editorial line. Then, Enrique Santos, Eduardo Santos’ brother and one of the most broadly read columnists in Colombia at the time, was appointed as Deputy Managing Editor, a position that Enrique Santos held until 1930, when he was promoted to Managing Editor and Alberto Lleras took over as Deputy Managing Editor. Additionally, when El Tiempo began publishing pages dedicated to particular topics, section editors were hired as well. That was the case of the judicial page, the sports page, and the cinema page.

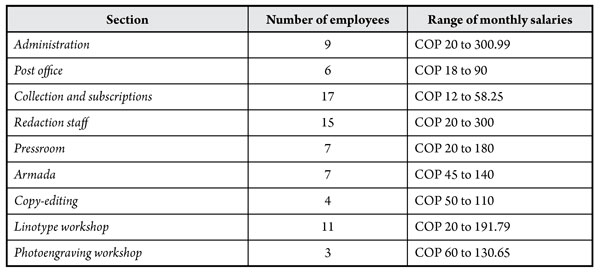

As Marianne Salcetti (1995) has argued, increased speed in newspaper production and the expansion of newspaper format produces division and specialization of labor not only within the editorial team but also among journalists and workers (pp. 59–60). This was the case in El Tiempo, whose employees had as a major concern that all responsibilities and tasks be clearly assigned and their work be more standardized. In a letter addressed to Eduardo Santos in 1933, the employees requested the editor-in-chief to establish a written regulation imbued “with the force of law inside the company,” with the goal of “designing and distributing responsibilities” among employees (Federación de Empleados de la Prensa de Bogotá, 1931, f. 313, author’s translation). As I show in Table 3, by 1931 El Tiempo had a total of 79 employees organized in 9 different sections: administration, with 9 employees under the direction of Fabio Restrepo; the editorial and reporting staff, encompassing the 15 journalists working for El Tiempo; the copy-editing section, with 4 employees in charge of proofreading the articles written by journalists; the armada section, with 7 employees in charge of putting together articles, advertisements, and pictures in the paper before it was sent to the pressroom; the pressroom, with 7 employees; linotype workshop, with 11 employees; photoengraving workshop, with 3 employees; collection and subscriptions, with 17 employees; and the post office, with 6 employees.

Table 3. El Tiempo’s employees and salaries in 1931

Source: “Nómina de empleados” (1931).

Among journalists, tasks were also distributed. The team of journalists at the newspaper was organized in three different sections: editorial, news department, and special pages. The editorial section, under the direction of Eduardo Santos, involved three assistants in charge of the editorial page of El Tiempo. The news department encompassed journalists collecting national information and local news from Bogotá, as well as international information collected through cable services, contracts with international news agencies such as the United Press, news from international correspondents, and diplomatic reports (“Plan orgánico de El Tiempo,” n.d., f. 17). The special pages section comprised journalists specialized in sports, judicial topics, cinema, among others. Every journalist was assigned a number of institutions and places where he would have to go on a daily basis in order to look for news. In this fashion, El Tiempo’s journalists were in charge of collecting information from Ministries, the Senate and the House of Representatives, the Bogotá City Hall, the Colombian Coffee Growers Federation, the Banking Federation, the Supreme Court, the Fire Department, the Catholic Church, among others (“Distribución de trabajo,” n.d., f. 352).

In 1931, employees from El Espectador and El Tiempo, the two most influential publications in the country at the time, came together to found the Union of the Employees of the Press in Bogotá, which turned into the Federation of Press Workers of Bogotá after employees from almost every newspaper in the city requested to join. By the end of 1931, the Federation had over 200 members in Bogotá. Since improving the living standards of the employees of the press was one of its major goals, the Federation presented contract proposals to all the newspapers in Bogotá. In the case of El Tiempo, the Federation requested from the company: paid Sunday rest; an 8-hour working day; 15 annual days of paid vacation; retirement after 15 years of work in the company; sanitation improvements in the facilities, particularly in the pressroom; among other demands (Federación de Empleados de la Prensa de Bogotá, 1931, ff. 299–314). The Federation requested that El Tiempo adopt the working conditions that similar companies had already implemented, despite not having the same status or economic resources of El Tiempo (Federación de Empleados de la Prensa de Bogotá, 1931, f. 313). In addition, the Federation demanded to be recognized as the representative organization of El Tiempo’s employees, since it remained committed to guarding “the harmony between employer and employees” (Federación de Empleados de la Prensa de Bogotá, 1931, f. 299, author’s translation). Eduardo Santos celebrated the foundation of the union, which he regarded as a fundamental tool to “facilitate the relations between the management and the employees of El Tiempo” (Santos, 1934, f. 197, author’s translation). By 1934, the Federation had 52 members at El Tiempo (Sindicato de Trabajadores de El Tiempo, 1934, f. 149).

Historians analyzing journalism in Colombia have debated about the professionalization of journalism in the country in the first decades of the twentieth century. In fact, some of the components that Christophe Charle (2004, pp. 143–155) identified to explain the professionalization of journalism in France—the division of labor and the foundation of unions—were present, while others—the separation from other professions such as lawyer, professor, and politician; higher salaries; and the material conditions for journalism to be a full-time job—were still missing in Colombia. Low salaries were undoubtedly the most compelling obstacle for the professionalization of journalism in the country. As I show in Table 3, the range of salaries that journalists at El Tiempo received varied greatly. While renowned journalists such as Alberto Lleras and Oliverio Perry received monthly salaries of COP 300 and COP 275 respectively, almost half of El Tiempo’s journalists received less than COP 100 a month with Margarita Gonzalez on the bottom rung of the pay scale at COP 20. That was also the case in other sections. While one of the administrators, José Fernández, received a monthly salary of COP 300.99, Emma Torres and Guillermo Santos received COP 50 and COP 20, respectively (“Nómina de empleados,” 1931). Thus, for most of El Tiempo’s employees, journalism could not have been a full-time job.

Yet even those receiving higher salaries practiced journalism alongside other professions. According to Eduardo Posada-Carbó (2010, p. 949), in early twentieth-century Colombia, there was no sharp division of labor between journalists and politicians. A good reputation as a journalist usually led to a career in politics, as proven by the number of presidents who attained high rank as journalists, as well as the number of active political journalists who became members of presidential cabinets or were elected to Congress. In addition, up until the 1930s, there was no professional training for journalists in the country. The first journalism training courses in Colombia were offered by the Javeriana University’s School of Philosophy and Letters in 1936, and the first School of Journalism was founded in the same university in 1949 (Facultad de Comunicación y Lenguaje, Universidad Javeriana, 2014, p. 1).

Printing Machines and Transportation

The first edition of El Tiempo in January 1911 printed just 150 copies. Not only did the newspaper not have a large reading public, the antiquated nature of its printing presses constituted a major obstacle to increasing circulation. By the turn of the twentieth century, printing a newspaper in Colombia was a slow and expensive process involving technology not easily obtainable in the country. During its first months of operation in 1911, El Tiempo did not have printing presses of its own and had to use the facilities of Gaceta Republicana to print its issues. In June 1911, El Tiempo bought the first printing press the newspaper ever owned—an old, basic press without a linotype. A maximum of 1,200 copies of 4 pages could be printed per hour with this machine (El Tiempo, 1961, January 30). However, the situation changed in 1919 when the newspaper acquired a Duplex rotatory printing press and a linotype workshop, both of which enabled a faster composition and printing process (El Tiempo, 1919, July 25, p. 1). The first newspaper that brought a rotatory printing press to Colombia was El Diario Nacional in 1915; by the end of the 1920s, the most important newspapers across the country had acquired printing presses of their own.

In 1926, El Tiempo revolutionized the printing and publishing industry in Colombia by bringing state-of-the-art technology in order to print a daily edition of 16 pages (El Tiempo, 1926, January 1, p. 81). In fact, that year El Tiempo bought a 16-page capacity Duplex rotatory printing press and an 8-page capacity Duplex semi-rotative printing press, as well as a Linotype Ludlow machine—a typography system consisting of hot metal typesetting—and photoengraving and stereotype workshops.6 Most of this technology was bought from the Duplex Printing Company, an American company founded in Michigan in 1884, with which El Tiempo established an enduring commercial relationship. When in 1945 El Tiempo was about to purchase new printing presses, the newspaper received bids from three American companies: Goss, Hoe, and Duplex. Although El Tiempo recognized Goss’s and Hoe’s printing presses to be the best options available on the market, higher prices and a longer shipping time led El Tiempo once more to the Duplex Printing Company. While the Duplex machine was USD 90,000 and could be delivered to Bogotá by mid-1946, the Hoe and the Goss were priced at USD 114,920 and USD 120,000 and required a delivery time to Bogotá of 26 and 20 months, respectively (“Memorandum sobre prensas rotativas para el Doctor Santos,” 1945, f. 97). With the new and better technology provided by the Duplex printing press, El Tiempo was able to steadily increase its circulation over the following years.

In addition to printing technology, the use of modern means of transportation helped El Tiempo to enlarge and accelerate the newspaper’s circulation. The most compelling distribution challenge facing El Tiempo in the 1910s was whether the newspaper could be delivered the same day it was printed. Although that goal was shortly achieved in Bogotá, distribution outside the capital posed undeniable obstacles. By the 1910s, river navigation was the most efficient and commonly used means of transportation across Colombia, making the Magdalena River the principal highway into the interior of the country. However, it required eight days to a month for someone to travel from Bogotá to the Caribbean Coast. Likewise, imported merchandise critical for El Tiempo, such as paper and printing presses, did not reach Bogotá from Barranquilla in less than four or five months (Bell, 1921, p. 244). Railroads, on the other hand, were not convenient for El Tiempo since up to the 1920s they were mostly designed to connect coffee plantations with the Magdalena River.

Beginning in the 1930s, air transport allowed El Tiempo to deliver newspapers to points outside Bogotá on the same day the paper was printed. By plane, the trip from Bogotá to Barranquilla was shortened to 7 hours, which made El Tiempo available daily for readers in that city (El Tiempo, 1961, January 30, p. 15). In a letter addressed to Eduardo Santos in September 1935, El Tiempo’s Chief Financial Officer, Fabio Restrepo, provided a detailed description of the means of transportation used by El Tiempo to distribute its issues. Air transport was used to send the newspaper to Medellín and Barranquilla. Ground transportation on highways was used to send it to the departments of Cundinamarca and Santander. Railways were used to send El Tiempo to the department of Huila and to the cities of Girardot, Ibagué, Zipaquirá, and Facatativá. In Bogotá, El Tiempo depended on ground transportation to deliver the newspapers to subscribers and on voceadores—street hawkers or newsboys. Given the ample number of operations that El Tiempo demanded to be distributed, one of the major concerns Fabio Restrepo had was delivering in time the newspaper to the providers of each transportation and distribution service.7

Although the press had traditionally been read by a small public, mostly located in Bogotá, new transportation technologies—especially aviation—made newspapers available to a broader readership beyond the major cities. In fact, over the following years, air transport became the most important means of transportation for distributing El Tiempo. In 1940, a total of 215,821 kilograms of paper printed with El Tiempo’s issues were transported via air carrier, and by the 1960s, air transport accounted for 61% of the newspapers distributed outside Bogotá (El Tiempo, 1961, January 30, p. 15). Since the foundation of the Colombian-German Air Transport Company (SCADTA) in 1911—Latin America’s first airline—air transport of passengers, cargo, and post mail had been growing in Colombia. By 1940, a total of 53,357 passengers, 5,651,774 kilograms of cargo, and 82,439 kilograms of post mail traveled by air in the country (“Colombia en Cifras,” 1945, p. 142).

Besides new and improved printing and transportation technologies, El Tiempo’s circulation expanded as the topics covered diversified and new sections addressed to specific groups of readers were created. As it was the case in other countries from the nineteenth century onwards, in Colombia the expansion of the reading public involved the creation of sections and pages addressed to women and children.8 The women’s page of El Tiempo was printed for the first time in 1915. It presented information that the newspaper considered linked to roles traditionally assigned to women, that is, roles limited to the private space of the household—home care, beauty, fashion, clothing, child rearing, among others—whereas domestic and international politics as well as business were considered to be masculine subjects. The children’s section of El Tiempo was printed for the first time in 1927 as a response to the emergence of children as a new community of readers in Colombia. It presented information that the newspaper considered appropriate for children, such as games, pictures, and children’s literature.

In sum, thanks to new printing and distribution technologies, as well as to new topics and sections, El Tiempo was able to expand its circulation and reach a broader readership. Although circulation figures are not consistently available for the years under study, it is possible to get an idea of the evolution of El Tiempo’s circulation. While in January 1911 El Tiempo printed only 150 copies, in 1912 the newspaper printed 800 daily issues. By June 1913 the newspaper had a circulation of 1,700 copies, 746 of which went to subscribers outside Bogotá; 335 to subscribers in Bogotá; 226 to agencies operating in Colombia; 166 were sent to other newspapers and companies contracting advertising services with El Tiempo; 150 to street sales; and the remaining 72 were either held in reserve, in the archives or were damaged (“Libros de cuentas de El Tiempo,” 1912–1919, f. 217; Santos, 1955, p. 223). In 1931, the Colombian Government Ministry certified that El Tiempo printed on average 32,380 copies in April, with an extraordinary larger edition on April 11, a day on which the newspaper had a circulation of 59,426 (Martínez, 1931, ff. 1–2). In September 1935, El Tiempo’s Chief Financial Officer, Fabio Restrepo, informed that El Tiempo printed 27,000 daily copies on average (Restrepo, 1935, f. 169).9

Circulation figures remained low in comparison to other Latin American countries. However, as Eduardo Posada-Carbo (2010) argues, such figures do not reveal much about the patterns of readership. For instance, since early in the nineteenth century, newspapers reached a wider public via practices such as reading newspapers out loud—the latter being a common practice that enabled illiterate audiences to access newspapers. This was common in rural areas where the priest or local authorities would read selections from newspapers out loud in informal gatherings (Foreign Areas Studies Division, 1961, p. 187). It was common even in urban areas, where groups of illiterate workers would gather to listen to, and discuss, newspaper content (Núñez, 2006, p. 64). In fact, as Mary Roldán (n.d.) has shown, this link between written culture and oral tradition was to continue in the case of radioperiódicos—as announcers read newspapers over the microphone for radio audiences.

Conclusions

The first decades of the twentieth century represented decades of substantial transformation for El Tiempo. The newspaper went from being a four-page long publication dedicated to political writings with only a little room for advertisements and images in 1911, to becoming an eighteen-page long publication with broad coverage of both national and international news, as well as space for advertisements, photography, cartoons, and illustrations in 1940. Better financial conditions, as well as internal re-organization, faster printing presses, and improved means of transportation were key elements that facilitated these changes. After World War I, El Tiempo became a financially independent company whose revenue depended on the sale of its own issues, subscriptions, and above all, advertising. This enabled the paper to no longer require or depend on the financial support of its owner, the state, or a political party. As part of its modernization process, El Tiempo also engaged in an internal re-organization of the paper, dividing specific tasks to particular employees and assigning journalists to cover specific topics. Although journalism was still not a full-time profession in Colombia, the working and living conditions of journalists changed during this time period, in part in response to the growth of union representation. Finally, El Tiempo acquired state-of-the-art printing presses and linotype machines that enabled a faster printing and larger circulation of the newspaper.

As I mentioned at the start of this article, the wide-ranging political influence wielded by El Tiempo in Colombia during the twentieth century cannot be understood without taking into account the impact of new printing presses, the growth of paid advertising, and the rationalization of tasks within the newspaper. These changes were not limited to Colombia’s El Tiempo but representative of a worldwide transformation of the press since the late nineteenth century. As early as 1918, El Tiempo identified the main elements characterizing the trend of “modern” newspapers publishing around the world and sought to reproduce these at home. The creation of stable companies with steady sources of revenue separate from an owner or patron’s economic support, reporting focused on a detailed presentation of urban life, and the use of modern information technologies such as cable and the telegraph were among some of the features that El Tiempo assigned to modern newspapers (El Tiempo, 1918, June 17, p. 2). After a trip to Argentina in 1926, Alberto Lleras not only shared this notion of modern newspapers but also claimed that El Tiempo could take the lead in Colombia. For Lleras, El Tiempo had to fulfill the role that La Prensa had in Argentina, El Mercurio in Chile, El Sol in Madrid, and the New York Times in the United States (Lleras, 1929, f. 493). Lleras’s choice of newspapers to emulate was not haphazard—these were newspapers playing leading roles in the larger process of modernizing the press.

Despite the importance of such external influences in shaping domestic publishing, however, the modernization of the press in Colombia has to be studied keeping in mind local particularities as well. In contrast to other Latin American countries, in Colombia El Tiempo took the lead role in modernizing the press and was a financially independent company while being the organ of the Republican Party first, and from 1921, of the Liberal Party. Moreover, other Colombian newspapers that followed the path opened up by El Tiempo shared this characteristic. Historians have examined in depth the central political role that Colombian newspapers held in the nineteenth and twentieth century; yet the analysis of financial conditions, press advertising, printing presses, and the professionalization of journalism has only recently emerged as an avenue of historical research. Further scholarship regarding these topics will undoubtedly complicate our histories of the press and the public sphere in twentieth-century Colombia.

Notas

1 Prices and imports, however, did not stabilize immediately after the war was over. As late as 1922, El Tiempo on occasion had to borrow newsprint paper from the Colombian government, in particular, the National Store and the Ministry of Public Works (Belalcázar, 1922, f. 320).

2 The correspondence of Alfonso Villegas as Editor-in-Chief from 1911 to 1913 shows that most of El Tiempo readers, both in Colombia and abroad, were interested in the circulation of El Tiempo as long as it was the organ of the Republican Party (“Correspondencia de Alfonso Villegas,” 1911–1913, ff. 0580–1107).

3 Net revenue from subscriptions is expressed in 1912 constant prices (“Libros de cuentas de El Tiempo,” 1912–1919, ff. 216–290).

4 Annual revenue is expressed in 1912 constant prices (see “Libros de cuentas de El Tiempo,” 1912–1919, f. 259).

5 For instance, on November 21, 1922, El Tiempo printed a 40-page long issue to commemorate the end of the War of a Thousand Days, and on January 1, 1926, the extraordinary issue reached the record of 96 printed pages.

6 By 1936, El Tiempo’s photoengraving workshop printed annually 5,323 photoetched pictures measuring 690,317 square meters (“Balance del taller de fotograbado en los años 1935 y 1936,” n.d., f. 16).

7 In fact, El Tiempo’s Chief Financial Officer would design a detailed schedule to deliver the newspaper on time to the air transport company, ground transportation companies, railways companies, voceadores, among others (Restrepo, 1935, ff. 169–170).

8 In the case of nineteenth-century Europe, Martyn Lyons (1999) identifies three new groups of readers: women, children, and workers (pp. 313–315). Although El Tiempo did not create a section addressed to the working class, working-class-authored newspapers expanded in Colombia during the first decades of the twentieth century.

9 Similar figures were presented by Bolivian Ambassador Alcides Arguedas, who arrived in Colombia in 1929. According to Arguedas, in the 1930s El Tiempo had the largest circulation in the country ranging from 30,000 to 50,000 daily copies. Arguedas also presented the circulation figures for other Colombian newspapers: Mundo al día printed between 20,000 and 40,000; El Espectador printed 15,000; El Nuevo Tiempo printed 5,000; El Diario Nacional printed 4,000; and El Debate printed 3,000 (Arguedas, 1983, pp. 163–164).

References

Abel, C. (1987). Política, iglesia y partidos en Colombia. Bogotá, Colombia: FAES Universidad Nacional de Colombia.

Archivo digital de El Tiempo. Retrieved from https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=N2osnxbUuuUC

Arguedas, A. (1983). La danza de las sombras: apuntes sobre cosas, gentes y gentezuelas de la América Española. Bogotá, Colombia: Banco de la República.

Arias, R. (2007). Los Leopardos. Una historia intelectual de los años 1920. Bogotá, Colombia: ICANH & Facultad de Ciencias Sociales Universidad de los Andes.

Balance del taller de fotograbado en los años de 1935 y 1936. (n.d.). [Archivo Eduardo Santos, Fondo El Tiempo, Caja 6, Carpeta 1, f. 16]. Biblioteca Luis Ángel Arango, Bogotá, Colombia.

Bejarano, J. (1994). La economía. In J. Jaramillo (Series Ed.), Manual de historia de Colombia (4th ed., Vol. 3, pp. 17–79). Bogotá, Colombia: Procultura S.A. & Tercer Mundo Editores.

Belalcázar, R. (1922, March 15). [Letter addressed to Fabio Restrepo, Archivo Eduardo Santos, Fondo El Tiempo, Caja 3, Carpeta 6, f. 320]. Biblioteca Luis Ángel Arango, Bogotá, Colombia.

Bell, P. L. (1921). Colombia. A commercial and industrial handbook. Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office.

Charle, C. (2004). Le siècle de la presse (1830–1939). Paris, France: Éditions du Seuil.

Correspondencia de Alfonso Villegas. (1911–1913). [Archivo Eduardo Santos, fondo El Tiempo, Caja 8, Carpetas 4–6, ff. 0580–1107]. Biblioteca Luis Ángel Arango, Bogotá, Colombia.

Colombia en Cifras. (1945). Bogotá, Colombia: Librería Colombiana Camacho Roldán.

Distribución de trabajo. (n.d.). [Archivo Eduardo Santos, fondo El Tiempo, Caja 5, Carpeta 4, ff. 351–352]. Biblioteca Luis Ángel Arango, Bogotá, Colombia.

El Tiempo. (1914, May 2). Retrieved from https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=N2osnxbUuuUC&dat=19140502&printsec=frontpage&hl=es

El Tiempo. (1917, February 24). Retrieved from https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=N2osnxbUuuUC&dat=19170224&printsec=frontpage&hl=en

El Tiempo. (1918, June 17). Retrieved from https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=N2osnxbUuuUC&dat=19180617&printsec=frontpage&hl=en

El Tiempo. (1919, July 25). Retrieved from https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=N2osnxbUuuUC&dat=19190725&printsec=frontpage&hl=en

El Tiempo. (1926, January 1). Retrieved from https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=N2osnxbUuuUC&dat=19260101&printsec=frontpage&hl=en

El Tiempo. (1961, January 30). Retrieved from https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=N2osnxbUuuUC&dat=19600130&printsec=frontpage&hl=en

Facultad de Comunicación y Lenguaje, Universidad Javeriana. (2014). Reseña histórica Facultad de Comunicación y Lenguaje. Retrieved from https://comunicacionylenguaje.javeriana.edu.co/documents/3277755/3278891/Reseña+histórica+Facultad+de+Comunicación+y+Lenguaje.pdf/cd643261-0bd9-4cff-b9d8-e8773d497d66

Federación de Empleados de la Prensa de Bogotá. (1931, October 15). [Letter addressed to Eduardo Santos, Archivo Eduardo Santos, fondo El Tiempo, Caja 5, Carpeta 4, ff. 299–314]. Biblioteca Luis Ángel Arango, Bogotá, Colombia.

Foreign Areas Studies Division. (1961). Special warfare. Area handbook for Colombia. Washington D.C.: Department of the Army.

Libros de cuentas de El Tiempo. (1912–1919). [Archivo Eduardo Santos, Fondo El Tiempo, Caja 7, Carpeta 3, ff. 216–290]. Biblioteca Luis Ángel Arango, Bogotá, Colombia.

Lleras, A. (1929, April 5). [Letter addressed to Eduardo Santos, Archivo Eduardo Santos, Fondo Correspondencia Personajes, Caja 9, Carpeta 7, ff. 492–495]. Biblioteca Luis Ángel Arango, Bogotá, Colombia.

Lleras, A. (2006). Memorias. Bogotá, Colombia: El Ancora Editores & Taurus.

Lyons, M. (1999). New readers in the nineteenth century: Women, children, workers. In G. Cavallo & R. Chartier (Eds.), A history of reading in the west (pp. 313–344). Amherst, Germany: University of Massachusetts Press.

Martínez, M. (1931, May 12). [Letter addressed to Fabio Restrepo, Archivo Eduardo Santos, Fondo El Tiempo, Caja 6, Carpeta 1, ff. 1–2]. Biblioteca Luis Ángel Arango, Bogotá, Colombia.

Memorandum sobre prensas rotativas para el Doctor Santos. (1945, December 12). [Archivo Eduardo Santos, Fondo El Tiempo, Caja 5, Carpeta 3, f. 97]. Biblioteca Luis Ángel Arango, Bogotá, Colombia.

Nómina de empleados (sueldos mensuales) y promedio mensual en tres meses de los que trabajan por porcentaje. (1931, May 25). [Archivo Eduardo Santos, Fondo El Tiempo, Caja 5, Carpeta 5]. Biblioteca Luis Ángel Arango, Bogotá, Colombia.

Núñez, L. (2006). El obrero ilustrado. Prensa obrera y popular en Colombia, 1909–1929. Bogotá, Colombia: Ediciones Uniandes.

Palacios, M. (1979). El café en Colombia (1850–-1970). Bogotá, Colombia: FAES.

Piccato, P. (2016). The public sphere and liberalism in Mexico: From the mid-19th century to the 1930s. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Latin American History. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199366439.013.266

Plan orgánico de El Tiempo. (n.d.). [Archivo Eduardo Santos, fondo El Tiempo, Caja 6, Carpeta 1, f. 17]. Biblioteca Luis Ángel Arango, Bogotá, Colombia.

Posada-Carbó, E. (2010). Newspapers, politics, and elections in Colombia, 1830–1930. The Historical Journal, 53(4), 939–962. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0018246X1000049X

Restrepo, F. (1935, September 4). [Letter addressed to Eduardo Santos, Archivo Eduardo Santos, Fondo El Tiempo, Caja 5, Carpeta 2, ff. 169–170]. Biblioteca Luis Ángel Arango, Bogotá, Colombia.

Roldán, M. (n.d.). Civic mediations: News radio, urban life, and the politics of the public access in Colombia. Unpublished manuscript.

Saítta, S. (2010). Regueros de tinta. El diario CRITICA en la década de 1920. Buenos Aires, Argentina: Editorial Sudamericana.

Salcetti, M. (1995). The emergence of the reporter: Mechanization and the devaluation of editorial workers. In H. Hardt & B. Brennen (Eds.), Newsworkers: Towards a history of the rank and file. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Santos, E. (1934, August 20). [Letter addressed to Fernando Vega Escobar, Archivo Eduardo Santos, fondo El Tiempo, Caja 5, Carpeta 4, ff. 197–198]. Biblioteca Luis Ángel Arango, Bogotá, Colombia.

Santos, E. (1955). La crisis de la democracia en Colombia y “El Tiempo.” Bogotá, Colombia: Gráfica Panamericana.

Sindicato de Trabajadores de El Tiempo. (1934, November 12). [Letter addressed to Eduardo Santos, Archivo Eduardo Santos, Fondo El Tiempo, Caja 5, Carpeta 4, ff. 149–150).

Vanegas, I. (2011). Todas son iguales. Estudios sobre la democracia en Colombia. Bogotá, Colombia: Universidad Externado de Colombia.